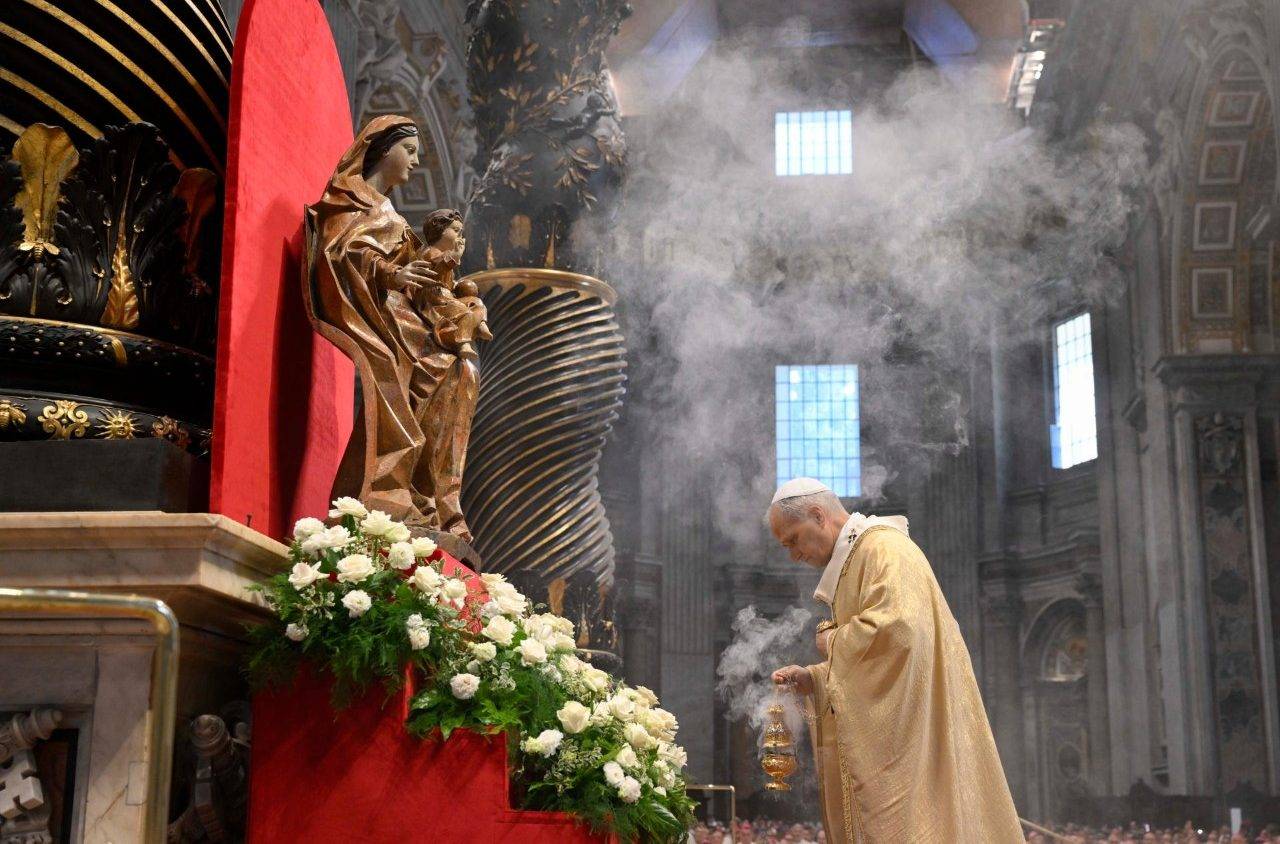

ROME — Because it’s the third rather than the first, Pope Francis’ Sunday visit to Rome’s Great Synagogue may not have the groundbreaking feel of St. John Paul’s outing in 1986, nor the historic resonance of Benedict XVI’s in 2010 — a pope who had once, albeit against his will, been a member of the Hitler Youth.

Yet that doesn’t mean this pope isn’t invested in Catholic/Jewish relations, or that this visit is just another day at the office.

As an Argentine, Francis’ approach to Catholic/Jewish dialogue is largely devoid of the horrific legacy of the Holocaust that tends to dominate European conversation between the two faiths. However, it’s certainly not free of the impact of violence, and the pontiff’s interest in outreach to Jews is part of his national identity.

When he was still the archbishop of Buenos Aires, then-Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio co-authored a celebrated book, “On Heaven and Earth,” with his friend, Argentine Rabbi Abraham Skorka.

The two religious leaders also recorded 31 televised discussions about topics of social and religious interest in Argentina.

“All we did was offer people the fruit of our relationship,” the rabbi said in a 2014 interview. “The Bible offers a clear, simple response to the concerns of our age,” which, he said, Pope Francis continues “to show in his daily teachings.”

The Jewish community of Buenos Aires is the sixth largest outside of Israel, and the largest in Latin America. The city’s Jewish footprint can be glimpsed, for instance, in the fact that it has the only kosher McDonalds outside Israel, located in a Buenos Aires shopping center.

In the early 1990s, the Jewish community in Buenos Aires was the target of two major terrorist attacks, one against the Israeli embassy in 1992 and another against a Jewish center in 1994.

In 2010, when Bergoglio visited the site of that 1994 attack, he described it as “another link in the chain of suffering of the Jewish people.”

Stories of the Argentine pope’s personal investment in dialogue with Jews are almost endless. As archbishop of Buenos Aires, he participated in Hanukkah celebrations, he invited Skorka and their common Muslim friend Omar Abbud to his trip to the Holy Land in 2014, and when the rabbi visits him in the Vatican today, the pontiff always makes sure there’s kosher food available.

He has repeatedly condemned anti-Semitism, and also the right of Israel to live in peace and security.

“To attack Jews is anti-Semitism, but an outright attack on the State of Israel is also anti-Semitism. There may be political disagreements between governments and on political issues, but the State of Israel has every right to exist in safety and prosperity,” he told representatives of the World Jewish Congress who visited him last October.

Yet as policy-maker, he hasn’t always received perfect scores from some Jews.

He’s at least equally as supportive of Palestine as he is of Israel. On his watch, the Vatican signed its first-ever treaty in June 2015 with what it officially recognized as the “State of Palestine.”

During a visit to Israel and Palestine in 2014, Francis made an unscheduled stop to pray at the Israeli separation wall in Bethlehem. It was, as his aides conceded later, a silent statement against a symbol of division and conflict.

Many Israelis saw it as a propaganda stunt, an impression reinforced by the fact that Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas immediately promised to create a postage stamp commemorating the moment. The next day, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu called on the pontiff to make an unscheduled visit to a memorial for Israeli victims of terrorism.

Soon after his trip to the Holy Land, Francis hosted then-President Shimon Peres of Israel and Abbas in the Vatican gardens to pray for peace in the Middle East.

Francis’ attitude regarding one of his predecessors, Pope Pius XII, also remains a question mark for some Jews, as he hasn’t taken a stand either in favor or against declaring him a saint.

The wartime pontiff’s alleged silence during the Holocaust has been a constant source of conflict between Catholic and Jews over the years.

One of the few times Francis referred to the issue was on the plane back from the Holy Land.

“The cause is open … I looked into it and no miracle has been found yet,” he said. “So the process has stalled. We have to respect the reality of this cause. But there’s no miracle, and at least one is required for beatification. I can’t think of whether I will beatify him or not.”