NEW YORK — A suggestion, not so much for young viewers, but for the adults who may take them to the documentary “The Biggest Little Farm” (Neon): Don’t get too attached to any cute animal that has been given a name.

The movie’s focus is on organic farming — specifically, biodynamic farming, in which the soil is continually replenished without the use of chemical fertilizers and crops are grown without artificial pesticides.

The filmmaker is John Chester, an ex-wildlife photographer. Together with his wife Molly, a former culinary blogger and private chef, he owns and runs the film’s setting, Apricot Lane Farms, a picture-perfect 200-acre spread north of Los Angeles.

“The Biggest Little Farm” opened in theaters in May and will continue its run throughout the summer.

Made over an eight-year period that included the birth of son Beauden, now 4, it’s filled with poetic moments that are the dream of any parent taking a child on a farm tour. Kids will likely take it all in stride. Adults who catch on to the movie’s unforced and graceful emotional manipulation, however, could tear up a little.

The film takes the life cycle seriously and without sentiment — and that applies to people as well as farm animals and predators. Creatures are born, they die; crops sometimes fail; and coyotes who attack the chicken house are only some of the pests with which the Chesters must contend.

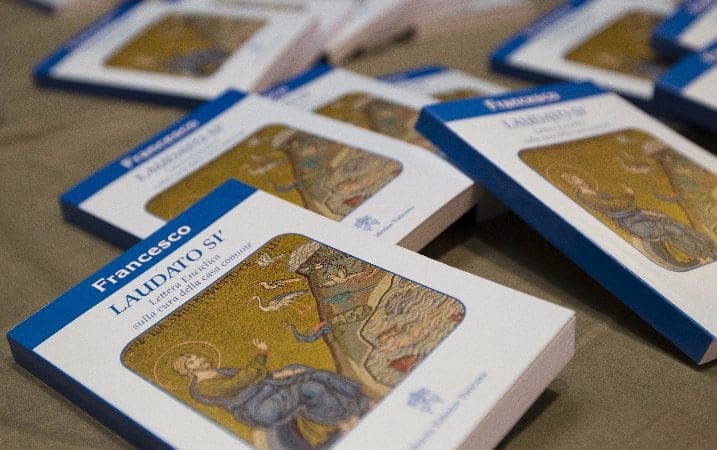

John Chester told Catholic News Service, “I tried to make a very simple film for children to see the value of biodiversity and topsoil.” But some Catholic bloggers also have seen his work as a useful exemplar of the values promoted in Pope Francis’s 2015 encyclical, Laudato Si’, on “Care for Our Common Home.”

Author Lisa Hendey, founder and editor of the website CatholicMom.com, wrote that the film reminded her of one passage in particular: “If we approach nature and the environment without … openness to awe and wonder, if we no longer speak the language of fraternity and beauty in our relationship with the world, our attitude will be that of masters, consumers, ruthless exploiters, unable to set limits on their immediate needs.”

“By contrast, if we feel intimately united with all that exists, then sobriety and care will well up spontaneously.”

On his blog, Tomas Insua, executive director of the Global Catholic Climate Movement, called the movie “a teaching tool for matters of both faith and reason and the relationship between the two. … And it reminds us,” he adds, “that sin is a reality in this fallen world.”

Told of that, Chester falls silent for a moment. “I think nature, you know, is a very literal reflection back to the deeper threats of the human condition.”

The farm operates with a staff of more than 60, including volunteers. The film also is a celebration of the virtue of grinding, repetitive tasks that have defined tilling the soil for millennia. “It gives purpose to the tediousness — because there’s a moral compass to how you work with nature,” Chester says.

The couple’s first success was with organic eggs, followed by varieties of stone fruit — apricots, peaches and plums. They currently grow 250 varieties of crops.

Chester also pays careful attention to their pet dog, Todd, a rooster they named Greasy and a lamb left orphaned when its mother died. Initially rejected by the rest of the flock, the lamb had to find a way to receive nourishment and survive.

“It’s the feeling you get when you lose someone important to you,” Chester explains. “As farmers, we have to rely on the resilience of life a little bit, even though it looks cruel. The lamb had to have the right level of tenacity to want to live.”

“Caring for ecosystems demands farsightedness, since no one looking for quick and easy profit is truly interested in their preservation,” Laudato Si’ states.

That’s the perfect definition of biodynamic farming, which requires a constant level of problem-solving that doesn’t involve chemical solutions. Invasive snails turn out to be ideal snacks for ducks. Duck droppings become fertilizer for the fruit trees. Starlings that peck away at the ripe fruit attract hawks.

Coyotes became the toughest obstacle to overcome. Chester didn’t want to resort to shooting them, but found it was sometimes necessary; “How do I justify letting 300 chickens die because I don’t want to shoot one coyote?”

And even the Great Pyrenees dogs, known as Pyrs, he brought in to chase away coyotes are no guarantee. “You have to find the right one who doesn’t develop a taste for chicken. There’s no way to know that they won’t. You just have to keep trying.”

“We are part of nature, included in it and thus in constant interaction with it,” Pope Francis wrote in Laudato Si’. Chester’s documentary only hints at the potential difficulties inherent in that interaction, which at one point include a threat from a wildfire.

“I always thought I’d become bored with farming,” Chester says. “But if you’re not dealing with the tedious tasks, you’ll end up with something you can’t fix without chemicals.” His film’s happy conclusion demonstrates that living in harmony with nature is very much within everyone’s reach.

– – –

Jensen is a guest reviewer for Catholic News Service.

Crux is dedicated to smart, wired and independent reporting on the Vatican and worldwide Catholic Church. That kind of reporting doesn’t come cheap, and we need your support. You can help Crux by giving a small amount monthly, or with a onetime gift. Please remember, Crux is a for-profit organization, so contributions are not tax-deductible.