SÃO PAULO, Brazil – Catholic missionaries in Brazil are warning the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the numbers of vulnerable people subjected to forced labor.

The precarious situation of rural populations, migrants, and other susceptible members of society are leading many working in near-slavery conditions.

Tomoya Obokata, the United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on the contemporary forms of slavery, warned in May that “the severe socio-economic effect of the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to increase the scourge of modern-day slavery.”

In Brazil, the pandemic could throw 14.4 million people in poverty, according to a recent study led by researchers connected to the United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER). About 14 million Brazilians already live on less than $1.90 per day.

“We don’t have statistical data about this situation yet, but it has been a constant concern of the Brazilian episcopate. Despair may force people to accept dangerous work offers,” Bishop José Ionilton de Oliveira of Itacoatiara, in Amazonas State, told Crux.

Oliveira is the Vice-President of the Bishops’ Conference’s Land Pastoral Commission (CPT), which has monitored unfree labor in the country since the 1970s.

The Amazon region has been the epicenter of the scourge of modern slavery in Brazil. According to Sister Jean Ann Bellini, one of CPT’s national coordinators, the isolation in the rainforest favors the abuse of workers.

“When I lived in [the Amazonian State of] Mato Grosso, rural workers used to tell me how labor contractors took them to faraway regions in the rainforest. They were exploited there and couldn’t run away, because they didn’t know the area,” Bellini told Crux.

Illegal miners and loggers who invade reservation areas in the Amazon in order to conduct their operations usually exploit laborers.

“It’s all illegal with those initiatives, so workers don’t have a labor contract and are easily abused,” Oliveira said.

The bishop added that local farmers – particularly cattle ranchers and soy and sugarcane growers – also often exploit laborers.

“A person is taken to a distant region with the promise of a job, but then realizes that the wage is absurdly low and that lodging and food have to be paid by laborers – and are very expensive. So, the workers are always in debt and become prisoners,” he said.

Brazilian anti-slavery laws doesn’t just cover issues such as indebting workers, but also says degrading working conditions are analogous to slavery.

“This is usually the case in the Amazon. In the middle of the rainforest, for instance, workers most of the times have to drink water from a nearby dirty stream,” Bellini said.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic reached Brazil in March, environmental agencies in the Amazon cut down or even completely suspended inspections in the region. This has led to a surge of illegal logging and land clearing, and subsequently, deforestation.

“Apparently the same thing is happening with the labor monitoring. If no one is watching, those people take advantage of the situation to increase their income,” Bellini said.

The government budget for labor monitoring, Bellini said, has been gradually cut over the past few years, reaching a nadir in the conservative administration of President Jair Bolsonaro.

With the help of parishes and dioceses, CPT is trying to raise awareness on the risks of unfree labor during the pandemic, with social media posts and radio programming.

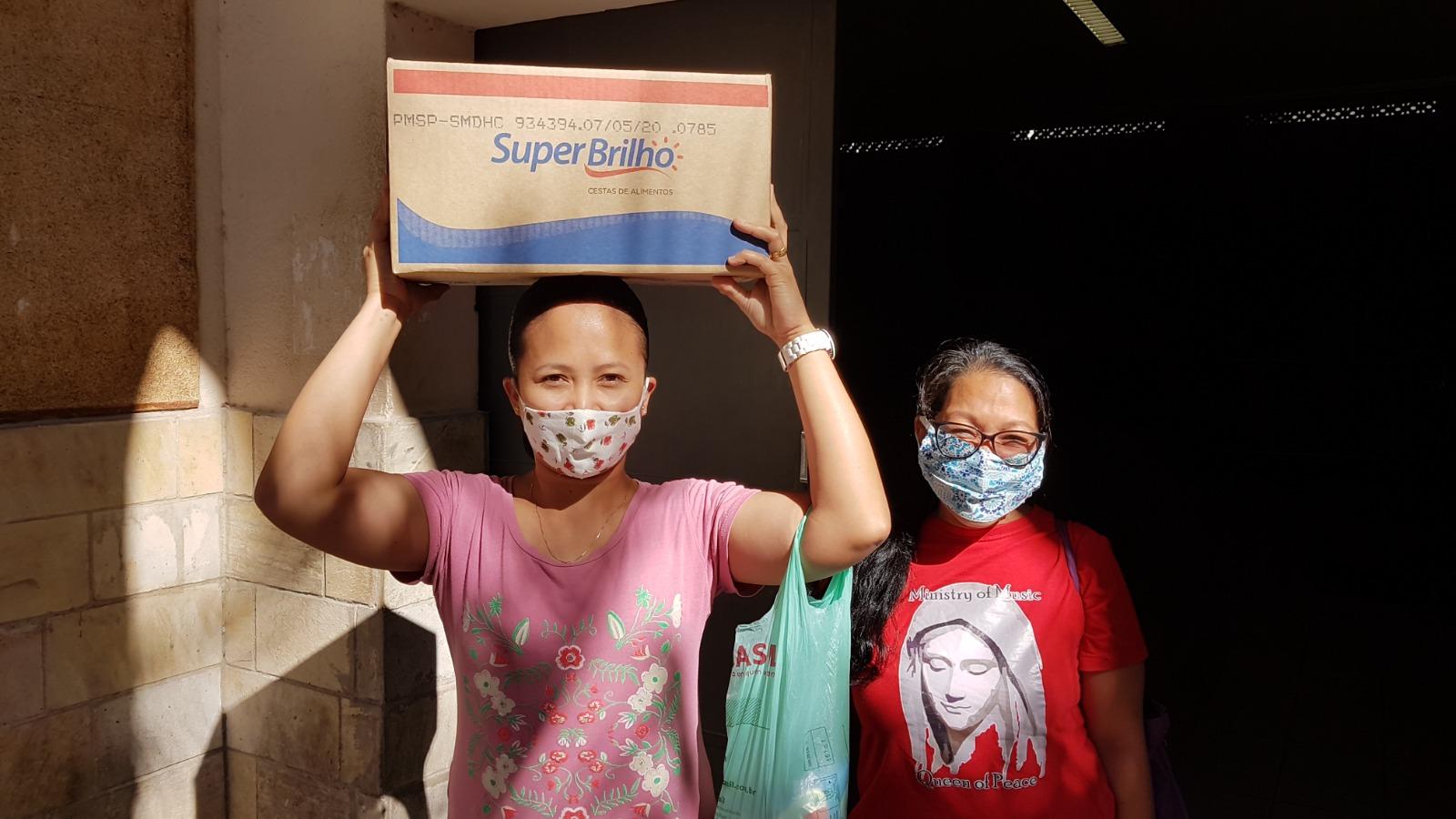

“The Church has also distributed food donations to thousands of families, so people will gain some time to think before accepting a risky job offer,” Oliveira said.

In urban areas, slavery-like conditions often involves undocumented immigrants coming from Bolivia, Paraguay, Haiti, Venezuela, and African countries.

In the city of Fortaleza, the Migrants Pastoral Service has been concerned with the situation of hundreds of African students who used to work in the tourism industry and now are unemployed due to the COVID-19 crisis.

“The Church has distributed food to hundreds of people and helped to secure the immigrants’ right to be paid an emergency aid by the federal government during the pandemic. But they’re very vulnerable right now and cases of slave labor may be happening without our knowledge,” said Gilvanda Torres, one of the national coordinators of the service.

In São Paulo, Scalabrini Father Paolo Parise, who coordinates the Missão Paz (Mission Peace) center for immigrants and refugees, told Crux about the how people are being exploited in the pandemic.

“Bolivian and Paraguayan immigrants usually work in sewing shops and most of them are closed now. So, many immigrants are starving – and very susceptible to abuse,” he said.

The novel coronavirus has strongly impacted those immigrant communities. Parise said that the number of prayer requests for deceased Bolivian and Paraguayan people in São Paulo during on-line Mass celebrations sometimes reaches 10 per liturgy. With the economic freeze, thousands of immigrants have been begging for food at his church.

“We’ve been helping at least 2,000 families in the last two months,” the priest said.

He said the mask-making industry that has mushroomed during the COVID-19 crisis in one area where immigrants are being exploited.

“We’ve been informed that buyers are paying only 2 cents per mask. People must cut the cloth and sew it up at home, using their own electricity. It’s a new form of hyper-exploitation,” Parise said.

“We buy face masks to be protected against the virus, but we don’t imagine how they were manufactured,” he added.

A darker side of forced labor in Brazil is the recruitment of people – usually women, many times underaged – to serve as prostitutes in places that are far away from their home cities.

Without an adequate monitoring system by the government during the pandemic, such cases are definitely rising now, said Sister Roselei Bertoldo.

The nun works for the A Cry for Life Network, an organization that helps the victims of human trafficking in Brazil.

“And all this is happening in an even more disguised way now,” she told Crux.