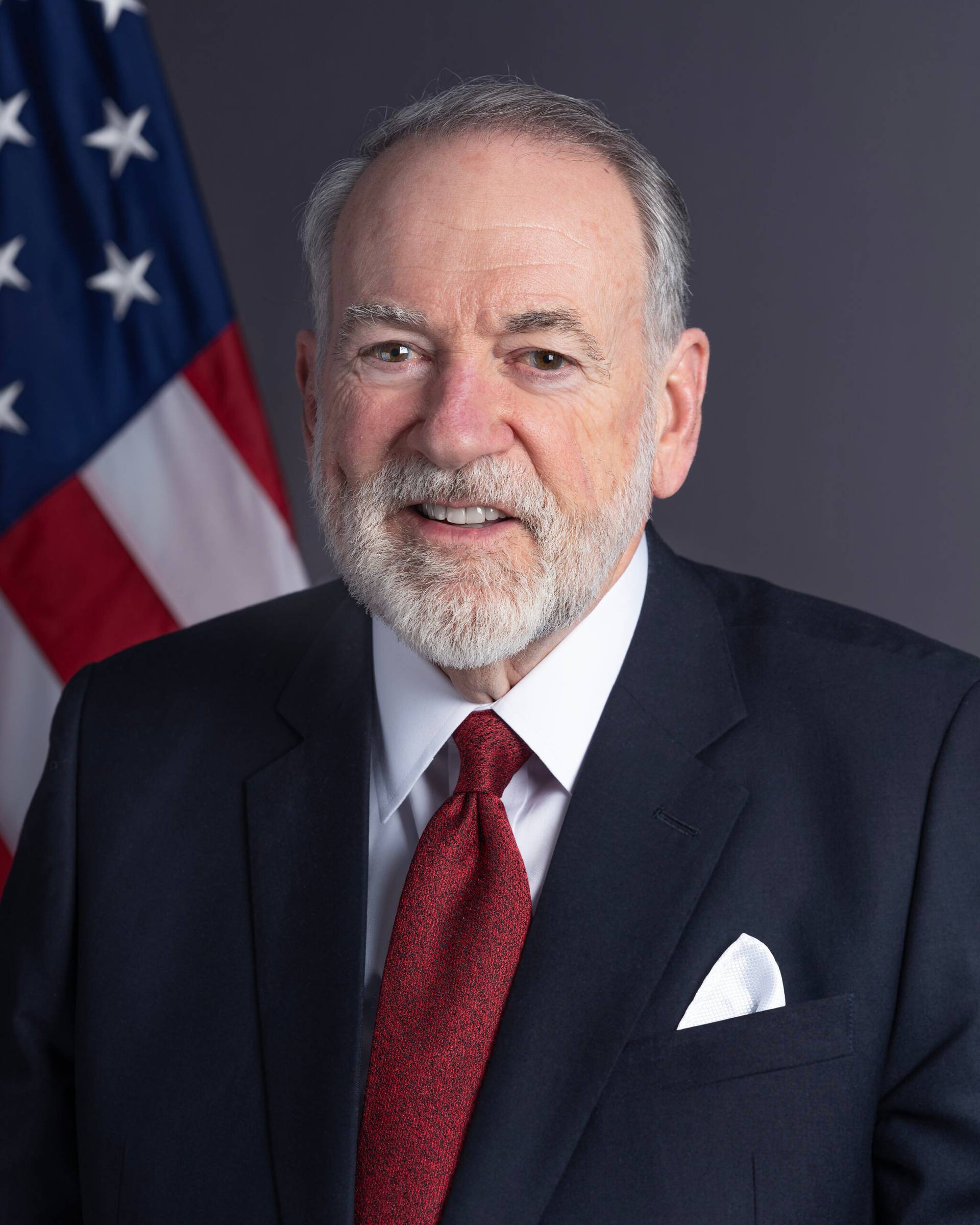

BLUE POINT, New York — Father Kevin M. Smith, a veteran fire chaplain, trauma counselor and loyal friend to scores of active and retired firefighters in the New York metropolitan area, receives more phone calls in early September than any other time of the year.

Most of the calls are from firefighters who served amid the carnage and chaos in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on New York City’s World Trade Center.

A fire chaplain with 30 years of service, Smith, 60, is commissioned by Nassau County, New York, to minister to members of the county’s 71 volunteer fire departments, many of whom work full time with the New York Fire Department.

He also is a member of the county’s Critical Incident Stress Management team, which provides support to firefighters and emergency medical services workers who are dealing with trauma associated with their duties as first responders.

Smith’s cellphone starts ringing and dinging with calls and texts from firefighters in the days leading up to and including the 9/11 anniversary. They come from front-line heroes who have been emotionally and, in many cases, physically affected by the cataclysmic event.

Smith — pastor of Our Lady of the Snow Church in Blue Point in the Diocese of Rockville Centre — can empathize with the callers. He, too, was a first responder at ground zero, arriving near the scene as the World Trade Center’s North Tower was collapsing, completing the total destruction of the two 110-story buildings and resulting in a mountain of crushed concrete, twisted steel and pulverized debris where they once stood in lower Manhattan.

In an interview with Catholic News Service to mark the 20th anniversary of the terrorist attacks in New York, Washington and Pennsylvania, Father Smith spoke about his role as a chaplain on and after 9/11.

“I can’t believe it was 20 years ago,” he remarked. “There are days when it feels like yesterday.”

For Smith, Sept. 11, 2001, began at St. Rose of Lima Church in Massapequa, some 40 miles east of the city. An associate pastor at the time, he had been preparing to celebrate morning Mass when a parish secretary told him to turn on the television where he witnessed the second of two hijacked jetliners crash into the World Trade Center.

Several minutes later, his fire pager chirped, alerting him about the mass casualty incident.

After notifying his pastor that he was responding to the call, Smith jumped into his black Chevy Trailblazer — a vehicle with emergency lights and sirens — and headed toward the city. Along the way he picked up his younger brother, Patrick Smith, an off-duty New York City firefighter, and dropped him off at his firehouse in the Bronx.

When he eventually arrived in lower Manhattan, Father Smith encountered a surreal scene. The devastation was overwhelming.

“The whole place was filled with smoke,” he recalled. “There was a lot of stuff coming out of the air. Fire trucks and Emergency Service Unit vehicles were catching fire from the falling debris and exploding.”

Throughout the day and into the early hours the following day, Smith — protected by a fire helmet and bunker coat — offered prayers, emotional support and assistance to firefighters and other emergency personnel. A trained firefighter, he also helped search for victims.

As shaken first responders went about their business amid the mayhem, a number of them asked Smith to hear their confessions.

“They wanted absolution before heading down to ‘the pile’ because you didn’t know what was going to explode next, what was going to fall down,” he said.

In addition to ministering to the firefighters, the priest blessed the bodies of many of the FDNY’s 343 fallen heroes, including Franciscan Father Mychal Judge, the beloved FDNY chaplain and first certified casualty of 9/11.

For several months following 9/11, Smith would commute almost daily from his parish to ground zero, where he continued to offer support to the firefighters, including his brother Patrick, who was among those participating in the recovery efforts.

He said his faith helped sustain him through the difficult work and grueling schedule. “Prayer, adrenaline and the Holy Spirit,” were the emboldening forces, he said, adding: “I had a sense that God was with me.”

Referring to his vocation as “a ministry of presence,” he said he spent time with the firefighters when they were working at ground zero and during their meals and rest breaks.

“I appreciated being a priest and a lot of people appreciated me being a priest. A lot of guys said, ‘Father, thank God you’re down here with us.’ … I felt needed.”

Smith was also present to the bereaved members of the fallen firefighters’ families. He estimates that he concelebrated 30 to 40 funeral Masses of firefighters, sometimes two or three in a single day.

“I knew a lot of the guys,” he said.

He also had been friendly with a number of people who worked inside the towers. One of his former parishes, St. Mary Church in Manhasset, lost 22 parishioners and alumni from its elementary and secondary schools, the majority of whom Father Smith had known personally. He concelebrated several of those funeral liturgies.

“I remember a year or two after 9/11 looking at a list of victims to see how many people I actually knew,” Smith said. “It was about 60. Sixty friends that I had contact with and knew their families. They were firefighters, guys from Cantor Fitzgerald and the other financial groups at the Trade Center.”

Like many emergency responders who served at the World Trade Center site on 9/11 and post-9/11, Smith developed health issues related to the toxic conditions of the environment.

“I have chronic sinusitis. I have sleep apnea. I’ve had some skin cancer,” he said. “All have been certified as 9/11-related.”

His brother Patrick, meanwhile, was forced to retire from the FDNY in 2006 with a 9/11-related respiratory illness.

Smith said he has proactively addressed the emotional scars that he bears from his time at ground zero. “I go to counseling,” he said. “It helps, especially on the (9/11) anniversaries. If you’re going to do trauma counseling, it’s not a bad thing to check in with somebody from time to time.

“The first couple of years, I’d have nightmares, flashbacks, a lot of that stuff.”

The priest’s 9/11 recollections also include positive memories of a time when people expressed their appreciation for the firefighters, police officers, construction workers and many others who pitched in at ground zero.

“At night, when you left the Trade Center, there would be people on the streets with big signs saying: ‘Thank You.’ They’d hand you a bottle of water or a peanut butter and jelly sandwich made by a school kid in Connecticut.”

Smith fondly remembers strangers chatting with and helping one another, a byproduct of the collective pain people shared and their desire for healing in the wake of the catastrophe.

He said he misses the post-9/11 period that was marked by a heightened degree of charity and fellowship, along with intense national pride and unity.

“It petered out over time to the point today where we’re probably yelling and screaming at each other a lot more than we should,” the priest said.

“You wish that some of the lessons we learned from 9/11 would have been passed on, like reaching out to one another, forgiving one another, being a little more patient with one another.”

The most important lesson, he said: “Cherish every single day.”