[Editor’s note: This the first piece in a two-part essay by Charles Mercier. Part two will appear tomorrow.]

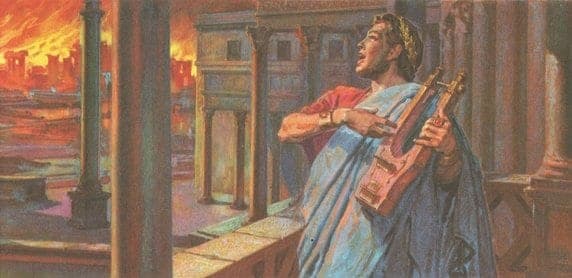

Did Nero persecute Christians? It’s part of our imaginative framework that the monstrous Roman emperor of 54-68 AD held Christians falsely responsible for the widespread fire in Rome in July 64, gruesomely executed them, and so inaugurated the Roman persecution.

A provocative article by Brent D. Shaw, a professor of ancient history at Princeton, late last year in Journal of Roman Studies, “The Myth of the Neronian Persecution,” argues plausibly that we should doubt that that actually happened.

It’s an issue for ancient historians, but also for Catholics who choose to think through the evidence in the spirit of faith’s compatibility with reason, particularly at a time when the notion of Christian martyrdom around the world is a pressing issue demanding clarity of thought.

The evidence is thin, to summarize Shaw, both for Nero’s persecution, and even for the possibility that Romans could so early have recognized Christians judicially or religiously as such. The persecution stands or falls on a single passage in the Annals of Tacitus, the Roman historian and imperial administrator, writing around 115 AD, some 50 years after the event:

“To get rid of the rumour [that he himself was responsible for the fire], Nero found and provided the defendants, and he afflicted with the most refined punishments those persons whom, hated for their shameful acts, the common people were accustomed to call ‘Chrestiani.’ The originator of this name, Christus, suffered (capital) punishment in the reign of Tiberius through the agency of the procurator Pontius Pilate.”

(That’s Shaw’s translation, leaving aside text critical issues.)

There is no evidence for where Tacitus got this, and no other ancient writer corroborates him. Suetonius, the Roman administrator and biographer, in a life of Nero roughly contemporary with the Annals, holds Nero alone responsible for the fire, narrates the fire without connection to Christians, and says Nero punished Christians only routinely, without mentioning the fire.

Cassius Dio after about 210 AD writes about the fire but says nothing about Christians. The Chronicle of Christian Sulpicius Severus (after 400 AD) depends entirely on Tacitus.

The first letter of Clement (leaving aside questions of authorship and date, but often taken to have been written in the 90s AD), has been precious to Catholics: it mentions a persecution of Christian “pillars” and of Christian wives and the names of Peter and Paul, but only obscurely.

The obscurity has been resolved by conflating the passage with Tacitus’s scenario to produce a more detailed story, but in truth 1 Clement makes no mention of a date for the persecution, Nero, or the fire. The context is not the history of the Roman church, but a condemnation of “jealousy and envy,” on account of which, it says, the victims were persecuted.

Lactantius, Latin father of the Church, in his apologetic On the death of the persecutors (318 AD), disregarded Tacitus while compiling instances of Roman tyranny against Christians. He included Nero’s persecution, mentioned Peter and Paul, but gave as cause the people’s abandonment of traditional cult, not the fire.

This is striking because, though Lactantius later tells how in 303 a fire at Nicomedia in Asia Minor, the eastern Roman capital before Constantinople, occasioned false accusation of responsibility and persecution by emperors Galerius and Diocletian, he declined to draw a natural parallel.

Tacitus then, Shaw says, provides unique witness to Nero’s post-fire Christian persecution. Was Tacitus wrong? He would be if in 64 AD the word “Christian” (a neologism combining the Greek word “Christos” with the Latin ending “-ianus”) had not yet been coined, or if Roman officials could not yet formulate “Christianity” as a religious or legal concept.

There is not much evidence that they could have. Tacitus would here be anachronistic, as he is occasionally, as, for example, in our passage when he calls Pontius Pilate “procurator,” the rank of the governor of Judea in Tacitus’s time, but not in Pilate’s, which was praefectus.

The word “Christian” first occurs in what we have of Latin writing shortly after the year 110 AD. The younger Pliny, as governor (legatus Augusti) of the province of Bithynia-Pontus on the Black Sea, in about the years 110-112, wrote his famous letter (10.96) asking the emperor Trajan for a ruling on Christians, admitting that he was unaware of legal precedent concerning them.

When he says, “I do not know the extent to which it is customary to punish Christians,” however formal and distanced his language, he appears ignorant of the accusation that they had set fire to Rome some fifty years earlier. This is curious for someone who for more than 20 years had had a distinguished career at the summit of imperial administration in Rome, at a time when fire damage was still being remembered and dealt with.

Pliny also seems unaware of a Christian persecution under Domitian (emperor from 81 to 96). Later Christians mentioned this persecution, which is sometimes taken as broad background to the book of Revelation, but there is little cogent evidence for it.

Before that, the word “Christian” had occurred only infrequently in the Greek New Testament, only in Acts of the Apostles and the first letter of Peter. In Acts, Christianity was earlier called “the way” and “Christians” could be called “Nazarenes.” According to Acts 11.26, the term “Christian” arose first in Antioch: the Roman-administered Greek east is an appropriate milieu for the invention of the word.

The word “Christian” could have appeared in a lost graffito in Pompeii, necessarily before 79 AD. But this is uncertain and even so would not in itself be evidence that a Roman emperor could understand that term already in 64, though it would indicate that the word had been coined. Bruce W. Longenecker has recently discussed the graffito and other evidence for Christians in Pompeii in The Crosses of Pompeii (2016).

The usage of 1 Peter 4.16, “if anyone suffers as Christian” is the first in Christian Greek to associate the word with legal hazard, one among other indications that the work may date to later in the century, after the lifetime of Peter. (Catholics pondering historical matters must understand that to consider pseudonymity in no way undermines the inspiration, inerrancy, or authority of a book of Scripture.)

Of course arguments like this become all too circular: 1 Peter is late because it uses “Christian” in a judiciary way, and its use of “Christian” is thereby excluded as early evidence for a judiciary meaning.

Ignatius, bishop of Antioch, writing letters in Greek on his way to execution in Rome, becomes the first person to identify himself by the word “Christian.” The year was about 110, the same time Pliny was deporting Christian Roman citizens to Rome from Bithynia.

In the end, Shaw demonstrates the scantiness of evidence that in 64 AD Christians in Rome were recognizable and despicable enough as a group that Nero could have targeted them. And when Pliny uses the word first in a Roman administrative document, it is exactly the time when the word is also first coming into use in other writers: 1 Peter (if dated critically after Peter’s lifetime), Ignatius, Suetonius, and Tacitus.

Such certain evidence as there is suggests that Tacitus’s portrayal of Nero’s attribution of “Christian” to a group in 64 is anachronistic.

One may, of course, object. There were followers of Jesus in Rome before 64; Paul wrote Romans to them. Nero could have punished them even if they were not yet called “Christians,” even ad hoc, if Roman law had not yet made provisions about them.

But then is sustaining a maliciously false accusation quite the same thing as being “persecuted”?

It is also true that Jews could be targeted, as they were by emperor Claudius for expulsion from Rome about 49 AD, perhaps for riots associated with disagreements with followers of Jesus. And Roman officials did not necessarily interest themselves in distinguishing Christians from Jews (as Gallio, proconsul of Roman Greece, in Acts 18).

There is a range of possibilities: If Tacitus is in fact anachronistic, is it only in the use of the word “Christian” for a group recognizable and despicable by another name? Is it in the notion that at the time followers of Jesus were recognizable at all, or distinguishable from Jews, to Roman authority?

Did Nero persecute Christians separately from the fire? Or is Tacitus doing justice to Nero’s mixed motives in finding a group recognizable enough to convict conveniently without caring to know anything accurate about them? The followers of Jesus may not have been recognized judicially as Christians, but neither perhaps were they condemned simply as arsonists.

Shaw concludes that it is plausible that Nero was blamed for the fire of 64 and found a minority to hold responsible and punish. Conspirators were easily identified among the vulnerable in Rome after fires whose cause was unknown: freedmen in 31 BC, debtors in 7 BC (and we don’t speak of their persecution).

Roman law often required punishment of ingenious cruelty. The victims burned as torches by Nero were evidently punished as arsonists, not Christians. When Tacitus says they were “crucibus adfixi,” there was not necessarily a Christian association: they were “stuck on stakes” in preparation for burning (leaving aside a serious textual problem). Those others dressed in skins and torn apart by dogs were punished with an appropriateness that escapes us.

The link between Nero, Christians, and the fire developed later, towards the end of the first century, Shaw says, at a time when Christians began to be recognized as such in Roman legal proceedings and there was developing a mythology of Nero, who, Elvis-like, had never died and had come improbably back to life as a destructive monster.

In the Christian version of the non-canonical Martyrdom and Ascension of Isaiah (late first century AD), Nero is the anti-Christ ushering in the end of the world. In canonical Revelation, of course, Nero appears as the beast whose number is 666. Tacitus himself narrates a false Nero in Histories 2. Nero’s reputation as the first persecutor of Christians emerged in this atmosphere.

The Histories were written a few years before the Annals, by about 110, and Tacitus had there discussed Judea without mentioning Christianity. Pliny sponsored Suetonius, who likely was on his staff in Bithynia. Pliny and Tacitus were friends. Tacitus’s term as proconsul of Roman eastern Asia Minor 112-3 could have overlapped with Pliny’s term in Bithynia.

So it may be that Christianity and its legality were first coming to this close group’s attention at the same time and in the same part of the world. That new knowledge Tacitus would have supplied, Shaw argues, anachronistically to his telling of the fire.

This the first of a two part article. Next: If Nero didn’t persecute Christians, what then?