Justice Antonin Scalia, a giant of American jurisprudence and a vocal defender of traditional Catholic morality, was fiercely protective of religion’s role in the public square, but he always insisted his faith did not impact his judicial rulings.

Scalia, who died Saturday at a ranch in West Texas where he was quail hunting, received the sacrament of the anointing of the sick, known colloquially as last rites, from a local priest, the Diocese of El Paso confirmed. The Rev. Mike Alcuino, who serves at a parish and several missions in the diocese, was called to the ranch where Scalia died at age 79.

Born in Trenton, NJ, in 1936, Scalia was a product of Jesuit education, graduating from Xavier High School in New York and Georgetown University in Washington, where he graduated first in his class, before earning his law degree at Harvard University.

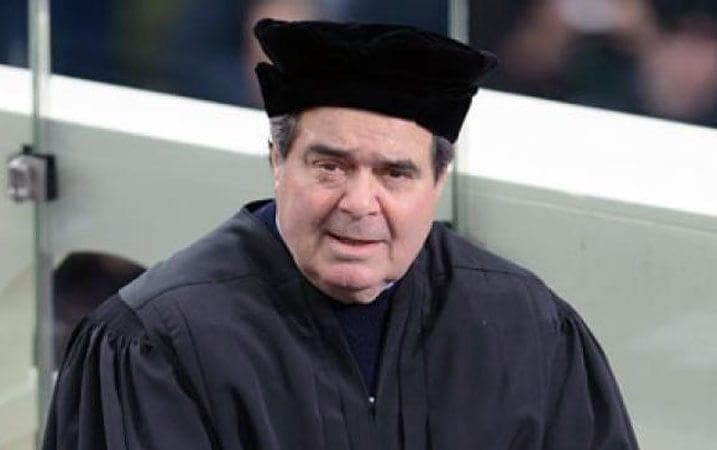

He was nominated to the US Supreme Court by President Ronald Reagan in 1986, and in his office he hung a portrait of St. Thomas More, the English Catholic martyr whom John Paul II dubbed the patron saint of statesmen and politicians. At President Barack Obama’s inauguration in 2013, Scalia wore a replica of a hat worn by More, revealed to be a gift from St. Thomas More Society of Richmond, Virginia.

In a 2013 interview with New York magazine, Scalia, a strong conservative who railed against abortion and same-sex marriage, was asked about Pope Francis, who had just days before the interview said that the Church needed to shift its focus away from those two issues.

“He’s the Vicar of Christ. He’s the chief. I don’t run down the pope,” Scalia said.

He said that if the pope’s popularity helped the Church evangelize, then he could get behind Francis.

“I have often bemoaned the fact that the Catholic Church has sort of lost that evangelistic spirit,” he said. “And if this pope brings it back, all the better.”

When Pope Francis spoke to Congress last September, Scalia did not attend. He and Justice Clarence Thomas have skipped most State of the Union speeches in recent years.

Although Scalia toed the Catholic line on abortion and traditional marriage, he publicly questioned the Church about its opposition to the death penalty.

Speaking at the University of Chicago Divinity School in 2002, Scalia said, “I do not find the death penalty immoral.” He said he took issue with Catholic thinkers who sought to use Pope John Paul II’s encyclical Evangelium Vitae as proof that the Church is against the death penalty.

“It would be remarkable to think otherwise — that a couple of paragraphs in an encyclical almost entirely devoted not to crime and punishment, but to abortion and euthanasia, was intended authoritatively to sweep aside (if one could) two thousand years of Christian teaching,” he said.

The Catholic Church teaches that the death penalty is acceptable only when no other means are available to protect populations from violence, but recent popes have suggested that this situation does not exist in today’s world. In fact, in his speech before Congress, Francis said the Church’s belief in the sanctity of life “has led me to advocate at different levels for the global abolition of the death penalty.”

But in the New York interview, Scalia spoke about his traditional Catholic beliefs, stating that he believes in heaven and hell (“Oh, of course I do.”) as well as the Devil.

“Of course! Yeah, he’s a real person. Hey, c’mon, that’s standard Catholic doctrine! Every Catholic believes that,” he said. “Most of mankind has believed in the Devil, for all of history. Many more intelligent people than you or me have believed in the Devil.”

Scalia attended Latin Masses, expressing disdain for the liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council.

“We have always traveled long distances to go to a church that we thought had a really reverent Mass, the kind of church that when you go in, it is quiet — not that kind of church where it is like a community hall and everybody is talking,” he said in “American Original,” a biography by veteran Washington journalist Joan Biskupic.

One of Scalia’s nine children, Paul, is a Catholic priest for the Diocese of Arlington, Virginia, and is active in the Latin Mass movement.

Scalia said on “60 Minutes” in 2008 that he and his wife, Maureen, “didn’t set out to have nine children,” alluding to the Church’s prohibition on contraception.

“We’re just old-fashioned Catholics, playing what used to be known as ‘Vatican Roulette,’” he said.

Scalia was one of five Catholic justices on the bench, a dramatic shift for a court that historically has had one “Catholic seat” since the appointment of Roger Taney in 1836, Elizabeth Dias noted in Time magazine.

“A big part of his legacy will be how navigated the relationship between one’s deeply held faith commitments and one’s role as a judge,” University of Notre Dame law professor Richard Garnett told Time. “For him, the way to navigate that relationship, it was not to compromise one’s religious faith or water it down, it was to distinguish between the legal questions the judge has the power to answer and the religious commitments that a judge has the right to hold, just like all of us do.”

Scalia’s death throws into even greater uncertainty several controversial cases slated to be argued before the Court this term, among them a suit brought by a group of Catholic nuns who are suing the Obama Administration over its religious exemption to the contraception mandate in the Affordable Care Act.

The Little Sisters of the Poor are set to argue next month that the compromise, in which they notify the government that they will not provide insurance coverage for contraception in order to kick in coverage from the insurer, infringes on their religious liberty.

If the case ends up tied, the lower court ruling stands, meaning the Little Sisters would lose their case.

Late Saturday, Obama called Scalia “a devout Catholic” and ordered the flag above the White House to be flown at half-staff. Despite Republican calls to let the next president appoint Scalia’s successor, Obama said he would nominate a replacement “in due time.”