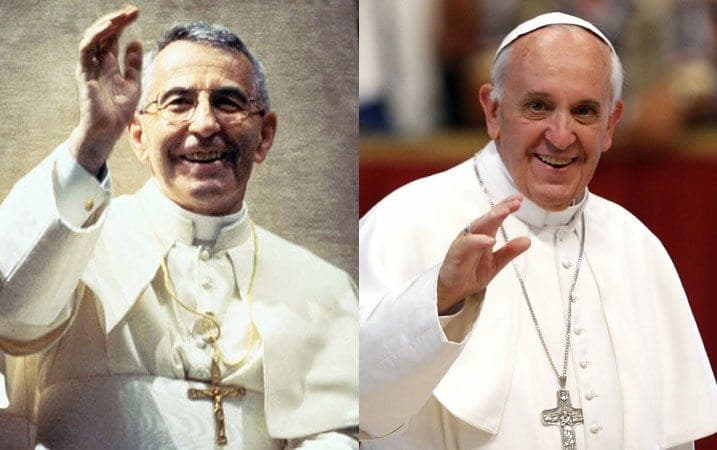

In 1963, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated, and Americans ever since have pondered what might have been. Fifteen years later, the Catholic Church faced the same question about Pope John Paul I, the “Smiling Pope” who exuded warmth and simplicity, and who died of a heart attack on Sept. 28, 1978, after just 33 days in office.

Americans may still be uncertain, but today Catholics basically have an answer: Had John Paul I lived, he may well have been much like Pope Francis.

The thought occurs in connection with release of a new interview book with Francis, the first book he’s released as pope: “The Name of God is Mercy”, a conversation about his jubilee Holy Year of Mercy in 2016. Published simultaneously in 80 countries, it’s the fruit of an exchange with Italian Vatican writer Andrea Tornielli. Its official release date is Wednesday; copies were provided to news outlets early.

The Vatican will mark the book launch Tuesday with a panel discussion featuring secretary of state Cardinal Pietro Parolin and actor Roberto Benigni of “Life Is Beautiful” movie fame.

There isn’t a great deal in terms of news flashes, but two points are of interest.

One hot-button issue in Catholicism today, which Francis is expected to address in a forthcoming document drawing conclusions from two summits of Catholic bishops, is whether Catholics who divorce and remarry outside the Church ought to be able to receive Communion. (Currently, they’re barred.)

In the book, Francis tells the story of a man who married one of the future pope’s nieces before his previous marriage had been declared null by a Church court, and thus was excluded from the sacrament. The pope said the husband went to church every Sunday and said to the priest, “I know you can’t absolve me but I have sinned, please give me a blessing.”

The pope calls that man “religiously mature.” It could be read as a hint that Francis is inclined to urge understanding, but not necessarily to change existing discipline.

At another point, Francis comments on his famous 2013 soundbite “Who am I to judge?” about gay people.

The pontiff says he was “paraphrasing by heart the Catechism of the Catholic Church,” referring to the official compendium of Church teaching.

“You can advise [gay people] to pray, show goodwill, show them the way, and accompany them along it,” he says, again suggesting that he supports compassion and inclusion, but not a revision of Catholic teaching.

On the whole, the book offers a treatise on Francis’ understanding of mercy.

“The Church does not exist to condemn people, but to bring about an encounter with the visceral love of God’s mercy,” he says, conceding bluntly that Catholicism hasn’t always pulled it off.

“When it comes to bestowing grace, Christ is present,” he says, quoting the 4th-century St. Ambrose. “When it comes to exercising rigor, only the ministers of the Church are present, but Christ is absent.”

Francis rejects “a formal adherence to rules and to mental schemes,” insisting that “mercy is the first attribute of God.”

Scanning the brief text, it’s striking that although Francis cites the five other popes since the opening of the Second Vatican Council in the mid-1960s — St. John XXIII, Blessed Paul VI, John Paul I, St. John Paul II, and Benedict XVI — the one he alludes to most is John Paul I.

Francis cites “Papa Luciani,” referring to his given name, five times. That’s especially notable given that the other four popes reigned an average of 13 1/2 years, while John Paul I was in office for barely more than a month.

Despite that brief stay — the 10th shortest papacy ever, and the briefest since Leo XI’s in the early 17th century — in his day, John Paul I was a sensation.

He came off as exactly what most Catholics pray their leaders will be: warm, compassionate, genuinely happy to be with ordinary people, a man of obvious faith who didn’t wear his piety on his sleeve or take himself too seriously. He pioneered the simplification of the papacy by dropping the royal “we,” declining coronation with the papal tiara, and discontinuing use of the sedia gestatoria, or portable throne.

Sound like anyone you know?

Famously, John Paul I, in one of just a handful of public utterances as pope, said that God is so merciful as to be “even more” a mother than a father.

“God has such tender love for us, even more tender than the love that a mama has for her children,” he said, quoting the Old Testament prophet Isaiah. “Little children, when they are sick, have one more reason to be loved by their mothers, and so do we: if we are sick with wickedness, if we have gone astray, then we have one more reason to be loved by the Lord.”

Those lines easily could have been spoken by Francis, and in fact, he’s pronounced some version of them countless times.

That’s not to suggest Francis doesn’t have a great deal in common with his other predecessors, too — for instance, St. John Paul II created a Feast of Divine Mercy, helping set the stage for Francis’ jubilee — but the bond with John Paul I is remarkable, especially as he tends to be the “forgotten pope” of the modern era.

A US-based association devoted to John Paul I has petitioned Francis to speed up the process of his beatification, a key step on the road to sainthood, during the Year of Mercy. If the pontiff’s new book is any indication, that might not be a bad bet.

* * * * *

Classifying the Catholics who have a beef with the pope

This week I heard from a reporter I know for a political site in Belgium, who was doing a piece on Pope Francis. He was struggling to put together the pontiff’s personal popularity with statistics showing drops in church attendance, and also indications of internal Catholic resistance to the pontiff.

His working theory pivoted on a distinction between what he called “soft” Catholics, meaning those on the margins of the Church, and “deep” Catholics, meaning people highly committed to the faith. The reporter wanted to know if I agreed that Francis’ appeal is mostly to “soft” Catholics, and his problems are with the “deep” group.

My reply was that like any other way of dividing the pie, his distinction captures part of the picture, but not all.

It’s true that some of who he was calling “deep” Catholics get nervous when the world applauds the pope, any pope, because they fear something must have been lost in translation.

On the other hand, there are also plenty of “deep” Catholics — people who go to Mass regularly, who believe what the Church teaches, and who make a sincere effort to practice it — who are strongly pro-Francis. One place to find them is many of the religious orders in Catholicism, including his own Jesuit community.

If the distinction between “soft” and “deep” Catholics doesn’t quite explain the diversity in reaction, what does?

I said I’d put at least five other ways of analyzing Catholic life into the mix.

1) There’s the usual taxonomy of liberals, conservatives, and moderates.

Roughly, I define a “liberal” Catholic as someone who’d like to see Church teaching change, for instance on female priests or homosexuality; a “conservative” as someone who not only supports the teaching, but wants it expounded and enforced with conviction; and a “moderate” as someone who embraces the teaching, but would like to see greater compassion and flexibility in implementation.

Put that way, Francis’ natural base is among moderates. On both the left and the right, some Catholics are wary: liberals worried he won’t go far enough and conservatives convinced he’s already gone too far.

2) There’s the psychological distinction between personality types inclined to resist change, of any sort, and those eager for it, often before they even know what it is. In a faith as bound to tradition as Catholicism, that’s an especially keen force, because instincts on change are bound up with theological and spiritual convictions.

For good or ill, Francis is a break-the-mold sort of pope, so he doesn’t always play well with those who view change with alarm. (For the record, I share some of that aversion myself; just ask any of the waiters at my favorite restaurants in Rome who can tell you, with precision, what I order every single time I show up.)

3) There’s a distinction between what one might call “political” and “apolitical” Catholics.

A “political” Catholic is one who follows Church affairs, who reads, thinks, and talks about what the pope is doing, and develops his or her own views — whether the Latin Mass ought to be more widely used, for instance, or whether divorced and civilly remarried Catholics should be able to receive Communion.

An “apolitical” Catholic is one who doesn’t follow such matters, and doesn’t have strongly held opinions about them. For them, it’s enough to go to church on Sunday, pray a little bit, and feel closer to God.

This is not the same thing as a “soft” Catholic, because these people are often ferociously committed to the Church.

My grandparents were perfect examples. I recall once asking my granddad, virtually a daily Mass-goer, what he thought of John Paul II, and his startled reply was: “He’s the pope, son … what do you mean, what do I think of him?”

Francis’ problem, like any pope, is always going to be with the political group.

4) There’s the West and the rest of the world — or, to use Francis’ vocabulary, the “periphery” and the “center.”

Francis is a man of the periphery — both biographically, as the first pope from the developing world, and in terms of values and outlook. As a result, his strongest appeal is always going to lie there, and to some extent, the historic centers of the faith will always see him as not quite “their” man.

5) There’s social and economic class.

Francis’ incessant emphasis on poverty, not just as a social concern, but also a spiritual value, has left some middle class and affluent Catholics ambivalent, wondering if he sees any virtue in them or their lifestyles. (Not to mention, of course, wondering if he still wants their money.)

Simply put, sometimes he makes them feel guilty, which is always an unpleasant sensation.

Some of that guilt may be a healthy stimulus to an examination of conscience, but some of it may reveal a pope who hasn’t quite found a way to reach people who’ve achieved prosperity for themselves and their families through hard work, with integrity, and who don’t want to feel that their pontiff scorns them for it.

In sum, I told my colleague that if we’re going to tick off categories of Catholics with whom Francis may run into problems, there are at least seven overlapping subsets: “deep” Catholics, liberals and conservatives alike, people with change-related anxiety, political types, those at the center, and the (comparatively) wealthy.

His response? “That’s way too complicated,” he said.

Welcome to my world, my friend.