WASHINGTON, D.C. — “It’s DACA; it’s good.”

Those were the words Giovana Oaxaca wrote to her staff, hands trembling, when she heard the Supreme Court ruled in favor of recipients of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA.

“I prayed for this moment for you and your brother and here we are,” was the only sentence the 23-year-old DACA recipient’s mother could muster in between tears, as the two rejoiced in this small victory in a battle that is far from over.

On June 18, the U.S. Supreme Court in a 5-4 ruling said President Donald Trump could not stop the program with his 2017 executive order. DACA protects about 700,000 young people who qualify for the program from deportation and allows them to work, go to college, get health insurance and obtain a driver’s license.

The program was established by President Barrack Obama with an executive order in 2012 to allow young people brought into the country illegally as minors by their parents to stay in the United States.

Oaxaca works for the Catholic social justice lobby Network as a government relations associate. Part of her job is being an activist and advocate for immigrant rights.

“I was filled with, I use this word not lightly but, trepidation because every sign pointed to the decision being unfavorably toward DACA,” said Oaxaca in an interview with the Catholic News Service.

“I grew up thinking that I was going to have DACA for an uncertain amount of time and there would be a solution eventually,” she continued. “And when this administration came around in 2016, all of those hopes were immediately whisked away.

“Because that’s what the administration ran on, and that’s what the administration had been proposing — an end to DACA. So, for several years now, I’ve felt this lack of support, lack of acknowledgment that there is a need for a solution here,” she continued.

Though the June 18 decision was favorable, Oaxaca believes the U.S. immigration system as a whole is not.

“If the Supreme Court had elected to allow the administration to go through with ending DACA, there’s a very real possibility that I would not have been unable to renew my DACA on time, and I would not have been able to work legally in the country,” she explained. “And that’s in the midst of an economic and public health crisis.”

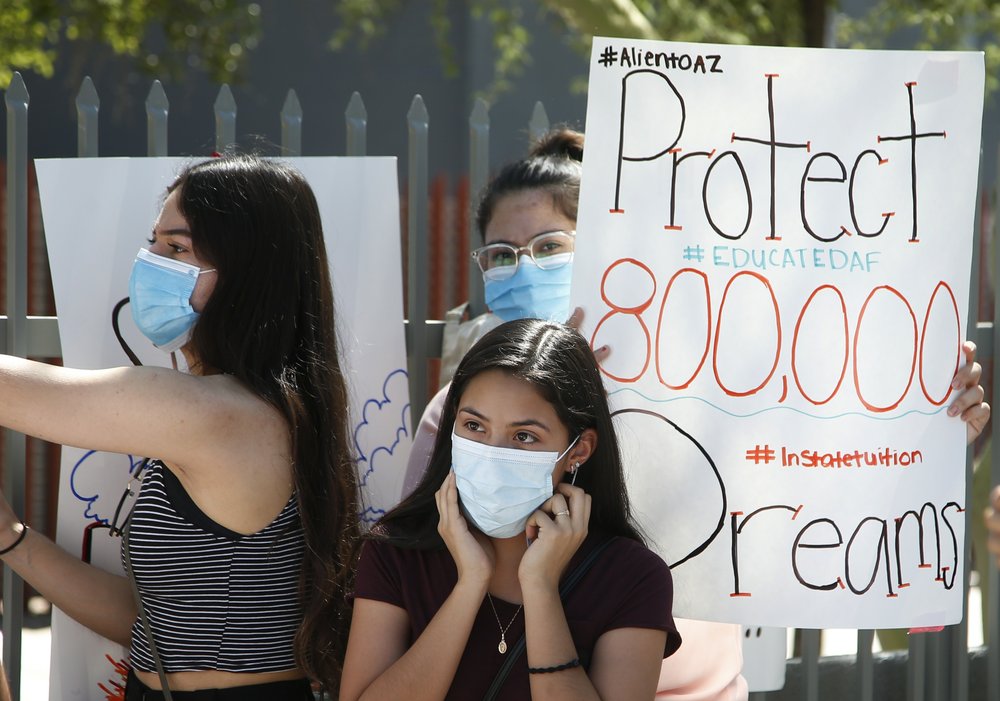

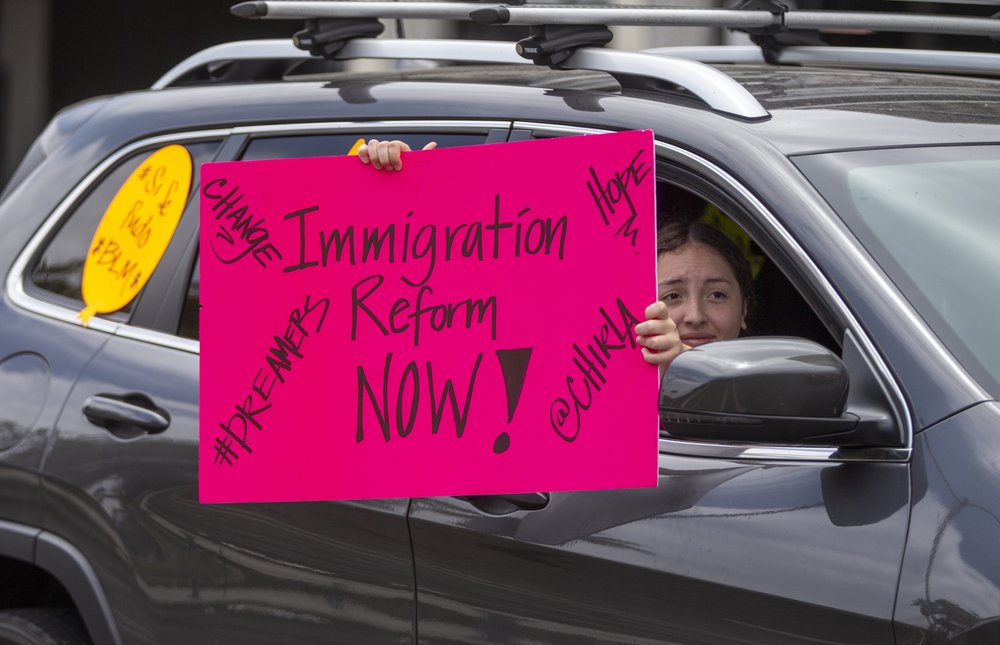

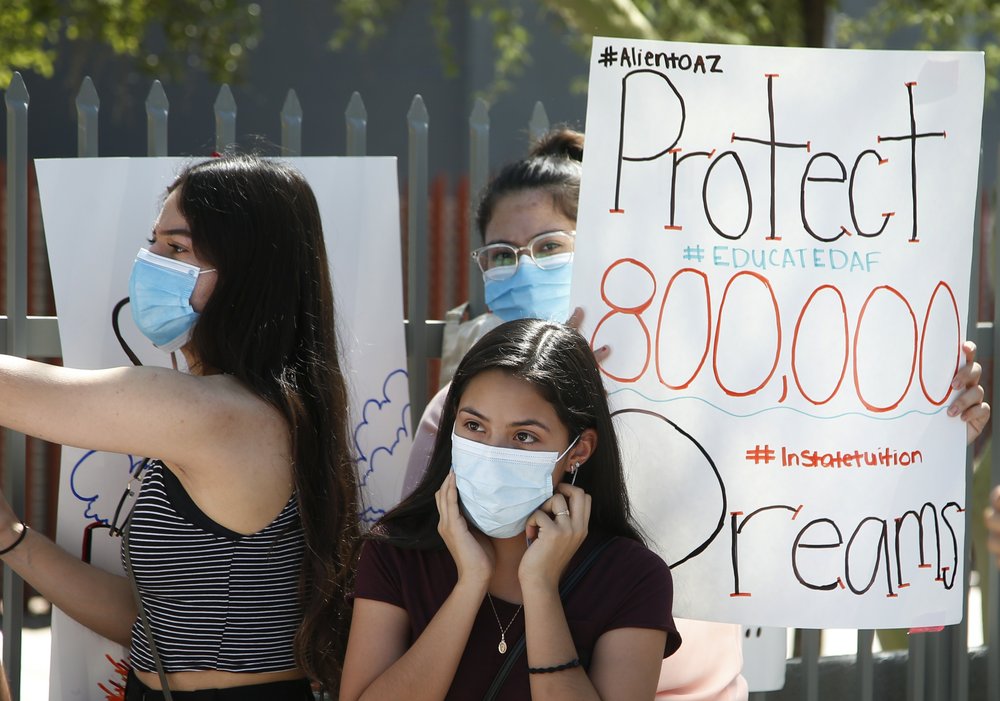

This is the reality for many DACA recipients and their families. Oaxaca and activists like her have worked for years to create a permanent solution for “Dreamers.”

Congress has considered the proposed Development, Relief and Education for Alien Minors Act, or DREAM Act, which would grant temporary conditional residency to these young people. First introduced in 2001, it has yet to pass.

“I think it shows that we’ve taken DACA nearly as far as you can go, and we’ve done everything we can as organizers, as immigrant rights activists and advocates, to show that a program like DACA needs to exist with full protections, meaning pathway to citizenship eventually being made available,” said Oaxaca, reiterating her commitment to fighting for immigrant rights.

“Dreamer” Claudia Quinonez, a recent graduate of Trinity Washington University in the District of Columbia and also a DACA recipient, came to the United States in 2011 from Bolivia with her mother.

“We came together fleeing political instability and climate change. My mother wanted me to have a better life, better education (and) better opportunities,” she told CNS.

“I’ve been going since Monday to the Supreme Court with a group of young people, and as we were walking to the Supreme Court at 10 a.m. together and waiting for the decision (on June 18), we got a text message saying that the decision had come out and we didn’t know what it was,” Quinonez explained. “Later on, we found out that we had a favorable decision.”

Quinonez attributes all that she has accomplished to DACA. Without the Social Security card that has enabled her to enroll in school, get a driver’s license and find work, she would have no place in this country to exert her ambition.

“I feel like ever since DACA was rescinded in 2017, I’ve been living under so much uncertainty,” said Quinonez. “We don’t know the exact details of what this decision means, but I have a feeling that I will be able to plan ahead and look forward. And not just exist but continue to live.”

In 2017, when Trump issued the executive order, the administration stopped considering new applications for DACA but allowed current DACA recipients with a permit set to expire before March 5, 2018, the opportunity to apply for a two-year renewal if they applied by Oct. 5, 2018.

Because various lawsuits were filed to challenge the executive order, and injunction was put on Trump’s plan until the suits made their way through the courts, with the case finally ending up at the Supreme Court. The court agreed to hear the case in June 2019.

“Growing up as a DACA recipient or as an immigrant in general, you don’t really know what to expect,” said Tania Hernandez-Orozco, a nursing student at Delaware University and a TheDream.US scholar, said. “You just listen to the news and pray that your family isn’t the next to get separated.”

This fear for Hernandez-Orozco has been fellow TheDream.US scholar Christian Aguirre’s reality.

Around March 2017, Aguirre was separated from his mother. After she was diagnosed with dementia, he and his family made the difficult decision for her to move back to Guadalajara, Mexico, where she could get the care she needed from their family.

At the time, Aguirre thought he could visit her in a few short months. However, in September 2017, DACA was rescinded and he has not seen his mother since; he could not leave the U.S. and expect to come back in.

Like his peers, Aguirre feels a sense of relief from the Supreme Court ruling, but he knows the fight is far from over.

Citizenship is the only thing that will end the uncertainty for DACA recipients and guarantee the security that many others take for granted, as well as the privilege to travel, so in Aguirre’s case, he could go see his mother.

“Before DACA, I was undocumented, so it was always unsure. With DACA, at least I had an opportunity to kind of pretend like I was a part of society, but the last two years I was reminded of the harsh reality that it is not a permanent fix,” said Jose Arnulfo Cabrera, the director of education and advocacy for migration with Ignatian Solidarity Network.

“What we have been advocating, what we have been talking about, is just that. This was not intended to be a permanent solution,” he said. “This is not the end game and we have been for the last few years and continue today to fight for a pathway to citizenship.”

“My family and I were open to getting bad news. We were like, OK, we’re not sure if they’re going to continue the DACA program, but whatever it is, God is in control,” said Ewaoluwa Ogundana.

Born in Nigeria and currently studying at Trinity Washington University, Ogundana explained her fear was more for her brother, who may not have the same opportunities DACA and the TheDream.US scholarship have given her.

“When I got the notification, I quickly opened it and I screamed, ‘Oh my gosh!’ It’s such an answer to a prayer,” she exclaimed, relieved to have been given more time to fight for the right to become a U.S. citizen.