A few years ago I was struck by an ad on the London underground sponsored by the organization Age UK, which seeks “to provide companionship, advice, and support for the millions of people facing later life alone.” The ad included the following verse:

No one to say good morning to.

No one to bless you when you sneeze.

No one to take tea with. Or whisky, for that matter.

No one on the end of the phone.

No one to share anything with: a cake, a laugh, or a problem.

No one to make one day any different from the last.

No one to turn to.

No one, but no one, should have no one.

Along with being impressed by the efforts to raise greater awareness of the UK’s neglected elderly population, there was a certain irony at play here. While this group’s ad campaign was being rolled out throughout the country, a bill to legalize physician-assisted suicide was being debated in the British Parliament.

The bill was eventually defeated, but as we’ve witnessed here in the U.S., the campaign for physician-assisted suicide continues to spread throughout our country and much of the Western world. The vast majority of suicides are related to depression or other mental disorders—treatable ones at that—and loneliness or fear of being a burden, particularly among the elderly, continues to be a significant reason why folks seek doctor-assisted suicide.

The practice of physician-assisted suicide represents society’s failure to provide the love and adequate care to ensure that the suffering and dying are given the support they need. Shamefully, it also provides an easy excuse for us to avoid promoting better care options for those that are dying and it limits our ability to think critically about the dying process itself.

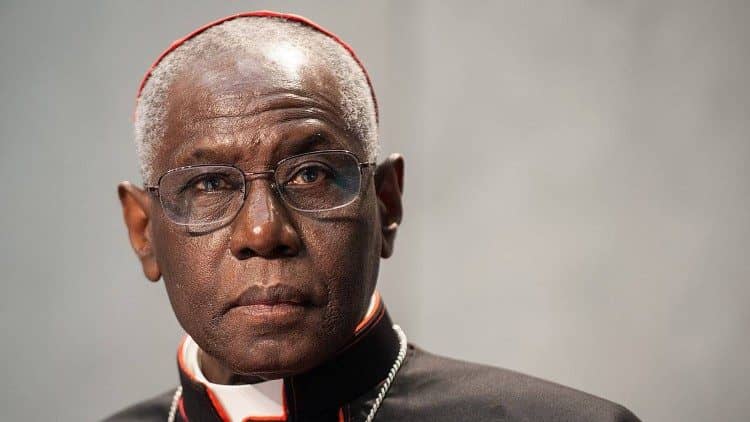

In 2012 — days after Massachusetts citizens defeated a bill that would have legalized the practice in their state — Cardinal Sean O’Malley of the Archdiocese of Boston used the occasion to issue a clarion call for the Church to do more to support those that are facing death:

“We are all called to work for a more just society where the weak and the vulnerable are nurtured and protected…Patients are best served when the medical establishment, families and loved ones provide support and care with dignity and respect. We will be judged by how we treat those who are ill and the infirm. They need our care and protection, not lethal drugs. Let us work together to build a civilization of love – a love which is stronger than death,” he declared.

To that effect, the Catholic Church of England and Wales has just launched an impressive initiative—“The Art of Dying Well”—with the aim of “providing hopeful accompaniment for the human journey.” This effort is multi-faceted and provides resources for those facing death and those confronting the death of a loved one, while also attempting to open up a broader public conversation about what it means to die well.

And while it’s specifically Catholic, its resources are open to people of all faith and none (which should be a hallmark of any Catholic ministry).

In facilitating a conversation about dying well, this effort addresses both the practical concerns of one’s last days, such as medical treatment desires, alongside spiritual matters. The website also includes an animated video (narrated by the English actress Vanessa Redgrave) of the fictional Ferguson family facing the last days and death of the family patriarch.

In doing so, “The Art of Dying Well” helps shift the focus to one’s life rather than one’s death and does so in the spirit of hope rather than despair. Most importantly, efforts such as this one provide concrete ways in which we can change the narrative around dying—particularly when it comes to combating the way it is generally presented in our public arenas.

During the 2012 election cycle, the Obama campaign released “The Life of Julia”—an online tool that illustrated the practical ways in which the Obama administration’s policies would benefit an average middle class woman named Julia over the course of her lifetime. The video was both lauded and mocked, but it ultimately proved useful in moving the conversation from mere policy debates to real-life personal experiences.

Similarly, in 2014, the story of Brittany Maynard—a 29-year-old woman from California who after being diagnosed with brain cancer moved to Oregon to take advantage of its legalized physician-assisted suicide law—went viral after People magazine released a video of her sharing her story and advocating for assisted suicide.

Maynard went on to make the decision to end her own life—and her story changed the face of the assisted suicide movement and was consequential in California legalizing the practice a year later.

These two examples should remind us of the importance of stories. If we are to have any hope in shifting public conversation and changing the debates over the ethics at the edges of life in a different direction, Catholics must become better storytellers. If we truly believe that our vision of the human person and society is really attractive, then let’s illustrate it.

Christ certainly did this in the gospels through his frequent use of parables. St. Francis of Assisi affirmed this when he encouraged us to preach the gospel and when necessary use words.

Pope Francis offers a master class in this during his weekly audiences when he spends more of his time interacting with the public and demonstrating what Christian witness means than he does by simply preaching about it.

As the ad on the London Tube stated so succinctly: “No one, but no one, should have no one.” In many respects, that’s the Catholic vision for the world in a nutshell. If we really believe this to be true, let’s redirect our energies to do a better job of actually showing this truth rather than just talking about it.