A book recently released in Argentina shows two sides of Pope Francis equally unknown to the general public: those of an intimate friend and of a spiritual director.

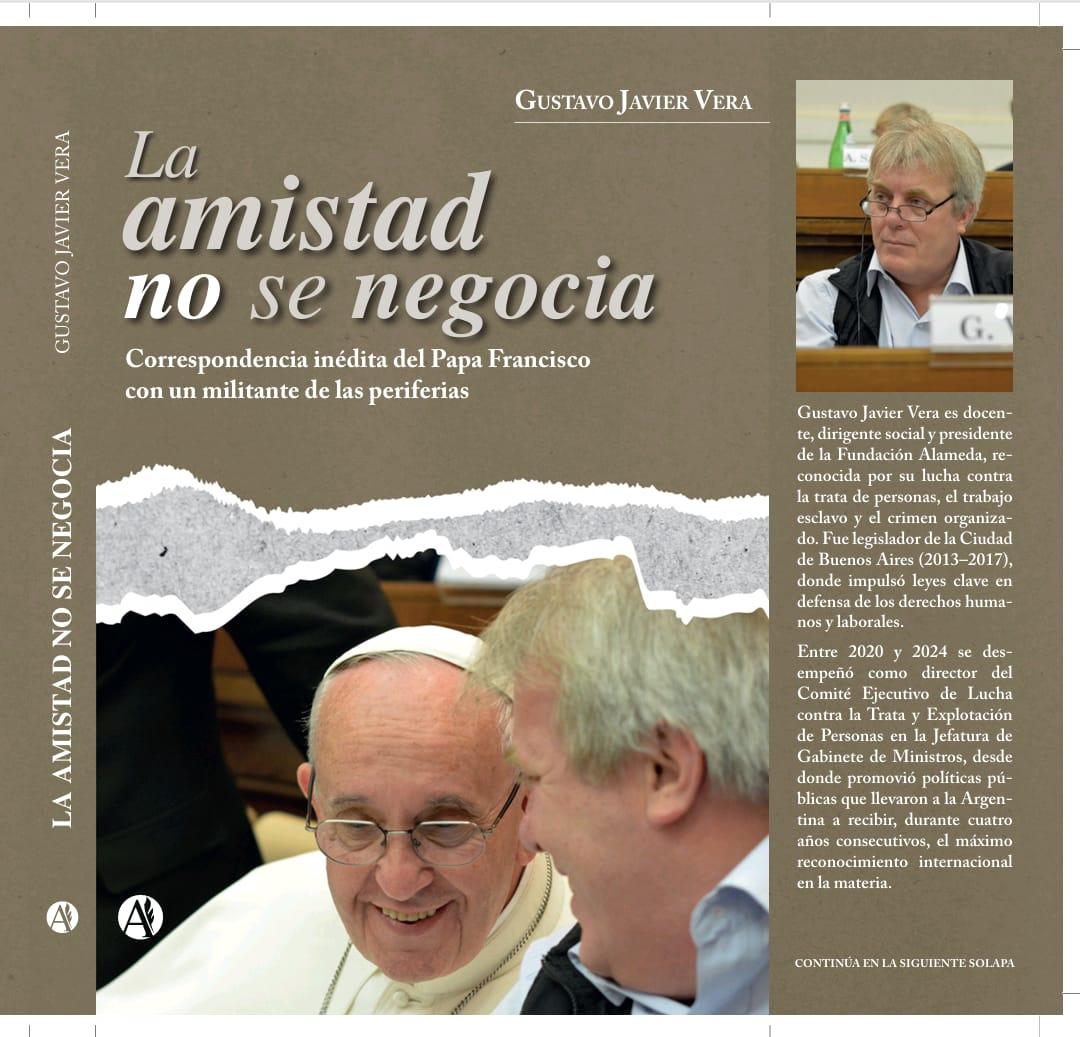

Authored by Gustavo Vera, a human rights activist and former city council member in Buenos Aires, La Amistad no se Negocia (Friendship is not Negotiable, 2025 Editorial Autores de Argentina) is based on letters Vera exchanged with Jorge Mario Bergoglio (first as an archbishop, then as pontiff) over 17 years of friendship.

The book tells the story of the unusual relationship between a high-ranking member of the clergy and a left-wing activist, and demonstrates how Bergoglio, little by little, touched Vera’s heart – not only with his wise words but also with his deeds.

Many chapters narrate how Bergoglio guided Vera on his faith journey – much of it a journey of recovery – while other parts present readers with Vera’s thoughts concerning different issues and problems. His loyalty and commitment to the relationship with a close friend is an omnipresent layer of the work.

“When I first met him, I was skeptical about an inward-looking Church. But as we saw how consistent he was, how his words matched his actions, we began to understand he was a very special man,” Vera told Crux.

With Catholic professor and social activist Juan Grabois and others, Vera is a founding member of La Alameda, an NGO specializing in human trafficking, work exploitation, modern slavery, and prostitution. They looked for Bergoglio when they learned that he was one of the few voices in society denouncing the exploitation of the poorest.

Bergoglio quickly agreed to collaborate with them. One month after their first talk, he celebrated a Mass in a poor neighborhood in honor of the victims of human trafficking and social exclusion.

A chapter describes how the then-archbishop had prepared a homily and brought it with him. But, as he got into the Church and saw all those poor people, with their faces of suffering and despair, he decided to talk to a few of them and listen to their stories. He ended up forgetting about the homily he had written and talking directly from his heart.

“He had such a connection with the poor. He would talk to them, give them a hug, be moved by them. Those things touched me deeply,” Vera recalled.

He was also surprised by Bergoglio’s austere lifestyle. As a cardinal, he chose to live in a common apartment and use the city’s public transportation system.

“And it was something authentic the way he would take a bus or visit a slum. He repudiated any kind of ostentation,” Vera said, recalling some of the proverbs Bergoglio would frequently use, like “The higher, the lower.”

“When your responsibilities grow, you must be more humble,” he interpreted.

The archbishop’s Masses against human trafficking and work exploitation between 2008-2012 were a central part of the NGO’s struggle. In that period, 1,200 brothels and 2,000 clandestine workshops were identified. A number of criminal organizations behind human trafficking – of which police agents were part – were dismantled.

Bergoglio visited La Alameda on different occasions and the ties with the group were strengthened. After some time, they became good friends.

When the NGO denounced a prostitution ring operating in properties that were owned by a Supreme Court justice (an ally of then-President Cristina Fernández), press outfits sympathetic with the elite establishment accused Bergoglio of being behind the “attack” and called Vera and his colleagues “God’s Trotskyists.”

After Bergoglio went to Rome and was elected Pope Francis, Vera would meet him a great many times during human rights events. A fundamental part of their friendship, however, was their epistolary correspondence. Writing to Jorge became a weekly ritual for Vera.

The book presents parts of many of such messages. In many of them, Vera would describe his battles against labor exploitation and pandering, linking them with Bible passages he was studying or on which he was meditating.

Francis would at times answer with only a few words and explain that he was busy preparing for a trip, for instance. But he would always include a reflection on the part of the Bible mentioned by his friend, approving his comprehension of it.

At times, the pope’s answers were lengthy and delved into the meanings of the Scripture, relating them to current events in Vera’s life, in Argentina, or in the world. They would discuss Judas Maccabeus, Hosea and the Book of Acts, among many others.

That was the dynamic in which the figure of the spiritual director appeared. Francis gave a Bible to Vera in 2014, and he would meticulously study it over the following years, continuously discussing his understanding with his mentor.

“Beautiful figure that of Job. I understand what you tell me about the moment La Alameda is facing in connection to Job. But for Job it was a time of consolation, don’t forget about it. And I’m sure you’re living that moment. It’s a time of fruitfulness,” the pope once commented in answer to a letter in which Vera had discussed some problems facing his NGO.

In another letter, Francis commented on Vera’s mention of a passage of the Book of Isaiah (43, 1-7):

“Isaiah’s text is profound. It could give us the impression that it’s a utopia, but it’s not: it’s a promise. When utopias are rooted in people’s history, as it is the case with Isaiah, they are a real hope for the future,” Bergoglio wrote, adding that he liked Vera’s understanding of it.

In 2017, when right-wing president Mauricio Macri was ruling Argentina and the sociopolitical atmosphere was not favorable for human rights activists, Vera sent Francis a long letter describing the situation in the country and mentioning a passage from Judith.

“The figure of Judith is inspiring for all human struggles. A woman of God, brave, realistic, and concrete. It gives me spiritual strength to read the Book of Judith,” Francis wrote in his answer on Aug. 20.

Vera would also talk to Pope Francis about his work in the Vatican and as an international leader. Before visits to other nations, he often gave information to Francis about the sociopolitical situation and his opinions about the most pressing issues.

On his end, Francis would comment here and there about his own battles, like the financial reform he promoted in the Vatican – a very tough moment for him, as Vera defined.

“Those were the hardest times of his pontificate,” he said.

Despite the challenges, in his meetings with the pope Vera would notice that he was very satisfied with his responsibilities and liked to do things his way.

“He went to Santa Marta because he just couldn’t be far from the real people. And the workers loved him and would take much care of him,” he added.

Once, the two of them were having dinner when a Vatican worker came near Francis and whispered something in his ear. The pope laughed and told Vera: “He said a cardinal is arriving and that he’s walking. He left his luxury car far from here. He’s only walking to pretend that he’s a simple man.”

The book deals with all the great themes of Francis’s reign: inter-faith dialogue, the protection of our common home, child abuse in the Church, Argentine politics.

“He would never avoid troublesome issues. He got into every kind of trouble,” Vera said. To hear Vera tell it, Francis was always trying to build bridges in order to create the conditions for progress, especially when it comes to themes of war and peace, of environmental protection, and human rights.

In the middle of all that, he would never forget to send a letter to his friend for his birthday, to talk about Vera’s mother’s health, to make fun about soccer and to tell jokes.

“He would remember details about me years later and mention them. Some of those things surprised me and moved me. Friendship for him was something very serious,” Vera recalled.

Writing the book was a way of grieving the loss of a friend, Vera said.

“His presence was enormous in my life,” he concluded.