[Editor’s Note: This article was originally published on the web site of the Unione Cristiani Cattolici Razionali, the “Union of Rational Christian Catholics,” in Italy, and appears here in a Crux translation.]

From 1917 to the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia was governed by a regime that sought to combat religious belief and to impose atheism on its population. Nevertheless, there was a brief period in those decades in which the Communist authorities suspended their anti-religious campaign in order to gamble on a good relationship between church and state, and that was during the “Great Patriotic War.”

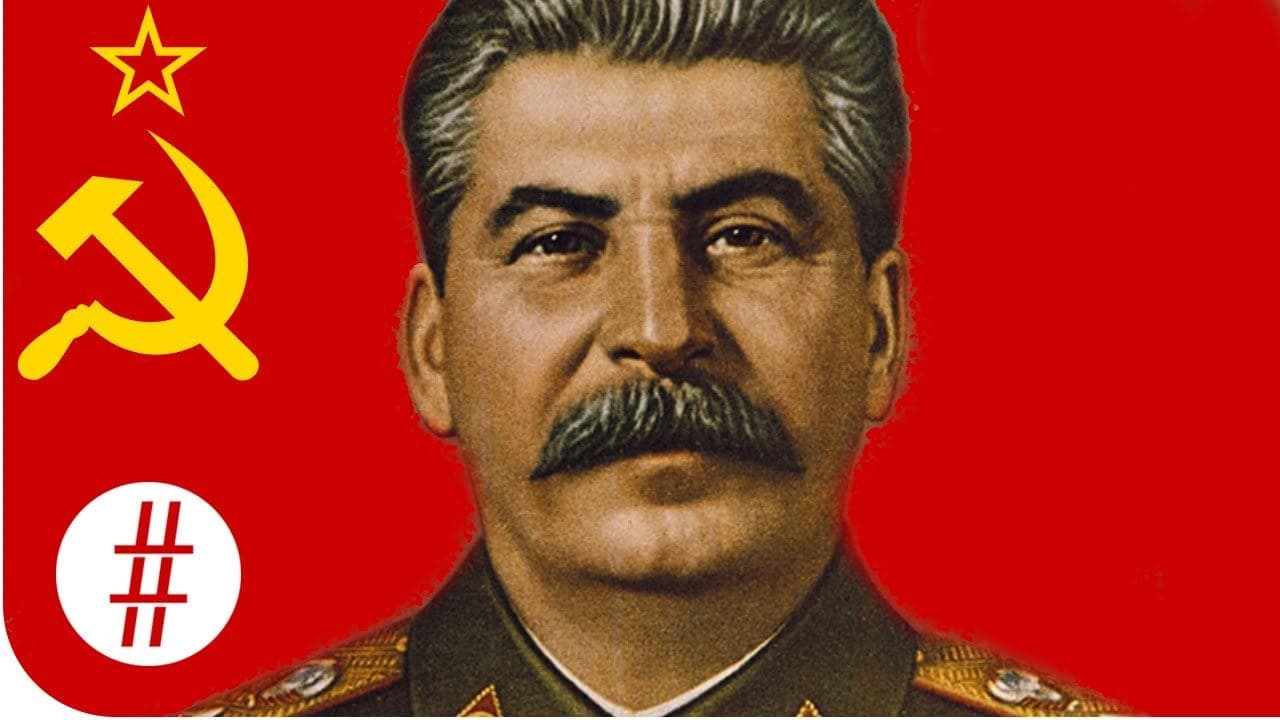

It may seem surprising that it was Stalin himself who adopted this policy, in that once he gained absolute power, he showed himself determined to continue Lenin’s religious policy, unleashing a ferocious anti-Christian persecution: During the 1930s, the number of priests plummeted to a few thousand, churches were destroyed, the Russian Orthodox weren’t permitted to have a Patriarch after 1926, and the population was forced to practice its faith in clandestine fashion.

Even when the Second World War broke out, the Georgian dictator didn’t change his approach – indeed, he extended his anti-religious provisions to the regions he conquered thanks to an alliance he worked out with Hitler though the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact.

However, when Germany invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, it completely changed the ecclesiastical policy of the country: Stalin stigmatized the anti-Christian activity of party fanatics, churches and seminaries were reopened, religious ceremonies were encouraged, the office of Patriarch was brought back, and the church was allowed to own property.

What drove the Secretary of the Communist Party to such a clamorous about-face? The explanation is to be found in the dictator’s goals.

In the first place, Stalin was perfectly well aware that the Russian people were not inclined to fight for Communism, so to mobilize the population it was necessary to make appeals to patriotism and tradition.

He knew the help of the Orthodox Church was fundamental, and his move showed itself to be far-sighted – the newly rediscovered freedom of cult was welcomed with enthusiasm by the faithful, as the overflowing churches for Easter in 1943 showed, and soldiers in great numbers attended religious ceremonies (even though Stalin never gave permission for chaplains to follow his troops.)

Also, the Orthodox Church responded positively to the regime’s request for support, to the point that Metropolitan Sergius (later Patriarch Sergius) appealed to the faithful to do everything they could to guarantee victory, and the church itself donated 150 million rubles to the armed forces that they had collected from the faithful.

Moreover, by loosening up on religious freedom, Stalin also served his objective of favorably impressing the Allies. He was aware that a good part of the anti-Soviet sentiment in the West, especially in the United States, was because of the persecution of the church. (On June 23, 1941, Roosevelt had compared the lack of religious freedom in Nazi Germany to that of Soviet Russia).

In order to demonstrate that state-imposed atheism was a thing of the past, Soviet representatives were sent to the Allied powers to furnish assurances about the Communist change of direction, foreign religious leaders were invited to visit Moscow, and Stalin himself told the English ambassador that, in his own way, he believed in God.

The Anglican Church mobilized to support the Soviet alliance, but in America few Christians believed in Stalin’s “conversion,” considering it (not without reason) a political move. Among those most decisively contrary to an alliance with Russia were the Catholics, given that Pope Pius XI in 1937 had put out the encyclical Divini Redemptoris condemning Communist ideology.

To placate religious Americans, Roosevelt tried to present the German state as even more hostile to Christianity than Stalin’s Russia. In October 1941, he declared that he was in possession of a 30-point program developed by Nazi party philosopher Alfred Rosenberg that foresaw the creation of a national German church, which would substitute the Bible with Mein Kampf and would replace the Cross with the sword and the swastika.

This document, which had an enormous circulation, would later be shown to be a fake. Yet the intention of Hitler to eliminate the Christian churches was real, given that the Fuhrer considered Christianity a “cordial Bolshevism, under the pretense of metaphysics,” and in the Third Reich various movements encouraged new forms of paganism such as the SS of Himmler.

Facilitating Roosevelt’s campaign, there was also a personal reassurance of Pope Pius XII, who made it known that while the encyclical of his predecessor condemned Communist ideology, it did not prohibit helping the Soviet Union in order to support the Russian people.

After four years of struggle, the Allied forces succeeded in defeating the armies of the Axis. There were multiple factors that decreed an Allied victory, but the result probably would have been impossible without Stalin’s religious policy.

Nonetheless, the new-found religious liberty in Russian territory didn’t last. Beginning in 1948, Stalin decided to break the “truce” and subjected the Orthodox Church to new persecutions.

Why did the Russian dictator, immediately after the danger of defeat in the war was past, resume the policy of spreading atheism by force, even though it had been shown to be counter-productive?

It’s explained by the fact that the actions of Stalin were driven by his ideology, and the end-game proposed by that ideology was the eradication of religion from society. In the end, however, the hunger for faith and the freedom to express it was just too strong to overcome.