Walk into pretty much any grocery store in America and ask for Land O’Lakes, and you’ll be directed to a brand of butter. Walk onto any Catholic university campus in America and ask about Land O’Lakes, and you’ll get an entirely different sense of what it’s all about.

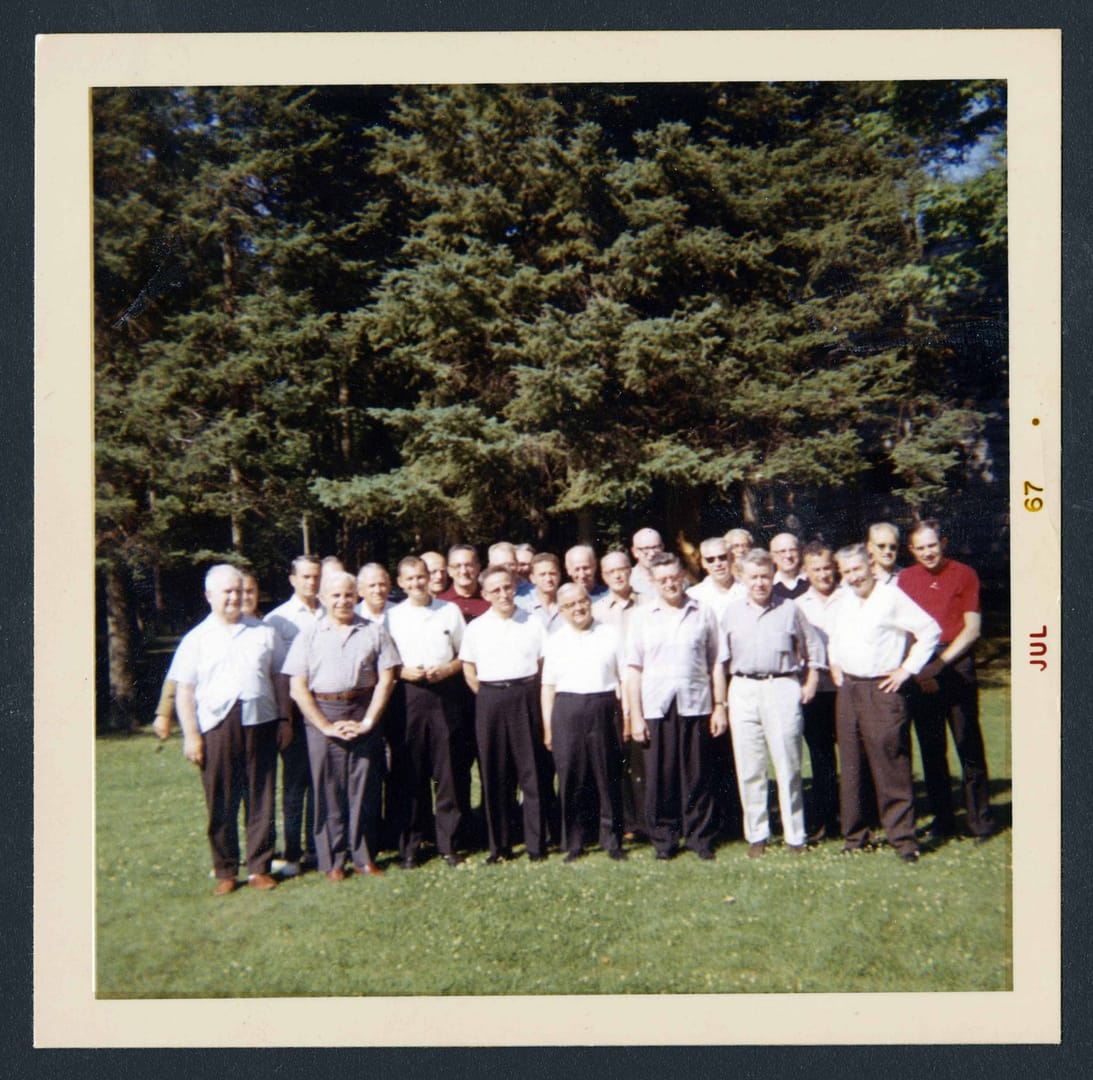

Fifty years ago this year, a group led by Father Theodore Hesburgh, president of Notre Dame, and Father Paul Reinert, president of Saint Louis University, gathered in July in Wisconsin to reflect on the direction of Catholic higher education in the country. At the end they issued a document, which is technically called a “Statement on the Nature of the Contemporary Catholic University.”

By fans and detractors alike, however, it was immediately dubbed the “Land O’Lakes Statement,” and the name has stuck.

These were the heady days of the immediate post-Vatican II period, and the statement was widely seen as a declaration of independence for Catholic universities.

While hardly cutting ties with the institutional Church, the statement asserted that universities must be free to pursue the highest standards of educational excellence, which include academic freedom, open discussion, and the ability to raise critical questions, and foresaw an only indirect role for ecclesiastical governance.

Ever since, Land O’Lakes has been a banner of pride for some, but the beginning of the end for others, a trigger that set off a progressive erosion of universities’ Catholic identity.

During a recent conference on the statement, historian John T. McGreevy insisted that despite everything, Land O’Lakes has “aged well.”

“The optimism of the authors was buoyant but not naïve, focused on engagement as a theological and practical strategy, not a capitulation to the world,” he said.

He cited a recent article by Notre Dame’s president and a successor of Hesburgh, Father John Jenkins, who said that Land O’Lakes expresses in terms of a university “the desirability of a Church acting in the world, as opposed to a sect withdrawing from it.”

As a humorous footnote, Mc Greevey said that given the setting, it’s sort of surprising anything at all resulted from the gathering.

Land O’Lakes had “no air conditioning” in the summer of 1967, McGreevey said, and was best known as a place “to do research on mosquitoes,” so it was “a wonder anybody came!”

The event at which McGreevy spoke was sponsored by Notre Dame’s Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism in collaboration with the Office of the President. His talk was followed by a panel discussion with five Catholic university presidents: Father John Jenkins of Notre Dame, Father William Leahy of Boston College, Patricia McGuire of Trinity Washington University, Father Joseph McShane of Fordham University, and Julie Sullivan of the University of St. Thomas.

Others, however, aren’t quite so sanguine about the document’s impact.

In an interview with Crux earlier in July, John Garvey, president of Catholic University of America, talked about the Land O’Lakes anniversary and pointed out that Hesburgh was actually a graduate of Catholic U.

Garvey said that fifty years later, the vision behind Land O’Lakes is a mixed bag.

“One of the things they said is that to be truly Catholic, you need academic freedom from any sort of influence, lay or clerical,” he said. “This is not the view of Lumen Gentium, it’s not the view of Ex Cordae Ecclesiae, it’s not the view of John Paul II, or Benedict, or Francis.

“We provide an opportunity for the rest of the Church to think about the intellectual life of the Church at our university. But we are fighting a popular culture in trying to accomplish that,” Garvey said, and a strong bond between a university and the Church is essential.

In his own talk, McGreevy disputed the claim that the “authors understood a diminishment of Catholic identity as a necessary step to compete with, or mindlessly imitate” secular institutions.

The authors did want to stop “clumsy and inappropriate attempts at ecclesiastical control,” McGreevy said, but they also clearly wanted “Catholicism perceptively present” in their universities.

The real target of the Land O’Lakes statement, McGreevey suggested, wasn’t too much control by the Church, but too little commitment to excellence.

The authors, he said, were concerned their universities were going to be abandoned by the best and brightest students and professors. They were not getting the best awards and fellowships, there were no Catholic universities ranked in the upper tier of reputations of graduate programs, and their salaries were low.

“Mediocrity, then, not secularization” was the obstacle they believed they were facing, he said. “Hesburgh and Reinert wanted to change all that, and it’s clear that they were successful.”

McGreevy said that while “the strongest criticisms are reasonable,” he continues, “I did not say they are convincing. Land O’Lakes insists that Catholic institutions must engage the world, and this larger sense of engagement also underpins Gaudium et spes.”

He also said the document’s advocacy of engaging with the global south, or “Third World,” helped make Catholic institutions even “more self-consciously global.”