WASHINGTON, D.C. — Pope Francis’ message for World Mission Day 2022 focuses on a phrase from the Acts of Apostles from the risen Jesus to his disciples just before his ascension into heaven.

“You shall receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you shall be my witnesses in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria and to the ends of the earth.”

It’s a phrase that aptly describes the mission work of Bishop Donald F. Lippert, a Capuchin Franciscan, who toils in a place some might consider the ends of the earth: the highlands of Papua New Guinea.

“The words ‘to the ends of the earth’ should challenge the disciples of Jesus in every age and impel them to press beyond familiar places in bearing witness to him,” the pope said in his message.

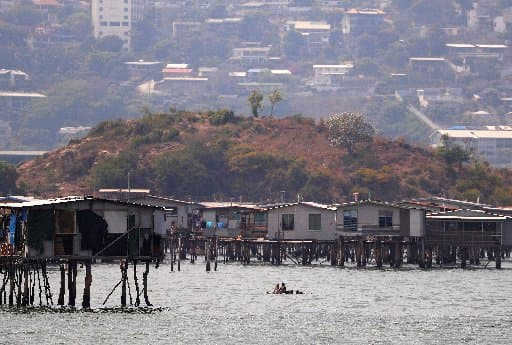

For Lippert, that place turned out to be part of an island swimming in the southwestern Pacific Ocean above Australia, which he pointed out on a map June 19, when he visited his old parish in Washington.

At the Shrine of the Sacred Heart, he spoke about the church’s work in Papua New Guinea, showed maps, photos of the majestic mountains, the smiling children and adults in the Diocese of Mendi, where he served for several years before being ordained bishop in 2012 by a fellow Capuchin Franciscan, Cardinal Seán P. O’Malley of Boston.

Lippert returned to Washington to see old friends but also to show several groups of Catholics in the U.S., through words and photos, some of what Pope Francis said in his message, that “no human reality is foreign to the concern of the disciples of Jesus in their mission.”

He told of how the first Capuchins arrived in the highlands where he ministers to serve in mission in 1955, how God is mentioned twice in the country’s national anthem, and of the country’s Blessed Peter To Rot, a fervent catechist who ran the local parish, opposed polygamy, still prevalent in the area, and defied restrictions of religious services during World War II when the Japanese occupied the region.

They are good people, with a great deal of simplicity, “who have accepted the Catholic faith with their heart, and they have a great deal of love for the Virgin Mary, they call her Mama Mary,” he said of his flock.

By his admission, their simplicity is sometimes a challenge to his Western mind and upbringing as a Pittsburgh-born Capuchin friar.

He offered the example of an exchange with a boy who asked him for a ball to play with.

“I said, ‘Do you want a basketball, a rugby ball or a volleyball?’ And he said to me ‘a round ball.'”

PNG, as many refer to it, he said, didn’t become a country until 1975. And its most remote area, the highlands, where he is, did not open to outsiders until about the 1950s, rapidly shifting from some traditional ways of the tribal people in the region to other Western influences.

Far from the politically inclined ideological divides and culture wars that permeate the U.S. church, Lippert faces challenges of his own.

Even a place that looks like paradise sees some violent tribal conflicts, as well as another issue that international organizations, including the church, have been trying to eradicate called “sorcery accusation related violence.” He explained that there’s a belief that “people don’t die. Rather, someone kills them.”

In many cases, said the bishop, women who are poor, elderly, who have no one to defend them, become the targets when they are accused of practicing sorcery, accused of causing the death of a particular person via sorcery, and in turn, they are physically attacked and sometimes killed by their communities, he explained.

“It’s the mentality of some people,” he said.

Puzzled by the account of violence against women and by the mention of polygamy, someone in the audience at Sacred Heart asked how a person goes about evangelizing, explaining what is right and wrong behavior.

“It’s the same challenge here,” Lippert said. “Just as Father Emilio (the pastor at Sacred Heart) is working to invite all to accept Christ with sincerity, to open up to an encounter with him, that’s what’s important. The rest will follow. The first and most important thing is that encounter with Jesus and it’s the same here. We’re all human beings, here and there, but we’re human beings with different histories. That’s what I’ve learned.”

Another person in the audience asked if he feared some of the dangerous situations in Papua New Guinea. He said there also were dangerous situations in Washington.

“There’s all kinds of dangers, natural dangers, too. Sometimes roads disappear during slides, but God protects us,” he said. “We do not fear.”

But it’s precisely in those kinds of places, the pope’s mission message said, that “Christ’s church will continue to ‘go forth’ toward new geographical, social and existential horizons, towards ‘borderline’ places and human situations, in order to bear witness to Christ and his love to men and women of every people, culture and social status.”

There is much to learn from all the worlds we inhabit, Lippert told the room of former parishioners, mostly immigrant Salvadorans who fled violent situations of their own — war, gang violence and poverty — and are now living in and around the nation’s capital.

“Everything there is kind of raw (in Papua New Guinea),” Lippert told them, speaking figuratively of social norms. “Everything here (in the U.S.) is cooked. … Here, it’s coated with so-called ‘culture.’ There, it’s all out there.”

He lives in two different worlds, he said. Sometimes there’s a certain interest that is often hidden, or not expressed, in places such as the U.S. But in his mission, he’s discovered a straight-forward manner, where there’s little room for interpretation, one not coated by self-interest.

“I’m challenged by the simplicity of the people very much,” he said of his flock in the Diocese of Mendi. “A lot of times, they don’t have all of these screens, ways of being deceitful, whatever. You know where they’re going. Their faith is a challenge to me, to be more simple, more direct.”

He was, however, direct in sharing how much he missed the large community of Salvadoran immigrants at the Shrine of the Sacred Heart, where served in the 1980s and 1990s and where many remember as him “Padre Donato.”

But he showed them how he managed to incorporate his love for the people of El Salvador in his new post on the other side of the world. His coat of arms features the episcopal motto: “Stap Wanbel Wantaim Sios,” in one of the English-based Creole languages. In English it means, “Be of one mind and one heart with the church.”

It was the episcopal motto of El Salvador’s St. Oscar Romero, the martyred archbishop of San Salvador.

“I left a piece of my heart at Sacred Heart,” he told them.