SÃO PAULO, Brazil – One year after the murder of Juan Antonio López, a lay Catholic and environmental activist in Honduras, the Latin American Church keeps asking for justice – and campaigning for the protection of other defenders of the common house who have a price on their heads.

López, who was 46 years old, was a critic of an iron oxide open-pit mine in the forest reservation of Botaderos and had been receiving threats. In October of 2023, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights had issued precautionary measures to protect him.

A city counselor in Tocoa, Colón department, he also opposed mayor Adán Fúnez, who always supported mining in the local natural reserves.

Fúnez had appeared on a video negotiating bribes with drug dealers days before López’s killing. Congressman Carlos Zelaya, brother-in-law of President Xiomara Castro, also appeared on the video. López had been demanding Fúnez’s resignation.

Father Noel Ortiz, executive secretary of the Mesoamerican Ecological Ecclesial Network (known by the Spanish acronym REMAM), told Crux that the preliminary hearing was postponed several times.

“The defendants’ lawyer looked for an express suit, without a trial. This way, only the three men accused of being directly responsible for the crime would be convicted and we wouldn’t know who the masterminds are,” said Ortiz.

The prosecutors didn’t accept such a petition and the suit will go on, now with the three defendants facing trial.

Although there’s reason to hope that justice will be served in López’s case, the slow pace of the process has been adding to the overall sensation of impunity that exists in the region when it comes to ecologists and human rights activists.

“At any moment another activist like Juan can be murdered. Only a couple of months ago, [Garifunas’ rights activist] Miriam Miranda publicly said that she has been continuously threatened and that she doesn’t want to die,” warned Ortiz.

López’s colleagues, who combat mining in the region of Tocoa, are among the most probable targets, the priest added.

The killing of Juan López was one of the major reasons why the Episcopal Conference of Latin America (known by the Spanish acronym CELAM) launched in December of 2024 the campaign La vida pende de un hilo (life hangs by a thread).

The idea was to bring visibility to the struggles of communities formed by peasants, traditional populations, and ecologists, promote the exchange of information and best practices among them, and have international impact in the denunciation of damages to the common house and to human groups.

“The campaign has reinforced the ties of REMAM, the Honduran Church and several grassroots movements connected to López,” Ortiz said.

According to Óscar Elizalde Prada, who heads CELAM’s communications center, the campaign has managed to successfully make visible the stories of different activists in the region.

“The biggest effort has been to identify emblematic cases and make their stories known by the international community,” he told Crux.

Elizalde thinks that the awareness of such a problem has been growing among Catholics in Latin America, but there’s still a long way to go.

“The campaign has echoed in the Catholic and secular media. But we still have to overcome the phase of making people sensitive about it and reach a real commitment to the defense of the people and of the environment,” he said.

Father Francisco Hernandez, who heads CELAM’s Center of Programs and Networks of Pastoral Action, told Crux that the most important achievement of the campaign has been to “make the threatened communities feel they’re not alone.”

“They have been accompanied by several organizations and by the Latin American Church. And those who thought that bringing death to them was the way are now equally aware they are not alone,” he said. “They may be powerful, but they noticed that our communities’ organization is also powerful.”

The risks are more real than ever, Hernandez said, “but there’s a growing consciousness among part of the Catholics concerning ecotheology and ecological spirituality.”

“And organizations like REMAM have been more and more fertile through the strength of its martyrs,” Hernandez added.

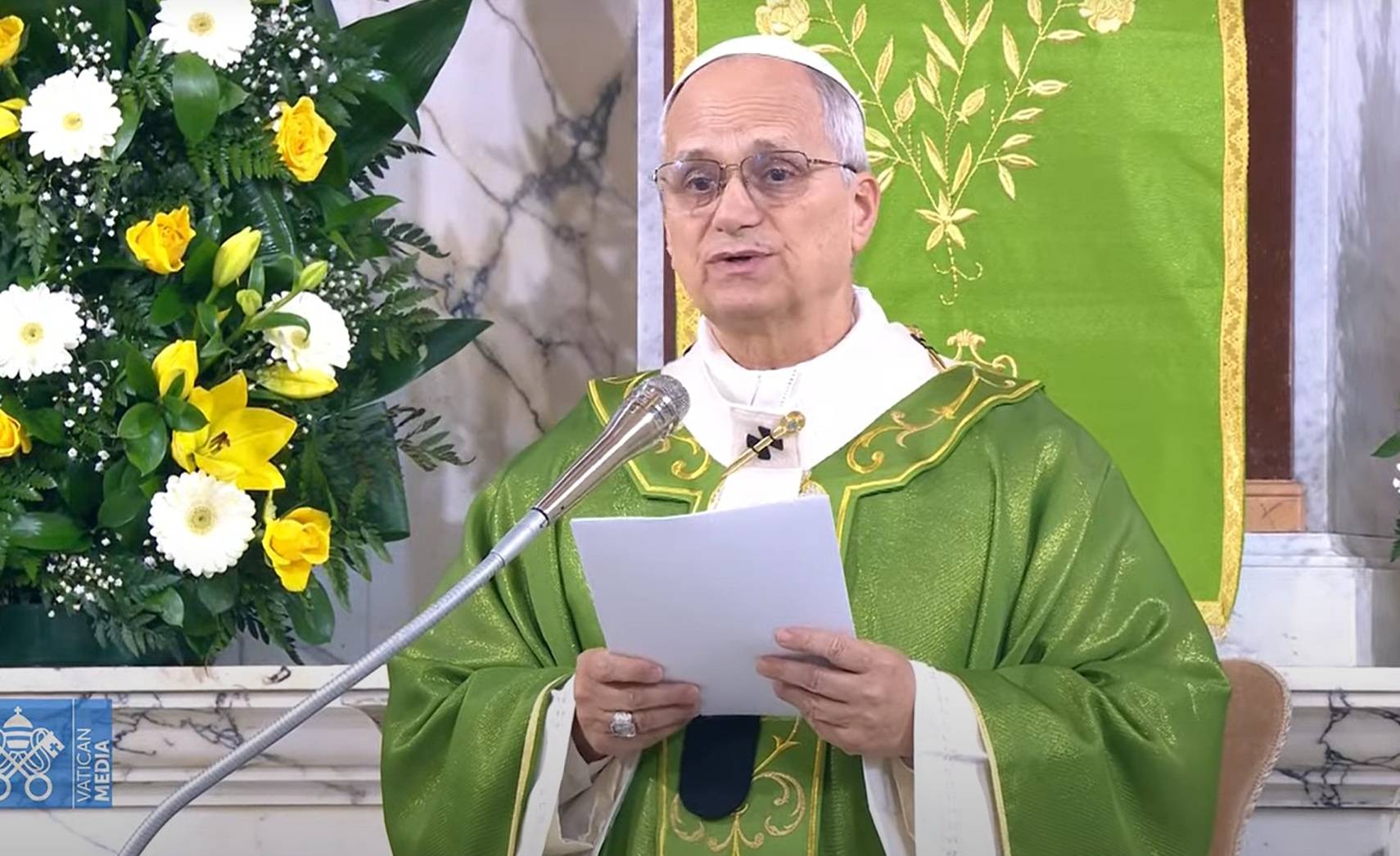

Father Noel Ortiz said that in May members of REMAM visited Pope Leo XIV and discussed with him the situation in the region, the risks, and their work.

“He told us that we must keep having a prophetic voice, like Juan had,” Ortiz said.

In his opinion, Juan López was able to “break up with an intimate form of religiousness and took his pastoral work to the streets, movements and organizations.”

“That would be the next step for many Catholics,” he declared.

That can be dangerous, of course. During a ceremony on Sept. 14 to commemorate the martyrs and witnesses of the faith in the 21st century, the pontiff mentioned U.S.-born Sister Dorothy Stang, who lived in the Brazilian Amazon for decades and fought for an ecological way of development in the region, especially for landless peasants. She ended up being killed by big landowners in 2005.

Leo XIV recalled that “when her attackers asked for her weapon, she showed them her Bible, calling it her only weapon,” said a Vatican News story.

Like López, Stang, murdered almost 20 years before him, has been continually recalled in the campaign La vida pende por un hilo.