MALAKAL, South Sudan — For thousands of displaced people who have found refuge inside a United Nations base in Malakal, a town in war-torn South Sudan, it’s a daily struggle to find food, water and medicine. Finding hope is even harder. For that, many of them look to Maryknoll Father Michael Bassano.

The missioner from Binghamton, New York, says his parish is a tightly packed maze of shacks constructed of scrap lumber and tin sheeting filled with people hiding from war.

“In Maryknoll, we believe we should be with people at the margins, and you don’t get any more marginal than this,” he says. “I’m in love with the people here.”

The camp, which today hosts some 35,000 displaced people, formed in 2014 when political conflict in the country’s capital fanned lingering ethnic tensions into open warfare. In Malakal, threatened members of the Shilluk, Nuer and Dinka tribes ran to the U.N. base. Haunted by the ghosts of the Rwandan genocide in 1994 that pitted ethnic groups against one another, local U.N. officials took in the fleeing people and posted peacekeeping troops to stand guard.

Bassano had been in Malakal for only two months when the war broke out. He had left Tanzania to join Solidarity with South Sudan, an international community of Catholic groups supporting teachers, health care workers and pastoral agents. Living in a teacher training college in Malakal, he was learning Arabic, visiting hospitals and working in a local parish.

When the shooting started, Bassano crouched on the floor of a bathroom, the best-protected room in the house, where three Catholic sisters also hid for safety. After four days of lying low, the priest and sisters made their way past burned vehicles and bullet-riddled bodies to the U.N. base.

Bassano was evacuated, but his heart remained in Malakal. After months of vicious fighting, he was finally able to return.

“All the priests in Malakal had left, so the people felt abandoned and forgotten. I decided to stay with them,” he says. It wasn’t safe to return to the town, and the teacher training college was in ruins. So Bassano lived with the displaced people who’d made a home on the U.N. base.

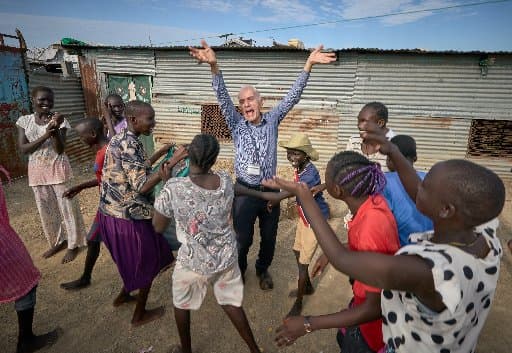

“I didn’t speak much Arabic, but some of them understood English. I stayed with them to show them that I, as a Maryknoll missioner, wanted to accompany them on their journey,” he says. “And they responded. They organized a youth group, dance and drama groups, and the catechists and Legion of Mary got to work. And with each of these groups, I pushed to include members of every ethnic group in the camp.”

Bassano talked U.N. officials into giving them a small parcel of land, where they started gathering under a plastic tarp for Mass. In 2015, they got a larger lot and constructed a building with sheets of metal roofing. The missioner calls it the “Tin Box” because, he says, it’s almost intolerable in the hot season.

Bassano admits his seminary classes didn’t include how to be a priest in a displacement camp. He invokes St. Daniel Comboni’s belief that mission will teach you both what to do and how to do it.

“Being in the camp has shown me that if we can come together, all the different ethnic groups, if we can be truly catholic with a small c, then we can find a path to peace, not just for people in the camp but for everyone in South Sudan,” he says.

Finding that path hasn’t been easy. In 2016, government soldiers invaded the camp, and armed Dinkas set fire to the shelters, burning over a third of the camp. At least 30 people died.

In the aftermath of the attack, Dinka residents of the camp moved back to the town. About the same time, the government started flying Dinka families from other areas to Malakal. They took up residence in the homes of the displaced Shilluk and Nuer living in the camp.

After several weeks, Bassano proposed that Catholics in the camp go into the town to celebrate Mass.

“There was a lot of resistance. They told me that if I went into town, I loved those people more than them,” he says. “But every time we gathered for worship in the camp, I reminded them we are one family of God. If we are truly Catholic, we have to reach out to our brothers and sisters in town.” Finally, a small group went into town, where Bassano celebrated Mass with the Dinka.

“That began a very small opening to reconciliation, despite the ongoing conflict,” he says.

“I’ve learned to be patient, to move with the people, to see what they’re feeling and thinking, and yet to encourage them that as true believers we have to put our divisions aside,” he says. “I’ve learned that when we’re simply present with people, by the example of our lives and our faith, by showing our concern for others, then something happens.”

Rhoda James Tiga, a Dinka woman who lives in the camp and works for the U.N., says Bassano helps people understand what it means to be Catholic.

“There is fighting outside — Dinka against Shilluk, Shilluk against Dinka, and the same with the Nuer — but inside the church, we all pray together,” she says. “Thanks to Father Michael, we are able to unite under the Catholic Church.”

Sergey Chumakov, a Ukrainian protection officer with the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, says Bassano has become a key player inside the camp.

“There is huge respect for him. People listen to him,” Chumakov says. “They see in him that South Sudan is not forgotten.”

Father Earnest Aduok, a Shilluk, who is pastor of St. Joseph’s Cathedral in the town, adds, “All the other priests who were here in Malakal were chased away. For Father Mike to stay in the camp has been a sign of hope.”

Today, in the wake of a wobbly 2018 cease-fire, the only camp that remains under the U.N.’s control is in Malakal.

“My hope is that the people in the camp can return home someday soon,” Bassano says. “I keep encouraging them not to lose hope. It may take five, 10 or 15 years, but we’ll get there. And I’ll accompany them in that journey as long as I can.”