ROME – When a strong pope with a clear social agenda intersects with a world leader who shares the same basic outlook, and one who’s willing to put elbow grease behind it, sometimes history can change.

With the support of King Philip II of Spain, for instance, St. Pius V promoted a “Holy League” that turned back a possible Ottoman Muslim conquest of Europe at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571. Four centuries later, St. John Paul II and US President Ronald Reagan joined forces in a successful effort to bring down Soviet Communism.

Though with a different set of priorities, Pope Francis has a similar ambition to shape history. He wants to steer it away from what he’s called the “globalization of indifference” to the poor, refugees, and other victims of a “throw-away culture”, and he wants to end a Third World War he believes is being fought today in “piece-meal” fashion.

The question facing Francis in 2016 is: Who’s the political partner who could help him move the ball? In truth, it’s not easy to answer.

For centuries, the Vatican instinctively looked to the great Catholic powers of Europe as its natural allies. Today, that logic no longer holds.

In Western Europe, traditionally Catholic nations such as France and Spain are mired in domestic difficulties, and their strongly secular ethos is suspicious of ecclesiastical leadership in politics. In the East, the most staunchly Catholic nation, Poland, is currently led by a nationalist government hostile to Francis’ priorities on several fronts, from the treatment of refugees to the use of fossil fuels.

(The political climate in Poland should make Francis’ scheduled visit in late July to lead the Church’s World Youth Day highly interesting.)

More recently the Vatican has tended to rely on the United States, but that too seems a dicey proposition going forward.

Obama and Francis did come together in the historic reopening of relations with Cuba, but veteran Italian journalist Piero Schiavazzi recently made the interesting observation that Francis could be in for the same disappointment today that befell John Paul II after the collapse of Communism.

John Paul wanted to bring Eastern and Western Europe back together, hoping the East would revive the spiritually moribund West, only to watch Western consumerism and secularism triumph. Likewise, Schiavazzi suggests Francis has helped reunify the Americas but he may be unhappy with the aftermath, as a conservative political wave away from his preferred brand of social democracy seems to be building in Latin America, including his native Argentina, and the United States could well be on the brink of electing Donald Trump.

Even if Hillary Clinton prevails in 2016, that’s not necessary a forecast for an era of good feelings. During the last Clinton administration, the Vatican and the White House fought titanic battles over population control and abortion during United Nations conferences in Cairo and Beijing.

Who does that leave?

One option would be Vladimir Putin, recently crowned by Forbes as the most powerful person in the world, and Francis and the Russian leader have done business on several fronts. In September 2013 they aligned to resist calls for Western military intervention in Syria, and Putin’s pledge to defend persecuted Christians in the Middle East is something Francis values.

On the other hand, Francis also has repeatedly criticized Russia’s intervention in Ukraine, and in any event a marriage between the “Pope of Mercy” and, arguably, the least merciful public figure on the planet, doesn’t quite seem a match made in heaven.

Francis could look to China, the world’s emerging superpower, under Xi Jinping. (The pontiff and the Chinese premier finished fourth and fifth on the Forbes power countdown.)

Yet the two men didn’t meet when they were both in the United States at the same time in September, suggesting that a long-standing chill between Beijing and Rome has yet to thaw, and until China rethinks its policies on religious freedom, a partnership could only go so far.

One might think a “Pope of the Peripheries” would naturally look to the developing world for strategic partnerships, and there are promising options. What I’ve called the PINS nations – the Philippines, India, Nigeria, and South Korea – all have dynamic, growing Catholic communities, and they all are countries positioned for leadership.

Yet for various reasons, each has its drawbacks as a potential partner. India, for example, is ruled by a Hindu nationalist government hostile to the country’s Christian minority, while Nigeria is engulfed by internal woes, chiefly Boko Haram. The Philippines is facing its own election cycle in 2016, and South Korean foreign policy often begins and ends with its neighbor to the north.

Perhaps the answer for Pope Francis is that there simply is no Philip II or Ronald Reagan awaiting him in 2016, meaning a single world leader with vision and clout whose interests align neatly with his own.

Instead, if Francis is correct that a Third World War is being fought piece-meal, perhaps the only response may be an equally piece-meal brand of diplomacy, crafting short-term alliances with various figures on specific issues but refraining from putting all his eggs in one basket.

So far, the piece-meal war denounced by Francis seems to be doing just fine without any overarching leadership. It remains to be seen if a similarly ad-hoc kind of peacemaking, inspired by the pontiff but without a clear dancing partner, can be equally effective in resolving it.

* * *

What if the pope throws a jubilee and no one comes?

Philosophy’s classic head-scratcher asks if a tree falls in the forest but no one’s there to hear it, does it make a sound? In 2016, Pope Francis may face his own personal version of that conundrum: If a pope calls a jubilee year but no one shows up, did it actually happen?

That’s a tongue-in-cheek way of putting things, because to suggest “no one” may turn out for the Holy Year of Mercy that Francis has set to run from Dec. 8, 2015, to Nov. 20, 2016, is wildly overstated. Plenty of pilgrims have already taken part in its early moments, including the opening of a Holy Door at St. Peter’s Basilica on Dec. 8 and on New Year’s Day at St. Mary Major, and the city of Rome is expecting throngs of additional visitors during the year.

On the other hand, Vatican statistics released at the end of the year show that attendance at papal events in December was down significantly with respect to 2014, having dropped 30 percent from the same month in the previous year. Crowd totals fell from 461,000 last December to 324,000 in December 2015, despite the fact that there were actually a few more events this December due to the beginning of the Holy Year.

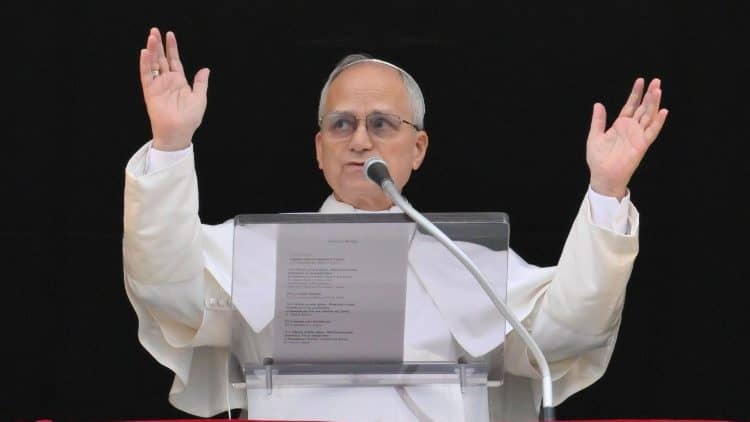

The decline was palpable during the holiday period, as crowds for the pope’s Urbi et Orbi address on Christmas Day and his noontime Angelus on New Year’s Day were enthusiastic but notably smaller than usual.

Based on the diminished turnout, one Italian newspaper carried the headline: “A ‘Jubilee Effect’ Just Isn’t There.” Some Italian commentators began rolling out the word “flop” to describe the jubilee’s early phase.

Most observers believe a primary reason for the small crowds is widespread concern over security in the wake of the November terrorist attacks in Paris, which has produced alarm over large public gatherings all over Europe. It’s had a chilling effect on tourism generally, with officials in the Italian province that includes Rome also reporting below-average hotel occupancy rates during the holiday period.

Every day seems to bring a new security scare. On New Year’s Day, for instance, there was a report of a suspicious package discovered on Rome’s subway system which discouraged many locals from using public transportation.

Since terrorism does not seem on the brink of disappearing, it could cast a shadow over the entire year. If a thirty percent drop for Francis’ events were to continue throughout 2016, it would mean that almost two million fewer people will see him during his all-important jubilee year than in the previous two.

There may, however, be two other forces behind the drop-off, both of which may not necessarily be alarming for the kind of jubilee Pope Francis hopes to lead.

For one thing, Francis created unusually high expectations for crowd size in the early stages of his papacy. Official Vatican figures estimate that Francis drew almost six million people to public events in Rome during 2014, after setting a record total of 6.6 million in 2013. Both represented astonishing spikes in comparison to the turnout for Pope Benedict XVI, who in 2011 drew 2.5 million.

Since Francis’ election, virtually every Wednesday General Audience and Sunday Angelus address in Rome took on the feel of a major canonization Mass, with massive crowds forcing police to block off portions of the broad Via della Conciliazione leading to St. Peter’s Square.

To some extent, it could be that Francis’ totals were always destined to come back to Earth, and December 2015 may go down as the moment when that levelling-off began to happen. For a pontiff who’s groused about being dubbed a “superman,” that may not seem an entirely bad thing.

In addition, Francis has said he doesn’t want the Year of Mercy to be celebrated exclusively in Rome, but also in local parishes and dioceses all around the world.

For the first time in the history of the Church’s jubilee tradition, which stretches all the way back to Pope Boniface VIII in 1300, individual dioceses have been asked to open their own Holy Door, to be called a “Door of Mercy,” either in the local cathedral or in a church of special meaning or a shrine of particular importance. People who want the plenary indulgence associated with passing through a holy door can do so without the need to come to Rome.

During a press conference in May, Italian Archbishop Rino Fisichella of the Pontifical Council for the Promotion of New Evangelization — more or less the “director” of the Holy Year — tried to underscore its originality.

“In order to avoid any misunderstanding,” he said, “it is important to reiterate that this Jubilee of Mercy is not, and does not intend to be, the Great Jubilee Year of 2000.”

His reference was to the holy year held under St. John Paul II to mark the turn of the millennium in 2000, widely considered the biggest blockbuster in the history of jubilees. It featured a special event in Rome virtually every day, including – this is no joke – jubilee days for pizza chefs, motorcycle riders, and circus performers.

The city of Rome officially estimates that 24.5 million people took part in John Paul II’s jubilee at some point during the year 2000; Censis, an Italian research institute, put the total at 32 million.

Francis seems to have in mind a less Rome-centric event. On Ash Wednesday this year, which falls on Feb. 10, he’ll commission a special corps of priests, called “Missionaries of Mercy,” part of whose charge is to go out and organize special events connected to the jubilee for local churches around the world.

If crowds are smaller in Rome this time, therefore, it won’t necessarily mean the jubilee is a flop. It could simply signify that it’s working according to design, as some share of potential pilgrims decide to observe the event in their own backyards.

For those reasons, the party most likely to be disappointed if the expected tidal wave of visitors to Rome never materializes almost certainly won’t be Pope Francis.

Instead, it will be Rome’s hotel operators, tour guides, cab drivers, restauranteurs, and gift shop owners, all of whom have been counting on the jubilee to boost their flagging bottom lines. The pope may be happy with a smaller and less spectacular event, but the people who make a living from his star power probably shouldn’t be expected to share the sentiment.