MATAGALPA, Nicaragua — “You’ve come at a hard time … the people are suffering, because they’re afraid to go out in the streets,” said a priest in Matagalpa, Nicaragua, to a group of visiting charity workers and a Crux reporter over a mid-November breakfast at the bishop’s residence downtown.

Despite municipal signs promoting Matagalpa as “Christian, socialist, charitable,” tension was palpable in the streets, with policemen and anti-riot forces trying to stop a rally for peace that local women have organized for the past 20 years to honor those killed in the country’s bloody civil war.

Yet public rallies have been banned in Nicaragua since July, unless you’re a state worker, in which case you’re paid to spend your afternoons “protesting” by showing support for the government in the town square or the roundabouts.

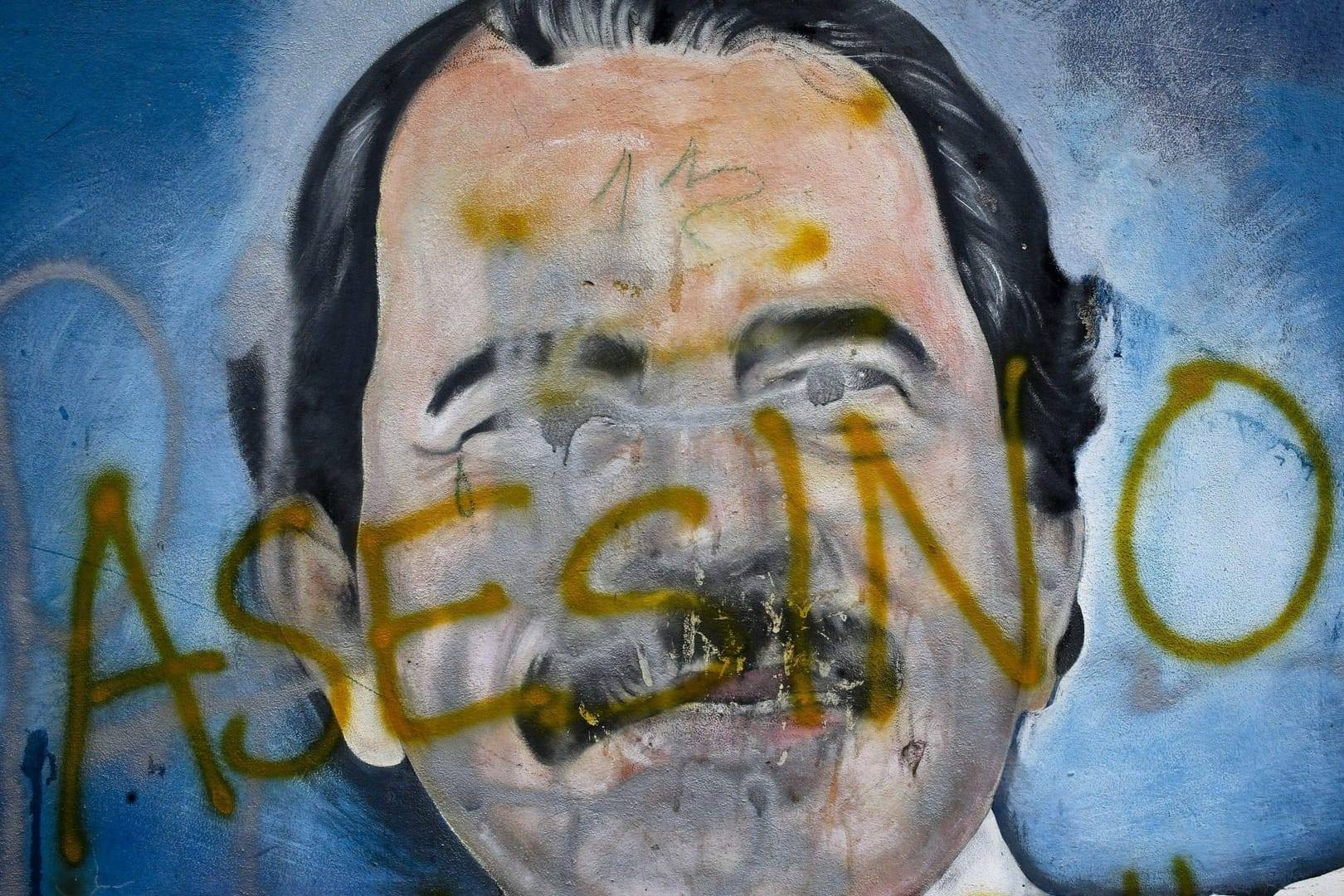

For safety reasons, the priest speaking to Crux never disclosed his full name at the suggestion of his bishop, Rolando Alvarez. He will be identified as “Brian.” No photographs were taken of the meeting nor was the conversation recorded, as the priest is one of many who’ve been targeted by the government of Daniel Ortega and his wife Rosario Murillo since protests first flared up in April.

“I’m lucky, other priests have had to flee the country,” Brian said. An estimated 30,000 Nicaraguans in all have left the nation since April.

Crux spent much of Nov. 23 with the bishop, visiting the local seminary, a church in nearby Sebaco that had been at the center of the violence, a house of the papal charity Caritas that was burned by pro-government forces, and other key places in the diocese.

Along the way, Alvarez would be stopped by people who wanted a picture with him, but also by middle-age men driving trucks calling him a golpista, meaning coup-organizer, and several other choice terms that can’t be quoted here.

According to news reports, on the day before we met, members of the national police went to the local School Republica Argentina and ordered students at gunpoint to express support for the government.

“They [the Ortegas] want to take it all, and they’re not afraid,” Brian said. “They’ve been like this since 2006, when they were elected, but they’ve gotten bolder and more open in their interest to quiet voices that dare to oppose them.”

Since the havoc began on April 18, Brian said, his ministry has taken “a new path,” because it’s hard to remain unchanged when people interrupt a Sunday Mass saying they’re being persecuted or killed.

“They weren’t throwing candy at them, no… they were aiming for their heads, their necks and their chest. They were trained to kill,” Brian said of the pro-government forces.

“The Gospel leads us to open the doors to those who are persecuted, and that is what we’ve done,” he said. “Our churches have become shelters, not houses of planning, as the government is trying to portray.”

The order the local doctors had received was not to treat any patients who came in after the protests, “to let them die. How could we remain with our arms crossed, doing nothing?”

On April 24, together with other priests, he helped free 200 young people who were besieged by the police and members of the army wearing civilian clothes.

“It’s become evident that the government is capable of doing anything, but the Gospel teaches us to be with the people,” he said.

Some weeks later, on May 15, what the priest defined as a “massacre” unfolded, with government forces firing AK-47s and 12-calibre shotguns at young people with only stones and fireworks used in patronal feasts.

“I went to the chief of police to try to stop the bloodbath, but he told me to ‘move away, it’s not your problem’,” he said. “But how could it not be? People were getting killed!”

He grabbed a car that belongs to the diocese, known locally as “the ambulance” because of the exterior resemblance, and from 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., he rescued young people who were fighting the government forces from a tranque (meaning an impromptu roadblock.)

“It wasn’t one, it wasn’t two… I rescued 19 young people with bullet wounds, including children,” he said. There was only one private clinic that would take the wounded, and for the least serious cases, they gave oxygen tanks and other medical aid kits that were put in the cathedral, so Brian would drive the wounded to church.

“During those days, the people in the pews didn’t listen to the Gospel, they lived the Gospel,” he said. Thousands came together to help, donate medical supplies, food, and do what they could for those wounded.

Today, the government is hunting them down. Policemen infiltrated the tranques and took pictures, and hundreds of those who’ve been identified are now in Chipote prison in Managua, or taken from their homes only to show up naked in the streets of the capital several days later.

Brian was also at the forefront when it came to freeing policemen held hostage by those in the tranques, but the government has insisted it was all theatre because they were “in on it.”

“I could hear the whistling of the bullets going around my head,” Brian said over a fruit salad he never finished. “Imagine what it was like for me, to see that my faithful were being killed.”

“We were accused of hiding weapons, but we never did,” he said. “The only weapon we had was Jesus in the Eucharist, and we would bring him out whenever there were protests, so people could pray.”

On Sept. 24, the feast day of the local patroness, Our Lady of La Merced, some 30,000 people took to local streets to celebrate the Church’s response.

“I saw Evangelical pastors who’d brought in their entire church to participate,” Brian said. “They saw that we were with the people, and now what is left for us to do is to remain with the people, that have been left poorer than before.”

The number of people who go to the local Caritas office to ask for food, he said, has tripled since April, and the situation is only bound to get worse. Yet despite the challenges, Brian said he’s not losing either his faith or his hope.

“We’re carrying a small piece of Jesus’ cross,” he said. “We wouldn’t be able to carry it in full, he’s helping us with that.”