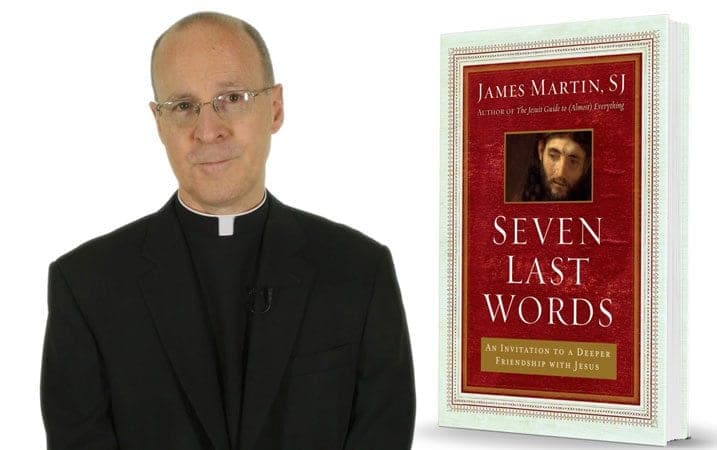

Excerpted from “Seven Last Words” by the Rev. James Martin, SJ, published February 2016 by HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Book Publishers, hardcover, RRP $18.99.

Chapter One: Jesus Understands the Challenge of Forgiveness

As they led him away, they seized a man, Simon of Cyrene, who was coming from the country, and they laid the cross on him, and made him carry it behind Jesus. A great number of the people followed him, and among them were women who were beating their breasts and wailing for him. But Jesus turned to them and said, “Daughters of Jerusalem, do not weep for me, but weep for yourselves and for your children. For the days are surely coming when they will say, ‘Blessed are the barren, and the wombs that never bore, and the breasts that never nursed.’ Then they will begin to say to the mountains, ‘Fall on us’; and to the hills, ‘Cover us.’ For if they do this when the wood is green, what will happen when it is dry?”

Two others also, who were criminals, were led away to be put to death with him. When they came to the place that is called The Skull, they crucified Jesus there with the criminals, one on his right and one on his left. Then Jesus said, “Father, forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing.” And they cast lots to divide his clothing. And the people stood by, watching; but the leaders scoffed at him, saying, “He saved others; let him save himself if he is the Messiah of God, his chosen one!” The soldiers also mocked him, coming up and offering him sour wine and saying, “If you are the King of the Jews, save yourself!”

— Luke 23:26–37

* * * * *

In our sometimes dark world we are often given moments of light that not only illumine our way, but remind us that God is with us.

One kind of these moments happens frequently, and you’ve probably heard about it, read about it, or even encountered it yourself. I’m speaking about moments of radical forgiveness: those amazing stories, which you’ve seen in newspapers, on television, or online, of men and women forgiving people responsible for horrific crimes committed against them or, more typically, against members of their families.

A Jesuit friend, for example, once told me a moving story about his family. One night, his father was awakened from a deep sleep and told that his sixteen-year-old son had been killed in a car accident while being driven by a friend named Kenny, who was drunk at the time. At the trial, the father pleaded with the judge to give Kenny the minimum sentence possible, because Kenny never wanted to kill his friend.

Afterward, my Jesuit friend asked his father how he could possibly do that. His father said, “I just did what I thought was right.” He also said that he saw Kenny as more than just that one terrible act. Today, my friend’s father still keeps in touch with Kenny, who now has his own children. For his part, Kenny has written faithfully for the last twenty years to the father of the boy whose death he caused.

And recently America magazine, where I work as an editor, published the remarkable story of a woman named Jeanne — an attorney, as it happens — who forgave the man who killed her sister, her sister’s husband, and their unborn child. The killer was remorseless and had never admitted his guilt.

Now here is a story of not an accidental death, but an intentional one, and — let me repeat — there was no remorse. I repeat that because many people believe you can’t forgive someone who isn’t sorry.

But Jeanne was able to forgive her sister’s murderer. She said that at the time the phrase “You take away the sins of the world,” which Catholics recite during the Mass, deeply moved her. Jeanne said she wasn’t sure if she’d ever fully understand what those words mean, but they surely don’t mean that we should take the sin a person commits and freeze it; that no matter what the person does, even if he or she repents, we should punish the person for it forever. It’s similar to what Sister Helen Prejean, CSJ, the author of “Dead Man Walking,” often says about inmates on death row: “People are more than the worst thing they’ve ever done in their lives.”

Years later, Jeanne realized that she had never told her sister’s murderer that she had forgiven him. So she wrote him a letter and did so.

In response, Jeanne received a letter of confession and remorse. He wrote, “You’re right, I am guilty of killing your sister . . . and her husband. . . . I also want to take this opportunity to express my deepest condolences and apologize to you.”

Forgiveness had freed him to be honest and remorseful.

I’m sure you’ve heard stories like this. I’m sure you’ve also seen occasions of the more common situation, where victims are given the opportunity in the courtroom to respond to the criminals, and they do not forgive. I’m sure you’ve seen videos of family members screaming at criminals: “I want you to suffer like I am!” “I hope you rot in jail!” “I hope you fry in the electric chair!” “I hope you go to hell!” It’s understandable. Anyone who is the victim of a crime or the relative or friend of a victim — particularly of a violent crime — should be forgiven for being angry. I would probably feel the same way. It’s human.

But the reason we respond so powerfully to those other situations, where radical forgiveness is offered, is that they’re divine. That’s why they touch us. Those moments speak to the deepest part of ourselves, which instinctively recognizes the divine. We see these moments as beautiful, because this is how God wants us to live. It’s a kind of call.

Now you may say, “Those are nice words, Father, but you don’t live in the real world. What do you know about that?”

Let me assure you, even in religious orders and in the priesthood one can find anger, bitterness, and ill will. But it’s easy to see where people get that idea. I’m sometimes susceptible to that kind of romanticism myself. Once I said to a Benedictine monk, “Well, I’m sure it’s easier in a monastery than it is in a Jesuit community.”

He just laughed and told me a funny story. One elderly monk in his community used to show his displeasure with other monks in a highly creative way. As you may know, most monastic communities chant the psalms several times a day together in chapel. Well, if this elderly monk was angry at someone, every time the word “enemy” came up in a psalm, as in “Deliver me from my enemies,” he would look up from his prayer book and glare at the monk he was angry with.

On a more personal note, I once lived in a community with a Jesuit who more or less refused to talk to me for ten years. He despised me and made that clear in almost every interaction we had — whether alone or in a group. At one point, I asked him if I had done anything to offend him, and he refused to answer. I never figured out what prompted his hatred, and he never changed his attitude. In desperation, I asked an elderly Jesuit priest, renowned for his holiness, for advice.

The only thing to do, he told me, is to forgive.

Now, you might be thinking of a situation in your own life and say, “I can never forgive. It’s impossible.” Then look at what Jesus does from the cross. If anyone had the right not to forgive, it was Jesus. If anyone had the right to lash out in anger, it was Jesus. If anyone had the right to feel unjustly persecuted, it was Jesus. Yet even though the Roman soldiers do not express remorse in front of him, Jesus not only forgives them; he prays for them. Notice that. Jesus says, “Father, forgive them.” He’s praying for them.

Now consider that line, “They do not know what they are doing.” That particular phrase helped me a great deal with the Jesuit who wouldn’t speak to me. He didn’t seem to know what he was doing. Indeed, people who sin sometimes don’t seem to be thinking clearly. This insight may help you on your road to forgiveness. It’s the same impulse that allows you to easily forgive a mentally ill person for doing something that seems thoughtless, rude, or even cruel.

Jesus does the same thing. Jesus always sees. And he sees beyond what people around him see. He sees people for who they really are. Forgiveness is a gift you give the other person and yourself. Jesus knows this. And he not only tells us this several times in the Gospels, but he shows us this. He is teaching us even from the cross.