It’s one of our predictable public pieties: In the days just before and just after an election, the web fills with people saying how much they respect all those on the other side and their views.

The more contentious the election, the louder the declarations. Secular people tend to say that we’re all in this together, Christians appeal to a shared faith that stands above human politics. It’s all good feeling and tolerance and promises to be kinder in the future.

It’s a healthy reaction and corrective to months of political fighting. People fight about politics mostly like a bunch of guys in a bar who after several beers start fighting over the greatest player of all time. Rude things unrelated to the subject are said. Personal judgments are made.

Friends stop speaking to each other. Some expression of mutual respect is needed to restore the friendship.

But this public piety doesn’t help politically-engaged Catholics, and not just because public pieties are the talkative class’s equivalent of kitten videos. It’s only half-true at best. It expresses a hazy kind of good will, as public pieties always do, but it doesn’t express the way we do or should talk about politics as Catholics.

For one thing, no one actually believes it in the broad way they state it. Does anyone respect those of the extreme Right? Does any decent person respect the overt racist and misogynist, the anti-Semite, the social Darwinist, the person who makes selfishness a virtue? No.

We all assume these views express failures of character. Indeed, we don’t respect people who declare their respect for the extreme rightist, the racist, the misogynist, etc.

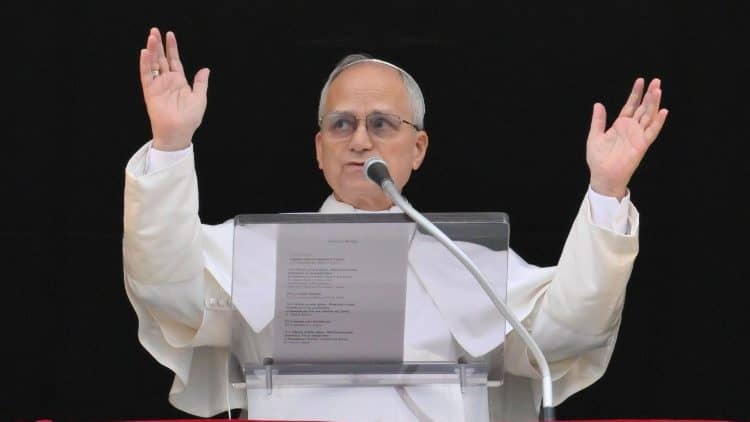

This election even support for the major candidates might fit. What some partisans said about their candidate, especially in defense of his or her indefensible statements, does not encourage trust in their political judgment. Do we respect, for example, a priest who uses the body of an aborted child as a political prop to get people to vote for his candidate?

And a lot of people don’t really mean it. They think they do, but they don’t really respect people on the other side. If they did, they would have treated their arguments more fairly.

Speaking for my own side, generally conservative Catholics who refused to support Trump, I almost never read a Catholic Trump partisan describe our position fairly. Some offered insulting judgments about our motives and others, though trying to be fair, still ascribed to us a really simple-minded position no one held.

In other words, people don’t really mean what they say when they say they respect the people on the other side. They think they do, and everyone feels good about saying it, but the piety hides from themselves as well as others their real commitments and their real way of addressing differences.

It’s like molasses poured over liver.

A Catholic approach begins with the truth. Who we really respect will be quickly apparent anyway. Politics requires many judgments: Whom do you trust? Whose character, motives, mind, and record do you accept as the basis for instruction and collaboration? Whom do you listen to, and whose writing do you commend to others? With whom will you work?

Who will be a comrade, who only an ally, and who, though you may love him like a brother, will be a political opponent?

The worst aspect of this public piety, however, is that it requires too little of us. At most, respect requires only assuming another’s sincerity. In practice it requires pretense. It doesn’t require engagement. “Respect” doesn’t found a serious politics or sustain a political community.

After this last year, there are people whose political opinions I cannot possibly take seriously. Their thinking was that bad. Some of them I know and like. I would trust them with my ATM card and the pin number. I would enjoy an evening in a pub with any of them, and some I would go to for personal counsel.

But we will not be political allies until they change radically. What I am doing almost every politically-engaged Catholic is doing, and many in the other direction, judging from comments people have made about me. And fair enough.

But then the primary Christian category for political exchange is not respect, but love.

Love requires a realistic view of the other, and a realistic view of yourself. It doesn’t make you pretend someone has made wise political judgments or is going to make wise political judgments. It doesn’t require you respect the racist or anti-semite or the partisan. It does require continued engagement, including turning the other cheek and walking the second mile.

Part of that realism means seeing them as people loved by God, who may love Him more than you do and may live a more virtuous life, who have other gifts than you, who see things you do not see. It means treating them as you would want to be treated.

I don’t want people to respect me as a political thinker if I’m talking rubbish. If I fell into anti-semitism, I would not want someone to tell me he respected me.

Progress is made not through good feeling but through often very painful honesty. The public piety might help a little, like the muttered half-apologies the guys make to each other the next time they meet at the bar.

As this election year has shown, our divisions even as Catholics run very deep. We can’t overcome them if we don’t face them.

David Mills is the editorial director of Ethika Politika www.ethikapolitika.org and writes weekly for Aleteia http://aleteia.org/author/david-mills/ .