WASHINGTON, D.C. — Catholics are taught there is one God in three persons. But in the world of memes — roughly described as photo- or illustration-driven editorial cartoons — there’s more than one Jesus.

For instance, there’s Storybook Jesus, delivering teaching to old and young alike in a pastoral outdoor setting. There’s Buddy Jesus, with a wide grin and a thumbs-up posture. And, in the combustible mix of religion and politics, there’s Republican Jesus, whose memes tend to have a generous dollop of the color red in them.

Memes are created to drive home the point that religious believers and politicians’ stances on matters of faith and public policy aren’t always consistently applied, according to Heidi Campbell, a professor of communication and a Presidential Impact Fellow at Texas A&M University.

“Most of what I saw (in memes) was very playful” as late as 2018, Campbell said in an Oct. 21 talk sponsored by Seton Hall University. “I’ve seen a shift in the last three years … partially because of the ethos that we’re living in,” with memes becoming more negative, she added.

“Some people have even employed meme-makers as part of their campaign strategy,” said Campbell in her talk, “Internet Memes and American Civil Religion.” It kicked off the Oct. 21-23 symposium “Communication & Religion in the 2020 U.S. Presidential Election” sponsored by Seton Hall’s Institute for Communication and Religion.

“You spend $500 million on advertising” as happened in the 2016 presidential campaign, Campbell said, yet the ad rollout can be upended by a meme that skewers one of the candidates.

Memes are common on social media. They have multiple roles, according to Campbell: As a framing narrative, a new digital language or genre, a form of digital storytelling with “multilayered storytellers,” and “visual and emotive forms of online communication employing popular culture images with succinct messages to communicate common beliefs.”

Not all memes achieve their intended effect. Campbell cited Israeli communications specialist Limor Shifman, who said in 2013, “Only memes suited to their sociocultural environment spread successfully, while others become extinct.”

Apart from the creeds of individual denominations is civil religion, which Campbell said is “presented as the dominant frame and the dominant belief system of the American people.”

Campbell told of how memes take note of “the politicization of religion,” which she defined as “the necessary outflow of a specific religious belief or set of religious values” which “centers on religious belief and claims to be the logical in relation to a specific partisan action.”

Turn that definition around and you have “the religiofication of politics,” which has also become part of the U.S. political scene, she added.

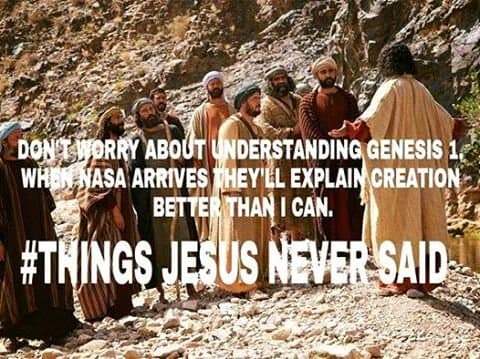

Memes skewer civil religion, according to Campbell. Jesus is used to “highlight the contradictions of Christianity,” and images of President Donald Trump with Jesus are used to demonstrate both true Christianity and fake Christianity.

Other characters in popular culture get words put into their mouth in memes for the sake of getting to the character’s catch phrase. Two examples used by Campbell included Dana Carvey’s “Church Lady” character from “Saturday Night Live,” and a Gene Wilder photo that Campbell called “Condescending Willy Wonka.”

People use memes “to critique and challenge … to make fun of inconsistencies,” Campbell said. But “negative mocking is the normative discourse and the dominant genre, unfortunately.”

Asked whether memes have the capacity to change people’s minds or simply reinforce beliefs already held, Campbell said, “These memes seem to be creating a kind of echo chamber,” but added that focus groups would need to be conducted to test such a hypothesis.

Another question posed was what difference memes make if they’re meant to appeal to a younger demographic — which also is the age group least likely to vote. “The upper end of Generation Z is 23” years of age, Campbell replied. “This might be the first election they’ve been able to vote in.”