A new report on sexual abuse in New Zealand says abuse in religious settings often causes “particular harm” to victims.

The report quoted Thomas Doyle, a former Catholic priest and a leading expert in abuse in the Catholic Church, who called it “soul murder.”

The report by the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care – titled He Purapura Ora, he Māra Tipu; from Redress to Puretumu — was tabled in New Zealand’s parliament on Dec. 15.

The document makes recommendations on how survivors of abuse in state and faith-based care should be listened to and how they should be compensated. The three religious denominations covered in the report were the Catholic Church, the Anglican Church, and the Salvation Army.

The Royal Commission was set up by the government but was completely independent from the government and the religious groups involved. The main period of investigation was 1950 to 1999, although it had the discretion to consider incidents from before and after this time period in order to inform its recommendations.

The report noted that survivors who experience religious or spiritual abuse “can have a shaken sense or complete loss of faith and spirituality – things that are sometimes central to the survivor’s sense of identity prior to the abuse.”

“They may stop participating in religious observances and practices all together. This can contribute to an intense sense of loss of the spiritual dimension of identity, which previously provided a source of strength, support and meaning,” the report said, adding the trauma of the abuse could cause victims to not be able to attend weddings, funerals, baptisms or other family gatherings if those events take place in a religious setting.

“The signs, symbols, rituals and persons that represented spiritual security become enduring reminders of the betrayal and trauma suffered,” the report notes.

The report said that prior to the 1990’s, Catholic Church leaders responded to reports of abuse in an ad hoc manner, usually under conditions of great secrecy. Few records were kept, and even when reports of abuse were documented in some way, records were often incomplete.

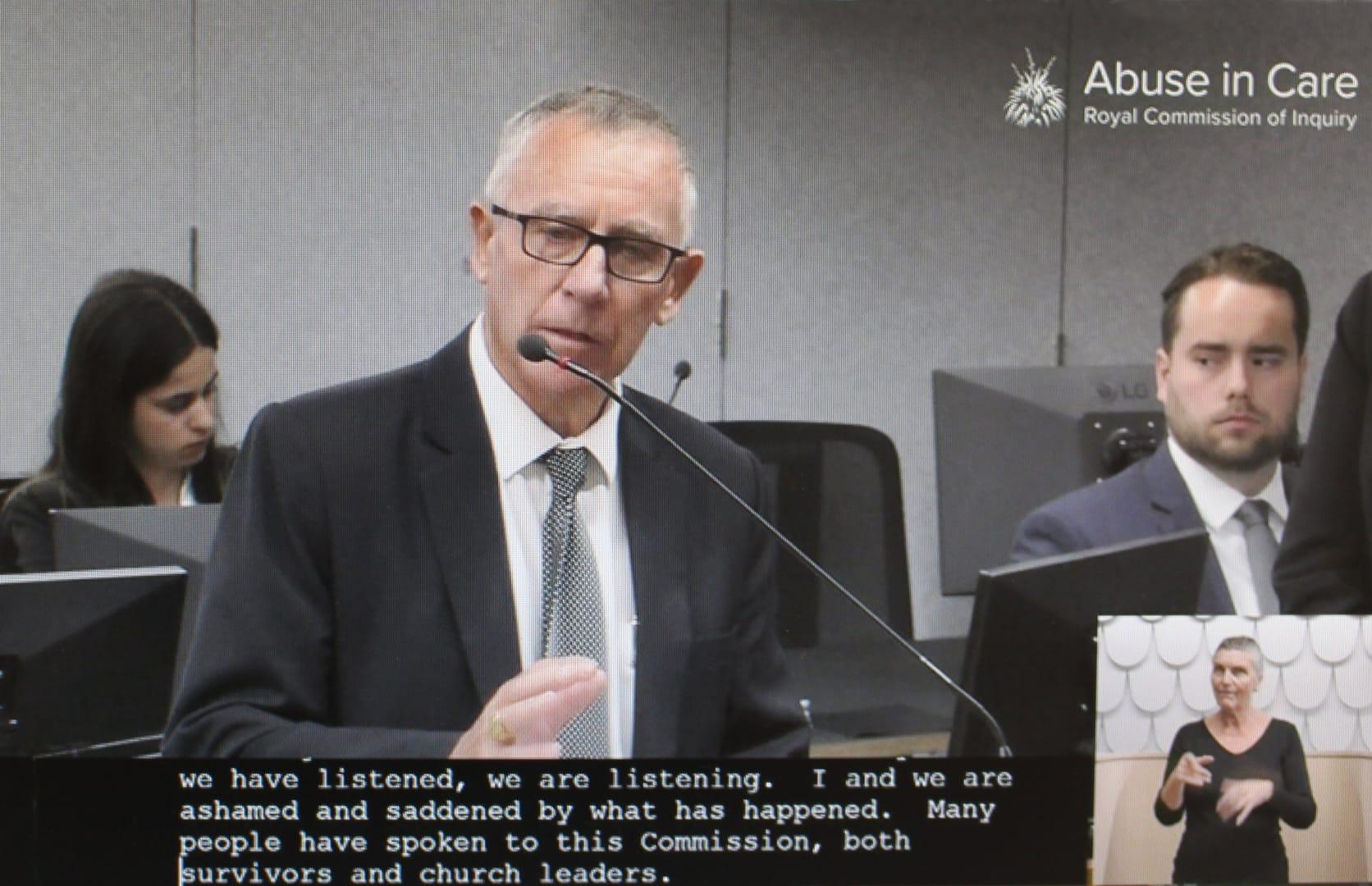

In his testimony to the inquiry, Cardinal John Dew of Wellington acknowledged the approach of the Catholic Church to redress and cases of abuse before 1985 was not well handled, saying “that was a terrible time and it should never ever have happened like that.”

The report claimed the Catholic Church “has not taken sufficient steps to reduce” the “numerous” structural barriers survivors face hen disclosing abuse to the Church, and added there have been failures by bishops and religious superiors to use procedures under Church law, or to use them properly.

“In addition, only the Holy See can permanently remove a priest or bishop from ministry, but responses from the Holy See are often delayed. This suggests the rights of alleged abusers being prioritized over survivor needs and over the prevention of further abuse,” the report said.

The report also claims more emphasis is placed by Church authorities on the investigation of abuse claims rather than “treating the survivor with empathy and compassion.”

“Survivors’ interests are not paramount in the Catholic Church’s redress policy or in its redress process generally,” the report says.

“Catholic institutions frequently fail to provide appropriate care and support for survivors during redress processes or criminal proceedings,” it continues, noting that prior to the inquiry, the Catholic church had generally not attempted to collect or analyze information about reports of abuse, including about the prevalence of abuse.

“Poor record-keeping, a culture of secrecy and an apparent lack of interest or inclination to understand the nature and extent of abuse has meant the church leaders had limited insight into systemic issues impacting the safety of those in its care,” it says.

“Leaders of Catholic Church authorities did not prioritize their duty to assess and minimize risk of further offending when responding to reports of abuse. We consider that they deemed redress processes and responses to survivors as separate to safeguarding responses. This ignores a key motivation of survivors to come forward which is to prevent further abuse,” the report continues.

The Crown Commission makes several recommendations, a public apology, streamlined communications and redress methods, and greater sensitivity to the cultural needs of New Zealand’s Māori and Pacific Islander communities.

The report was welcomed by the New Zealand Catholic Bishops Conference, the Congregational Leaders Conference of Aotearoa New Zealand representing Catholic religious orders and similar entities, and Te Rōpū Tautoko, the group formed to coordinate Catholic engagement with the royal commission.

“We have been listening closely to what survivors have been telling the royal commission. We have previously indicated our support for the establishment of an independent redress scheme. This report gives a series of recommendations we can study to help us as we walk alongside survivors of abuse,” Dew said in a Dec. 15 statement.

Follow Charles Collins on Twitter: @CharlesinRome