It’s a commonplace of Catholic rhetoric to insist that “the Church is not a democracy,” and of course in many ways that’s true. Doctrines are not voted in and out by popular referendum, bishops are chosen by the pope rather than by plebiscite, and so on.

In democracies, power is understood to come from the bottom up, through the consent of the governed. In Catholicism, power comes from the top down, through the will of God.

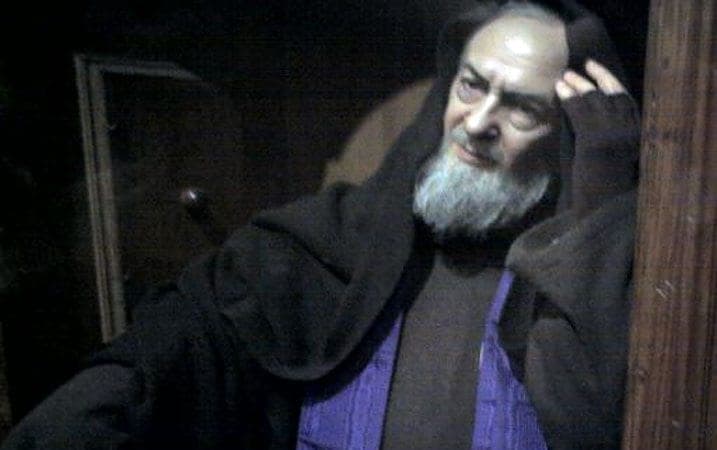

That’s not to say, however, that popular will has no impact at all in the Catholic Church, and perhaps nothing better illustrates the point than the story of Francesco Forgione, known for most of his life as Padre Pio, and now in death as Saint Pio of Pietrelcina.

The thought comes to mind as we near the feast day of Padre Pio on Sept. 23, the run-up to which at his shrine in San Giovanni Rotondo in Italy begins on Thursday with a novena of prayer. Because this year marks the 100th anniversary of his arrival at the Capuchin friary there, and because this is a jubilee Year of Mercy, for the first time the relics of the saint will be brought outside the church named for him and put on public view all night during the vigil before his feast.

It’s impossible to exaggerate the appeal of Padre Pio in Italy even now, almost fifty years after his death in 1968. Virtually every restaurant in the country, every bar, every cab, has a holy card or an image of the famed stigmatic and holy man.

Jokingly, I’ve often said that the Holy Trinity in Italy isn’t Father, Son and Holy Spirit; it’s God, the Virgin Mary and Padre Pio. In a declaration it intended to be ironic, the leftist newspaper Il Manifesto once dubbed him “the most important Italian of the 20th century,” but even in jest it’s probably an entirely accurate claim.

From a spiritual point of view, the appeal is obvious – Padre Pio is the patron saint of suffering humanity.

His own suffering is legendary, from the wounds of Christ he bore in his own body for 50 years beginning in 1918, to the impossibly long hours he spent in the confessional, even to the censure he received on multiple occasions from Church authorities.

As a result, people who suffer – and, let’s face it, at one point or another we all do – can see in Padre Pio a kindred spirit.

In terms of the dynamics of the Church, however, what’s most interesting about Padre Pio is that devotion to him came solidly from the ground up, often in defiance of the powers that be, and were it not for the unflagging will of the grassroots, he might never have been declared a saint.

The popular fascination started at the very beginning, when Padre Pio first reported his stigmata to his Capuchin superiors and word came down to impose “maximum reserve” about the phenomenon. Yet the rules of the day decreed that priests had to say Mass with their hands uncovered, so people could see the wounds, and with no help whatsoever from any official propaganda machine, Padre Pio quickly became a national and international phenomenon.

Over the years, many Church heavyweights sniffed at the devotion surrounding him. Padre Pio’s own archbishop for many years, Pasquale Gagliardi, was openly skeptical, writing the Vatican at one point to complain of lay sisters circulating in the streets of San Giovanni Rotondo with photos of Padre Pio around their necks, selling bloody handkerchiefs (which may or may not have been used by the Capuchin himself) to credulous pilgrims.

In 1922, Father Agostino Gemelli, a Franciscan and the founder of Rome’s famed Gemelli hospital, concluded that Padre Pio was a “hysteric” and his stigmata self-induced. There were rumors of Padre Pio ordering carbolic acid to produce his wounds, even of his having untoward relationships with some of his female devotees.

All told, he was investigated either by his own superiors or the Vatican somewhere between 12 and 25 times, depending on how you count, and at various stages he was barred from receiving visitors, hearing confessions, or saying Mass in public.

Through it all, the people stood by Padre Pio. How strong was their attachment? In 1930, when rumors spread that Padre Pio was to be sent away from San Giovanni Rotondo, an angry mob broke into the Capuchin friary to “rescue” him.

I vividly recall that in 2002, there were two great canonizations in Rome: St. Josemaría Escrivá, the founder of Opus Dei, and Padre Pio, and the crowds for the two big events couldn’t have been more different.

Escrivá drew a largely white collar following, composed of unfailingly polite, orderly men and women dressed in suits and dresses who followed the rules and picked up after themselves. Padre Pio, on the other hand, attracted a motley crew that at times bordered on a mob.

At one point, a colleague and I were making our way through the crowd to the press area and had to physically separate two rather large women who were brawling over a prized viewing spot. We managed to end the fistfight, but the shouting continued to echo in our ears as we walked away.

That, however, was always the secret to Padre Pio – elites, including in the Church, might view him with skepticism or disdain, but among ordinary folk he was a hero, and they’re the ones who ultimately propelled him to the halo. (They did so with an assist, of course, from St. Pope John Paul II, who met Padre Pio as a young priest in 1947, and who, as a fellow mystic, admired him.)

Padre Pio’s popular appeal was clear during his lifetime, and remains so today. In a recent poll, Italians were asked who they would be most likely to turn to in a time of need. By a landslide, the winner was Padre Pio.

Catholicism may not be a democracy, but Padre Pio clearly illustrates that the Church’s demos isn’t entirely powerless either.