[Editor’s Note: The Jesuit-run journal La Civiltà Cattolica, reviewed by the Vatican’s Secretariat of State prior to publication, recently carried an article by two close friends of Pope Francis arguing that an “ecumenism of hate” between ‘Evangelical fundamentalists’ and ‘Catholic Integralists’ is gaining power in the United States. Given the significance of the article in Vatican-U.S. relations, Crux will be publishing a series of reactions to the piece.]

In the last fifteen years, people in the pews have grown to expect adult conversations about man-made problems within the Church, especially those presenting a threat to the Church and society. One such challenge is the division within the Church along political lines. This is no secret to anyone paying attention, although too often it is hidden in plain sight.

The division is deep, and weakens the Church at a time when the Church could be – and arguably should be – providing leadership and serving to bridge the divides within our society and the global community. This is the role that Pope Francis, the bridge builder, envisions for the Church in today’s world.

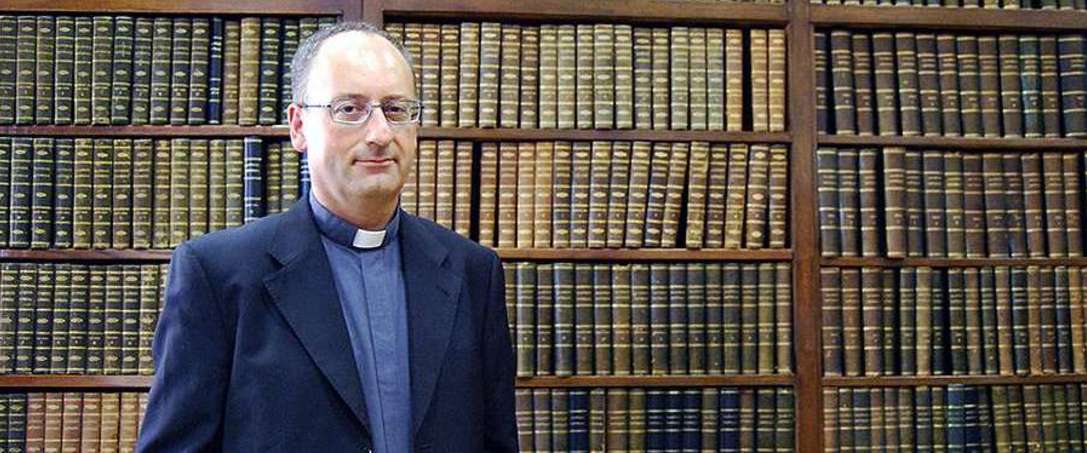

Recently two intrepid souls, both of whom reportedly hold Pope Francis’s confidence, sought to advance a long-overdue conversation on this matter. They’re Jesuit Father Antonio Spadaro, editor–in–chief of the Jesuit publication La Civilità Cattolica, and Presbyterian Rev. Marcelo Figueroa, editor–in–chief of the Argentinean edition of L’Osservatore Romano.

They co-authored an essay entitled, “Evangelical Fundamentalism and Catholic Integralism in the USA: A Surprising Ecumenism,” published in La Civilta Cattolica. In it, the authors lift the veil on the dark side of the decades-old ecumenical accord between conservative Evangelicals and Catholics in the United States. They correctly observe, I believe, that it has metastasized into an unholy alliance yielding the bad fruit of an “ecumenism of hate” – particularly with respect to “its xenophobic and Islamophobic vision that wants walls and purifying deportations.”

At the heart of the piece is a phenomenon they observe – “a desire for religious influence in the political sphere” — which unwittingly distorts, at best, or deliberately manipulates, at worst, religious values to achieve a political end. They also argue that this has its roots in Evangelical fundamentalism.

In a follow-up interview, Spadaro explains that, “Our attention focused on phenomena that have degenerated and are based on values that seem to be evangelical but in fact are ideological. We refer to those that form what we call ‘the ecumenism of hate’ in its various expressions.”

The piece has stirred tremendous controversy, and the authors have come under attack primarily from the Catholic right. While many of these critics deny that the alliance has spun out of control, the focus of their critiques is on the style and organization of the essay and what they allege is misconstrued historical context.

RELATED: ‘Ecumenism of hate’ unjustly defames real Catholic/Evangelical dialogue

These critics miss the key point, and the accompanying risks to our faith and pluralistic democracy presented by the authors — not the least of which is that to “[confuse] spiritual power with temporal power means subjecting one to the other.”

I am not an expert in Protestant history. However, I know what I see and hear every day. Below are four points in support of the authors’ arguments.

- There’s an Evangelical/Catholic alliance that has evolved over time and was first codified in 1994 with the signing of ”Evangelicals and Catholics Together.” In 2004, the New York Times reported that, “Catholic and evangelical leaders who forged relationships in the anti–abortion movement… are now working side by side in campaigns on other culture war issues, and for Republican candidates.”

- As it has evolved, the nature of the alliance has changed from one of shared interests – including as the authors present “…around such themes as abortion, same–sex marriage, [and] religious education in schools” – to a shared “Manichaean” worldview that “divides reality between absolute Good and absolute Evil.” It goes without saying that such a worldview is anathema to the inherent “both/and” perspective of Catholic thought, and the imperative within the Catholic social justice tradition to bring both faith and reason to bear on the moral issues of our time. Again, from the New York Times in 2004, “Though miles apart on salvation, they find common ground in the language of moral absolutes.”

- In 2009, the alliance came of age when 54 U.S. Catholic Bishops signed the “Manhattan Declaration,” a conservative religious manifesto, authored by three notable Republicans, which is a call to “Christian conscience” on the issues of religious liberty, the sanctity of life, and marriage. The bishops were among approximately 160-plus U.S. bishops who, between 2004 and 2012, made public statements effectively saying that you cannot be a “good Catholic” if you vote for the Democratic candidate. Some also politicized the Eucharist.

- Critics have also dismissed the author’s use of the comparatively well-trafficked website Church Militant as an example of “political ultraconservatism.” They say that it is an invalid, extreme case, when actually it is a valid example that is extreme but not isolated. Seek and you shall find. A cursory review of the Catholic website EWTN on July 30th, the largest religious media organization in the world, shows the following headlines in scrolling graphics on their homepage: “Battle Ready” (with an image of a Crusader in armor); “Reality Check, The Last Four Things: Death, Judgment, Heaven, Hell”; and, “EWTN’s Warrior’s Rosary – A Must Have for Every Spiritual Warrior”. This is one Catholic-right media outlet. There are literally dozens more with similar content, which collectively reinforce one another.

RELATED: A note on the ‘ecumenism of hate’ and papal rhetoric

Spadaro and Figueroa also offer a diagnosis that “… underlies the persuasive temptation for a spurious alliance between politics and religious fundamentalism” – meaning, fear. They go on to say, “It is fear of the breakup of a constructed order and the fear of chaos….Religion at this point becomes a guarantor of order and a political part would incarnate its needs.”

Ironically, one critic of their piece, Austin Ruse, a member of the Council of National Policy that Spadaro and Figueroa call out, provides more evidence of their assertions in a rebuttal to it. In it, Ruse says that Evangelicals and Catholics are “…banding together to fight against what can only be described as the new state religion, the new state god….It is a call in the present fight to put aside our arguments about religion, and fight together against a common foe who is coming for us all.”

Our Church should be leaven for the world and we should be leaven for one another, each on our own spiritual journey, regardless of political affiliation. Our faith is meant to be practiced in community. When we receive Communion, we receive it as sisters and brothers in Christ, not as a member of a political party.

I must confess that I am challenged to reconcile my Christian beliefs to those on the right who hold the views that Spadaro and Figueroa describe. Yet, I also believe that it is incumbent upon all of us to seek that understanding. I believe the vitality of our Church depends on it today, and that our society can certainly use the best of what our faith has to offer.

A refrain of Pope Francis is to engage in the “culture of encounter.” He says, “For me this word is very important. Encounter with others. Why? Because faith is an encounter with Jesus, and we must do what Jesus does: encounter others.”

Perhaps all Catholics, Evangelicals and other Christians, can agree that we must – or at least must try – to do what Jesus does. Perhaps our Church – from the laity to the bishops, and from our parishes to our Catholic colleges – can begin to reflect on how we can cultivate a culture of encounter within our faith.

Spadaro and Figueroa have opened the door for us to have this long overdue conversation.

Steven A. Krueger is the president of Catholic Democrats, an advocacy organization whose mission is to advance the Catholic social justice tradition in the public square and within the Democratic Party.