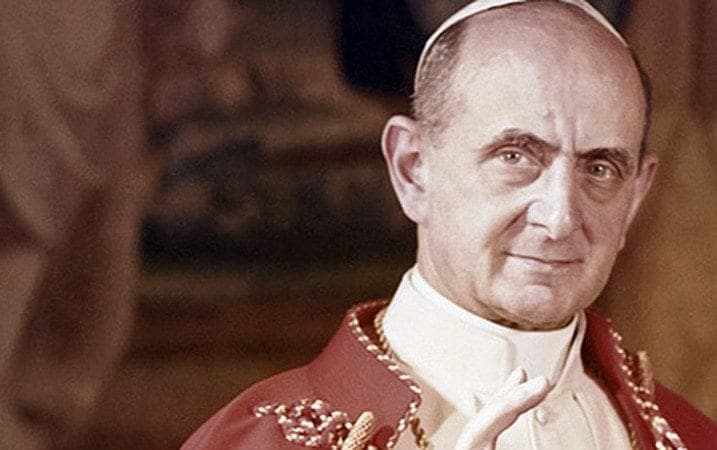

Wherever one chooses to start the story of the modern simplification of the papacy, a key point along the way has to be the first time the world really saw a pope display a broken heart in public, even flirting with rebuking God.

It happened on May 10, 1978, the 38th anniversary of which is today.

The day before, on May 9, Italian Prime Minister Aldo Moro was executed by a left-wing Italian terrorist movement called the “Red Brigades.” Moro was a close friend of Pope Paul VI, who had made great efforts to save him, and Paul was devastated by the loss.

Moro knew Pope Paul, now “Blessed Paul VI,” from their days together in FUCI, the Federation of Catholic University Students. In the short run, Moro’s murder sapped whatever strength Paul VI had left, arguably hastening his own death three months later.

Moro had been kidnapped 55 days earlier, while on his way to Parliament to savor what was to be his defining political achievement: the compromesso storico, a plan to bring Italy’s Communist Party into a governing alliance with the Christian Democrats in order to promote national stability. His policy of a cautious opening to the Communists tracked with Pope Paul’s own policy of Ostpolitik, or dialogue with the Soviet bloc.

Paul’s turmoil was clear from his public statements, both before and after his friend’s death.

In a rare departure from what was then still the customary royal plural of the papacy, Paul VI had addressed a first-person appeal to the terrorists to free Moro on April 23, 1978. In a note in the pope’s own handwriting published by Osservatore Romano, the Vatican newspaper, the pope wrote:

“I am writing to you, men of the Red Brigades … you, unknown and implacable adversaries of this deserving and innocent man, I pray to you on my knees, liberate Aldo Moro simply and without any conditions.”

According to Italian journalist Giovanni Bianconi, Vatican officials at Pope Paul’s urging had privately utilized prison chaplains in Italy to make contact with the leadership of the Red Brigades, offering to collect money to pay a ransom.

Former Italian Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti, who was in power at the time of Moro’s execution, later confirmed that Paul VI had offered to pay a large ransom to set Moro free. According to one report, the amount floated was U.S. $10 million. Other reports suggest that Paul VI even offered to take Moro’s place as a hostage to secure his release.

In the end, the kidnappers insisted upon the release of dozens of jailed Red Brigades militants, a demand the Italian government refused to meet. After being declared guilty in a show trial of crimes against the people, Moro was placed in the trunk of a car and riddled with ten bullets.

The next day, May 10, 1978, Paul VI was scheduled to meet with a group of young Italian children who had just received their first Communion. Unable to hold back his tears, Paul VI openly wept while calling Moro’s death “a bloody mark which dishonors our country.”

“We knew him from the years of his youth since he was a university student,” Paul VI said. “He was a good and wise man, incapable of doing harm to anyone, a very good professor and a political and government figure, a person of great value, an exemplary father and, what counts even more, a man of high religious, social and human feelings.”

“This crime has shocked every honest person in the world, the whole of society,” Pope Paul said.

“His premeditated and calculated slaying, carried out in hiding and without mercy, has horrified the city, all Italy, and has moved the entire world with indignation and pity. Everyone speaks of it, everyone is indignant. And even you, young people and children gathered in this basilica, are horrified and saddened.”

That outpouring shocked many in Italy and around the Catholic world, who were unaccustomed to witnessing popes emoting like that in full public view.

Three days later, Paul VI even uttered a rare display of something akin to protest against divine providence.

On May 13, the pope addressed himself to God in the Basilica of St. John Lateran, saying: “You did not grant our plea for the safety of Aldo Moro, of this good and gentle man, wise and innocent … who was my friend.”

By that stage in his papacy, Paul VI was not really a crowd-pleaser, still carrying the scars of battles that had erupted a decade earlier over his controversial encyclical Humanae Vitae affirming the Church’s traditional ban on birth control.

Yet his display of grief and unresolved spiritual anguish humanized Pope Paul, reminding the world that underneath the vestments and the symbols of office, beyond the controversial positions and claims to teaching authority, was a real flesh-and-blood person.

Today, of course, that’s not really a point that needs to be made, especially with Pope Francis, who always wears his personality on his sleeve. As difficult as it may be to imagine now, however, there was a time not so long ago when the humanity of the men who become popes was largely hidden from the world.

May 10, 1978, may go down as one of the key moments when all that began to change … a day when an almost unbearable personal loss compelled a pope to step out from behind the veil of office, setting a precedent upon which his successors, each in their own ways, have built.