SIUNA, Nicaragua – In a rural area where a priest might spend hours to get to any one of 750 small communities and 15 parishes, there’s a tall, white figure who, driving his white truck and wearing his Birkenstock sandals, seems out of place.

Yet he finds himself perfectly at home working from a small office that resembles a closet in size, sleeping in a room that has little more than a bed and an anti-mosquito net. His backpack sits on the floor, next to the bed, forever ready to go.

Bishop David Zywiec, a Chicago-born American of Polish descent tapped by Pope Francis in Nov. 2017 to lead the youngest diocese of Central America, is a 71-year old Capuchin Franciscan who’s spent most of his life as a missionary in the region.

He arrived in Nicaragua in 1975, when the nation was ruled by Luis Somoza, son of Anastasio Somoza, and the heir of a dynasty that ruled over the country for six decades.

Zywiec “arrived by land” on the night of Jan. 3 in Managua, the country’s capital, he recalled, and his welcome was a premonition of challenges that would lie ahead: A week before, during a Christmas celebration, the Sandinistas, who were trying to take over the country, had kidnapped some members of the government leading Somoza to institute a curfew.

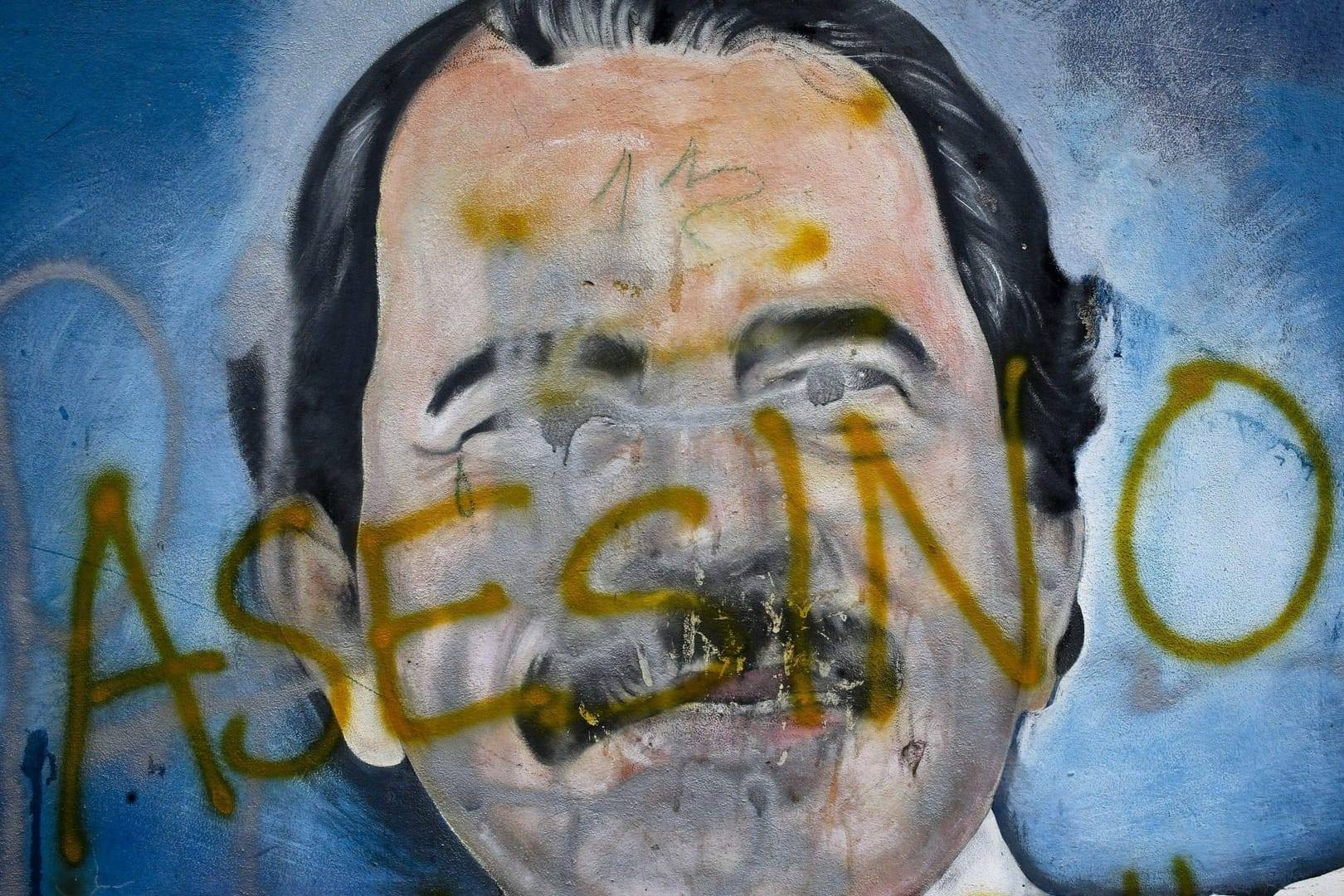

Over four decades later, some would argue not much has changed in Nicaragua. There’s a youth-led movement trying to bring down the government of Daniel Ortega, who, with his party, the Sandinista National Liberation Front, brought down Somoza, and once again people are taking sides.

Zywiec is cautious with his words, acknowledging that things are worse than they should be, but that he has a divided faithful and clergy, many of whom support Ortega and many of whom don’t.

“Look at the 12 apostles,” he said, as a way of explaining the situation. “Jesus chose a man who was the tax collector for the Roman empire and also one who was an enemy of Caesar. But Jesus is bigger than politics, and the same happens here.”

As one of the men working with the bishop told Crux, Zywiec has had to learn to make his peace with the government, knowing that “who’s up today could be down tomorrow and vice-versa.”

Instead of fostering division, Zywiec focuses on being a minister to his people, what Pope Francis would call a “shepherd with the smell of his sheep.”

Ordained a priest in June 1974, Zywiec spent his first two years in Nicaragua in Siuna, where it can take a priest more than 24 hours to reach one of the 750 small Catholic communities – using a car, a mule and then a boat to get there. He was in charge of 60 communities at the time.

During those first years, he saw how the Somoza regime hunted down Sandinistas in the jungle in which he was trying to minister.

“A lot of people were killed or disappeared,” he said.

He doesn’t say it, but according to many the same thing is happening today. Siuna, however, remains a stronghold of the Ortega regime, and the relationship between the bishop and the mayor, a member of the ruling party, are good. As a matter of fact, the mayor helped the church secure a lot on which a 10,000 square foot cathedral can be built.

The mammoth project has an estimated cost of $1.5 million, and between the cooperation of the local parishes and foreign aid, including the U.S.-based Papal Foundation, the pontifical foundation Aid to the Church in Need and even the U.S. bishops’ conference, they’ve raised a little over half what is needed.

Each of the parishes sends workers to help build the cathedral, with some 25 men working there on any given day for two weeks at a time. Most materials to build the walls and red roof have already been bought, which is the first stage. Furnishings will have to wait until the rest of the money is raised.

Zywiec returned to Siuna in 2017 after spending close to a decade in Costa Rica in the 1980s, taking a six-month sabbatical in the University of Notre Dame and serving for two years in an inner-city parish in Chicago. He’s been back in Nicaragua for the past two decades, helping in what used to be the even more dispersed diocese of Bluefields.

Ordained a bishop in 2002, together with his boss, American Capuchin Pablo Ervin Schmitz Simon, they presented a plan to the Vatican three years ago to subdivide the diocese into three, but they had to settle for two.

Asked if he feared for his life when he first arrived back in 1974, he said that he didn’t, though he questioned the actions of the government: “You’re supposed to be innocent until proven guilty, right? Not here, not then.”

At the time, he gave his bishop a list with 200 people from his communities who’d gone missing, and the prelate decided to transfer Zywiec to Bluefields before he joined the list.

Despite his bishop’s reservations, Zywiec told Crux he never had problems with the people, though he did have some with the American embassy. Back then, the U.S. was using missionaries to gather intelligence, and he refused to provide it, at a moment in which the area he was working in was being bombed by American forces.

“I told them that my parents were tax-paying Americans, and that it would be ironic if they ended up paying for the bombs that killed their son when he was working as a missionary in the Nicaraguan jungle,” he recalls telling the embassy.

After that, he’d have bi-annual meetings with a man from the CIA whom he recalls dubbing “Slippery Jack.”

“I was expecting for the American government to help me, but they didn’t,” he said. After four years in Bluefields, he went to Costa Rica, but he got “burned out” because they have “enough priests in the Switzerland of Central America.”

At the time, Costa Rica was the only country in Central America not engaged in civil war or internal armed conflict: It’s army was even abolished in 1949, and the country has lived without a military ever since.

When they were appointed to Bluefields, Schmitz took care of running the diocese while Zywiec focused on the communities in the northern region, where Siuna is. Today, he said, learning how to do the administrative side of things is part of his “pastoral conversion.”

With a humble, handmade wooden cross tied with a blue string, Zywiec is far from your usual bishop. He’s seen it all, both as a local and a foreigner. He’s earned the respect of the flock he leads, including the priests who call him by his given name, David, but who are quick to do as he asks.

Though not heavily populated – All of Nicaragua has just six million people – the diocese of Siuna is geographically as big as the Netherlands.

There’s an estimated half-million people, 70 percent of whom are Catholic. Many live on a dollar a day, but despite the challenging situation, Siuna is considered a safe place and one which remained mostly on the sidelines of a civil uprising that began in April. Most credit the bishop for it, who, seeing the division it would cause in his diocese, convinced both sides of the need for an honest dialogue where the needs of the people were put ahead of the “passions of each one,” a driver told Crux on Nov. 22.

The driver requested to remain unnamed to guarantee that the understanding forged by all those involved, many of whom are part of the diocesan team, himself included, stays intact.

“The crisis is taking its toll on Nicaragua,” he said, using as an example the fact that the paving of a road that was supposed to connect with a series of surrounding towns has been suspended since April.

“Monsignor has taught us not to add to it by talking more than we need to,” he said.

People in the region live mostly off farming and cattle. Before the crisis, some 80 trucks full of cattle would leave every day for Managua; today, only 8 do so. A medical clinic that used to see 40 patients a day before April today sees an average of 15, because people can’t afford the $1.50 to pay for the visit to the doctor.

The territory is uneven and mountainous, at the shore of an artificial lake that was created by the mining industry, and has a long rainy season that makes the city resemble an Indiana Jones movie set.

The difference is that Siuna is not lost nor abandoned, simply poor and resilient, led by a bishop who, four years from retirement, is still going strong.