GRANADA, Nicaragua – Even though an estimated 70 percent of Nicaragua’s six million people are Catholics, many in the country today nevertheless believe that being Catholic and young is virtually synonymous with being a criminal, or, at the very least, a potential enemy of the state.

This helps explain why of the 10,000 young people who were hoping to go to Panama for World Youth Day from the diocese of Granada, an hour by car from the capital of Managua, only 1,000 of them will attend.

In the city of Juigalpa alone, some 300 young people were planning on attending, but now only 70 will do so thanks to a grant from Aid to the Church in Need, a pontifical foundation headquartered in Germany that helps the persecuted Church.

Several of those young people spoke with Crux Nov. 18-19, asking to remain anonymous and refusing to allow their conversations to be recorded, so no electronic trace could be used by government authorities to identify them.

For the purpose of telling their stories, the two young people from Granada will be named “Brian” and “Carmen” and the two from the diocese of Juigalpa, further south from Managua, will be identified as “Daian” and “Isabel.”

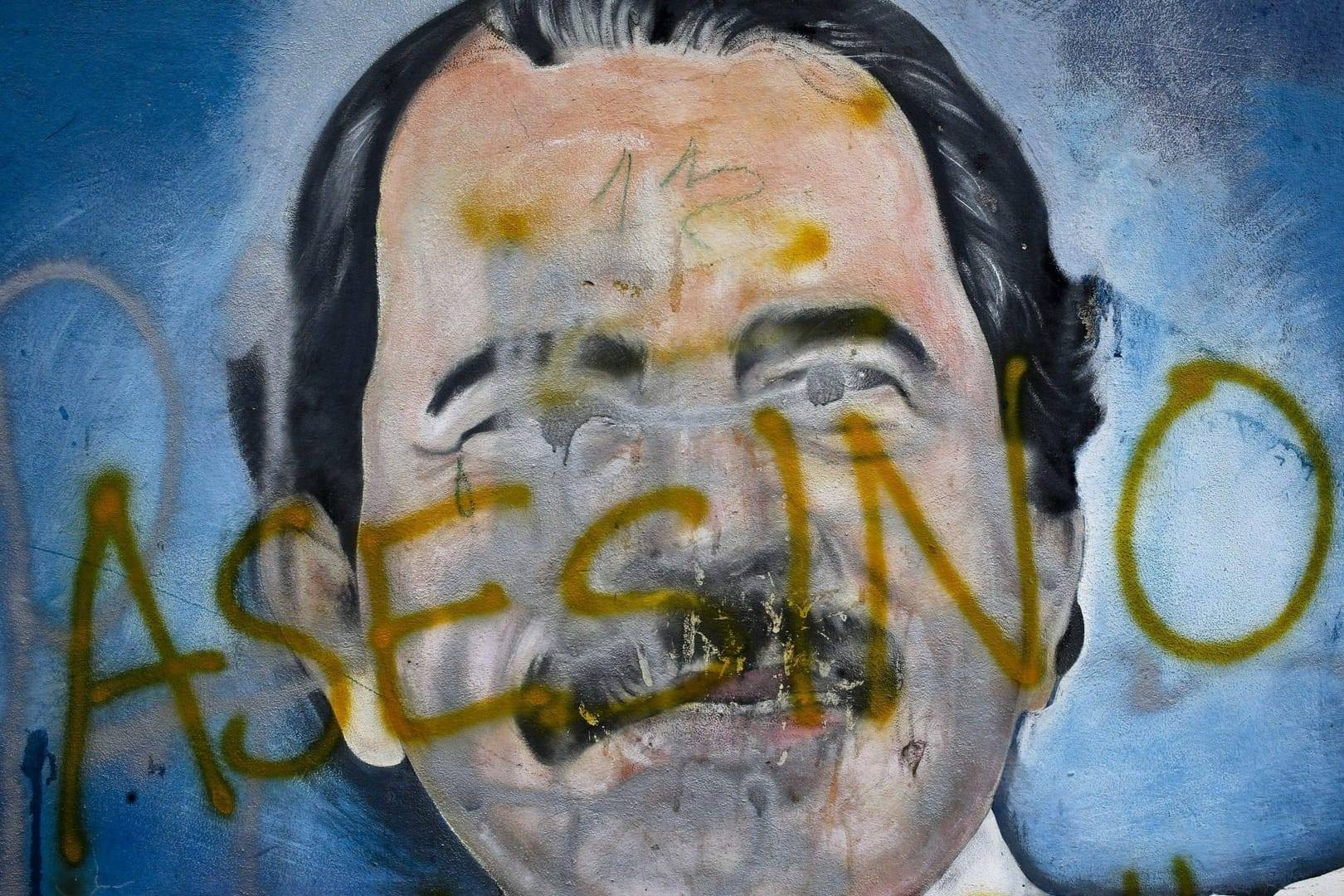

All are in their 20s, and even though none opted to bring it up themselves, they were among the Nicaraguan youth who, in the words of Managua’s Auxiliary Bishop Silvio Jose Baez, “woke the conscience of the nation” by rising up against the national government of President Daniel Ortega and Vice President Rosario Murillo, his wife, in April.

Most of the time now, Brian and Carmen remain in hiding and agreed to do the interview at the request of a parish priest they trust. The government sees such youth as its enemy, one of them said, but for the young people who took to the streets, the Church was an ally.

“It’s a crime to be a Catholic young person today,” said Bishop Jorge Solorzano, in a phrase that was repeated over and over during the four days Crux spent moving up and down the diocese of Granada with a delegation from Aid to the Church in Need.

Solorzano is responsible for the country’s youth ministry, and he can’t hide his disappointment that of the 10,000 who were going from his diocese, only 10 percent are now expected to make the pilgrimage to Panama to attend a gathering of hundreds of thousands of young people from around the world with Pope Francis.

Nicaragua was set to host an event known as “days in the diocese,” with some 15,000 young people already registered to visit the country for a missionary week before heading to Panama. Yet due to the violence that ignited in April, the bishops decided it wasn’t safe.

Isabel was helping organize the days in the Diocese in Juigalpa, and said she was heartbroken when the bishops announced the pilgrims will no longer arrive.

“We were already in touch with delegations from Germany, Switzerland, Brazil …” she said. “We had a plan of what we wanted to show them, do with them. Families were coming to us saying they were ready to host the pilgrims. A woman even told us she was building an extra bedroom in her home just for that!”

“But God has his plans, and he knows why this is happening to us right now,” she said.

The disappointment was generalized, and the young people weren’t the only ones heartbroken with the bishops’ decision – a decision supported by the Vatican Dicastery for Laity, Family and Life, that co-sponsors World Youth Day.

The priest who heads the diocese’s youth ministry, who also requested anonymity because he’s been “blacklisted” by the government, said the situation was disappointing because they’d already put in many hours of work to guarantee that pilgrims felt at home, with some young people even learning other languages.

Juigalpa was heavily affected by the April unrest, and one of two parish churches the priest oversees was just two blocks away from what locals call tranques, the Spanish word for roadblock. Young people set them up on the main roads to try to keep police and paramilitary forces out of the city.

At the request of the young people, the priest went to the tranque one day just as pro-government forces began shooting.

“We were caught in the middle,” he said. “People thought it’d be safe to walk with us, as we were clearly identified as priests, and they thought the police wouldn’t shoot. But they did. So when I turned around to make sure everyone was safe, I realized that we six priests were once again alone.”

Bishop Rene Socrates Sandigo Jiron decided the situation was too dangerous and ordered the priest to close his parish, then snuck him out of the city for a while: “I don’t want a martyr, I want a priest!” Sandigo said.

Despite the challenges, including the possibility of being stopped by the Nicaraguan army at the border, all four young people plan to attend World Youth Day – and come back.

Sandigo, they said, was adamant: “No one is staying behind.”

He’s already lost too many young people from the diocese, he told Crux, who have been forced to go into hiding.

“This was a very tough, sad year,” he said. “Young people were divided among those who support the government and those who don’t, so there were a lot of clashes among people who’ve been friends for a lifetime.”

“But we have hopes for 2019, it’s going to be a better year, and World Youth Day is a good way to begin it,” he said.

Several people consulted by Crux agree that young people today are being “hunted down” for having participated in the rallies, and despite the massive numbers, the regime has identified them.

An estimated 500 are in prison, a similar number died as a result of the protests and an unknown number of young people remain missing, with some estimates putting the number at close to a thousand. In addition, thousands have gone into exile, and those who can’t afford to travel abroad, are currently in hiding.

A second priest from Juigalpa who spoke with Crux reported that, even though he agrees with the ideals of the young people, not all protesters were peaceful, and many had home-made explosives that could have done a lot of damage.

“But these were kids, with no experience, and no memory of what we lived through in the 1980s,” he said, referring to the civil war. “That’s not to say the government didn’t respond in a disproportionate way.”

Bernard Robles, a 25-year old deacon who was later ordained a priest by Solorzano on Dec. 8, feast of the Immaculate Conception of Mary, told Crux that he was not afraid to be ordained, despite the tumultuous situation the country is experiencing, and in particular, the persecution the Church has been a target of.

“I’m moved by the example of Christ who gave his life, without asking for anything in return,” he said. “I’m not afraid to be ordained because of the situation of persecution the Church is living in this country, the injustice the nation is living, with all the goods in the hands of a few. On the contrary, I see it as an honor to be ordained in this moment, it will be historic.”

He was ordained a deacon on June 29, while the seminary and his city were cut off by barricades protesting the government, so he was afraid people wouldn’t make it.

“I realized at that moment that being a priest means giving myself in full,” he said. “Being ordained in these difficult times makes me think of St. John Paul II, who was ordained in hiding under the Nazi regime. I’m far from being a saint, but I do believe that saying ‘yes’ to Christ when everything is fine is easy. To say ‘yes’ now is more of a challenge, and I think that I’m ready for it.”

Father Oscar Cruz Zacarias, of the parish of St. Raphael – one of 20 that have been created in the past eight years to tend to the needs of the growing local community – said that the situation in Nicaragua today is “very difficult.”

Many of those in his community lived off the tourism industry, but with the country paralyzed, foreigners are no longer coming, so people have been laid off.

In addition, many of the young people in his church have had to flee, afraid of being caught by the regime, and his own faithful are divided between those who support Ortega and those who don’t. Many, he said, have stopped attending church because they believe the priests and the bishops betrayed them by protecting the protesters.

In July, together with seven other priests of the southern region of Granada, he found out that there was going to be a clash between the paramilitary and some 50 young people who had barricaded one of the country’s main roads, stopping traffic some two miles from his parish.

They decided to go, with the Blessed Sacrament, to try to stop what he believed would have been a “bloodbath.”

“When they saw us coming, the paramilitary got back in their trucks and ran away,” he said. That experience convinced him of the fact that there’s something evil at work in Nicaragua that goes beyond corrupt and angry men, because the reaction they showed to the Blessed Sacrament was “disproportionate, they were running away from Christ.”

In the words of a local religious sister who asked to remain unnamed, Ortega wants to make the people believe everything is back to normal, but “nothing is. If it were, would people go to work to never be heard of again?”

She’s convinced what the people want is for Ortega to call elections, but she acknowledges that the challenge is finding an alternative since there’s no opposition to speak of, at least not one, she said, which could win elections fair and square.

The further the situation goes on, the harder it appears for young people.

“The future of each one of us is in the hands of the Lord,” Brian said. “We’ve gone through some very difficult times, many of my friends are no longer here, or they have gone missing. We need for young people from around the world to pray for us.”

Carmen agreed: “We are afraid. We can’t deny it. But we know that faith can move mountains, and we trust that if young people from around the world can come together and pray for us, then maybe there’s hope for us.”