NEW YORK – Bishop Mark Seitz of El Paso considers the process temporary religious worker visa (R-1 visa) recipients endure to maintain lawful status a “race against time,” with federal processing backlogs making it difficult to satisfy different permissions and expiration dates.

The problem isn’t new. Although, it’s one that Seitz, other bishops, and legal immigration experts say was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and has hardly eased after two years, leaving both the religious workers and organizations they represent in precarious situations.

The United States Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS) has taken steps to improve the process this year, but those efforts aren’t viewed as enough.

“I have heard from many of my brother bishops that they’re all experiencing difficulties with the R-1,” Seitz, the incoming U.S. Bishops’ Conference migration chair, told Crux. “To know that there are people serving the church right now just helping people every day – visiting the sick, preaching, offering the sacraments – we’re making it extremely difficult for them.”

Auxiliary Bishop Mario Dorsonville of Washington, the current USCCB migration chair, told Crux that the USCCB has expressed its concerns to USCIS to no avail.

“For over a year now the USCCB has made it a priority to address ongoing issues related to processing delays in religious worker visas, and the program has been slower than ever which has had a significant impact on the church’s ministry throughout the country,” Dorsonville said.

Troubles from start to finish

The processing troubles begin before a religious worker ever steps on U.S. soil.

When a religious worker wants to come to the U.S. the first step is the employer must submit a petition to USCIS on the worker’s behalf. That petition can be submitted up to six months before the employee’s start date. In a pre-COVID-19 world that petition took up to six months to process. In a COVID-19 world that time has increased. The processing time as of March 17 at the USCIS California service center is 7.5 to 10 months, according to the USCIS website.

RELATED: Thirteen priests in Arkansas face uncertainty over their immigration status

“It affects not just the religious worker. It affects the organization as well,” Elnora Bassey, a policy advocate for the Catholic Legal Immigration Network, Inc. (CLINIC) told Crux, noting that the delay could force religious workers to miss their start date, and force their employers to figure out how or if to fill that position in the meantime.

That 7.5-10 month timeline, however, is just the first of potential processing woes.

Once that petition is processed the religious worker has to request the R-1 visa through the State Department, which involves an interview at the U.S. consulate in the worker’s home country. Once that process is approved the last step for the worker is going through the U.S. Customs and Border Protection at a U.S. port of entry.

A religious worker’s R-1 visa can last up to five years split into two two-and-a-half year stints.

The longest backlog in the entire process comes towards the end of that first two-and-a-half years. At that time the employer can file the same petition they did to get the religious worker to the U.S. to extend the R-1 visa for another two-and-a-half years. There’s a 180-day grace period in case the renewal isn’t processed before the first stint finishes.

If after that 180-day grace period the extension still isn’t processed, the religious worker has to stop working or they run the risk of violating their status.

Around the same time, after two years working in the U.S. on an R-1 visa, a religious worker can file what’s called an I-360 form, which is the first step towards becoming a permanent resident if they intend to stay in the U.S. beyond the five years allotted by the R-1 visa.

The government’s longest backlog is in processing the I-360 form. The time fluctuates. On March 17, the USCIS website said the processing time at the California service center is 17.5 to 23 months. Last week it was 23 to 29.5 months.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, it took about six months, Bassey said.

“The reason why the processing delays are such a major issue, especially for the I-360 stages, is because if it’s taking two plus years to process an I-360 and a religious worker only has two-and-a-half years left in R-1 status, if that I-360 is not approved before their status runs out the religious worker is going to have to go home,” Bassey said.

“They don’t have a choice and that’s what a lot of the U.S.-based religious organizations are facing right now is that they are having to send the religious workers back home,” she continued.

USCIS declined Crux’s request to comment on the processing delays.

After a religious worker’s I-360 form is processed they can apply for permanent residency through a green card application. At the same time, they file for an employment authorization card that allows them to work in the U.S. for two years after their five years under the R-1 visa expires, and they wait for their green card application to process.

The employment authorization card processing, however, is also delayed. Therefore if a religious worker’s five years under the R-1 visa expires along with another 180-day grace period without receiving an employment authorization card they are again forced to stop working.

The employment authorization card application takes 7.5 to 14.5 months at the California Service Center, according to the USCIS website. The government required those applications to be processed in 90 days up until 2017 when the rule was abandoned. Bassey said the backlog has increased since, and the pandemic has only made matters worse.

“When there’s all of these delays from beginning to middle to end it puts everyone in a bind and that’s why we’re fighting so hard and advocating so hard for USCIS to do something about the delays from beginning, middle to end,” Bassey said.

CLINIC represents over 800 religious workers in the United States.

Remedies

Dorsonville said one solution the USCCB alongside interfaith leaders have advocated is for USCIS to receive greater funding from Congress to address the issues through an overhaul of the current operation – hiring more staff and investing in modernization of the systems.

“On one of our last calls with them one of the points was that they were trying to jump from paperwork to computers and that was a long delay because they don’t have more tools to do it and the budget is the same,” Dorsonville said.

Olga Rojas, counsel for the Archdiocese of Chicago, acknowledged that the recent drop in processing times of the I-360 form is a step in the right direction, but still not enough. She suggested USCIS allow for concurrent filing of the I-360 and the green card application.

“It would give us more time,” Rojas told Crux.

One remedy Bassey said CLINIC has advocated is increasing the grace period of 180 days to 240 days to give everyone more time. She noted that making premium processing more accessible so more organizations can expedite the process would be helpful, as well.

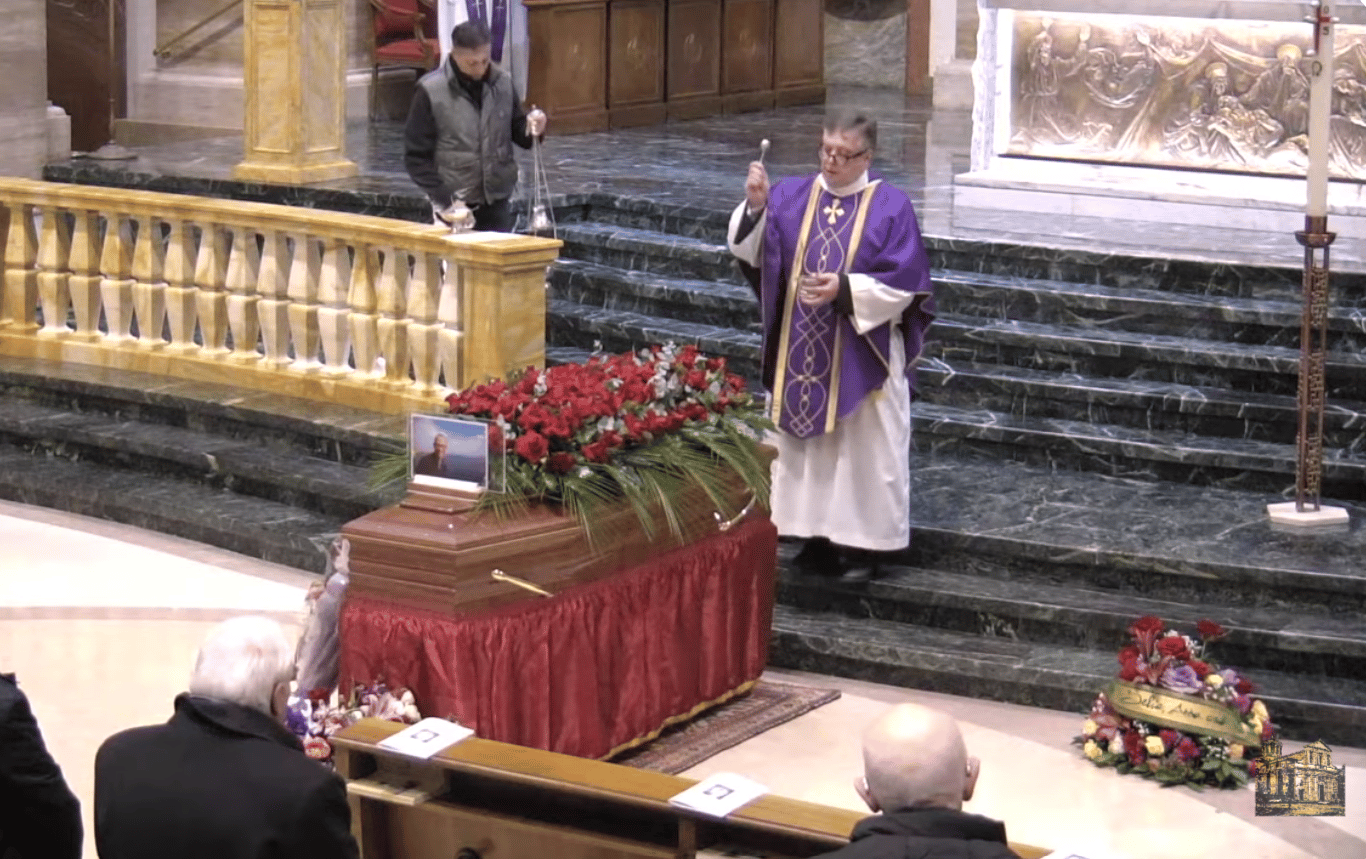

Bassey added that, in general, it’s also important for USCIS to recognize the value religious workers bring to the communities they serve in roles like celebrating Mass and presiding over weddings and funerals, caring for the sick, pastoring and counseling young adults, and as essential workers throughout the pandemic.

“They just bring joy and comfort to the communities they serve,” Bassey said.

Follow John Lavenburg on Twitter: @johnlavenburg