ROME — When you talk to people taking part in the 2015 Synod of Bishops on the family and ask where things stand, one observation you’ll often hear is that public impressions of the event and the actual experience of it are two very different things.

In the media and in the blogosphere, many bishops say, one gets a false sense of a savage war of all against all inside the synod hall, of tensions and personal animosities, of plots and rival camps.

For sure, those impressions haven’t come out of thin air. Cardinal Donald W. Wuerl of Washington, DC, gave a recent interview to America magazine complaining of some bishops voicing suspicions about the synod “surreptitiously, sometimes half-way implying, then backing off and twisting around,” suggesting that perhaps it’s because they just don’t like Pope Francis.

Yet on the inside, most participants report, such tensions are not the top note. Instead, they say, the atmosphere is generally calm and cordial, marked by real differences, but also by general respect and a desire to work together.

“Some people are making out that internal to the synod there are all kinds of horrible things going on, but there really aren’t,” Cardinal Daniel N. DiNardo of Galveston-Houston told Crux on Sunday. “People who have just said something opposed to one another then hang out over the coffee breaks together.”

If there’s merit to claims of a gap between perception and reality, what explains it?

Here’s a possibility worth considering: Maybe the synod’s protagonists just aren’t the crude stereotypes they’re sometimes made out to be, and are capable of greater subtlety and mutual understanding than one might imagine.

We got two hints in that direction on Monday.

One came in the form of Archbishop Mark Coleridge of Brisbane, Australia, who took part in the Vatican’s daily briefing.

Coleridge is on record saying he can’t embrace the “Kasper proposal,” meaning the idea of allowing divorced and civilly remarried Catholics to receive Communion championed by German Cardinal Walter Kasper. He used the briefing to say that while he has “no idea” how the synod at large stands, his impression is that support for Kasper “may have dwindled.”

That would probably be enough in some quarters to mark Coleridge as an obstacle to change, but that certainly wasn’t the tone of his presentation on Monday.

Instead, Coleridge argued that the 2015 synod shapes up as a “language event,” echoing the Rev. John O’Malley’s well-known description of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), in which the Church doesn’t betray its doctrine, but shifts the way it’s phrased to make it more accessible and capable of dialogue.

Coleridge expressed a desire to find new language for Church teaching on several fronts – the “indissolubility” of marriage, the “intrinsically disordered” nature of homosexual acts, calling divorce and civil remarriage “adultery,” and so on.

In general, he said, the Church needs an argot that comes off as more “positive, less alienating, less excluding.” For his trouble, Coleridge drew some blowback on the Internet, which he described in a tweet:

https://twitter.com/ArchbishopMark/status/656102420196532224

The divide between pro- and anti-Kasper positions is often assumed to be a bellwether of the clash between advocates of reform and the status quo, but Coleridge illustrates that things are more complicated.

Also on Monday, Archbishop Charles J. Chaput of Philadelphia sat down for an interview with Crux. A fuller version will be published shortly, but among other topics he discussed the same idea of finding new language.

In the abstract, one might assume Chaput wouldn’t be receptive. He’s seen as a leader of the conservative wing of the Church, and as the synod has rolled on, he’s offered a few reminders of why – publishing a column in the Wall Street Journal, for instance, saying that the more reform-minded bishops insist they’re not changing doctrine, the more other bishops get nervous.

Yet here’s Chaput on using the phrase “intrinsically disordered” to talk about gays and lesbians:

“I think it’s probably good for the Church to put that on the shelf for a while, until we get over the negativity related to it,” he said. “That language automatically sets people off and probably isn’t useful anymore.”

To be clear, Chaput is hardly suggesting the Church jettison the teaching behind the phrase.

“It means that same-sex attraction is not part of God’s plan, and we can’t deny that’s what the Church thinks,” he said, stressing that whatever new language is adopted “absolutely cannot” obscure this point.

Yet Chaput acknowledged that in the court of public opinion, phrases such as “intrinsically disordered” are often a losing proposition. He said he doesn’t know what the appropriate substitute would be, but is open to finding one.

Much like the Kasper proposal, the pro and contra positions on the push for “new language” are often assumed to mirror the liberal/conservative fault line, but Chaput demonstrates that isn’t always so.

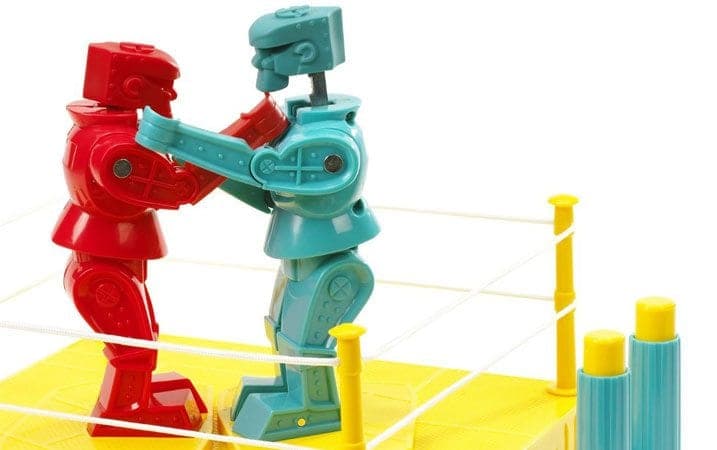

If the 2015 Synod of Bishops on the inside doesn’t really feel like an ideological slugfest, Coleridge and Chaput both suggest an explanation as to why: Its participants aren’t Rock’em Sock’em Robots, but complicated human beings whose thinking can surprise you if you give it a chance.

That, by many accounts, has been the reality of the event. Soon we’ll know if it’s also the reality of the synod’s conclusions, which the bishops are drafting now and which are scheduled for a vote on Saturday.