ROME— Fidel Castro, Cuba’s communist leader who died on Friday at the age of 90, was by far the most dominant figure in Cuba’s one-party state which he ruled with an iron fist for almost five decades before handing over the powers to his brother Raúl in 2008.

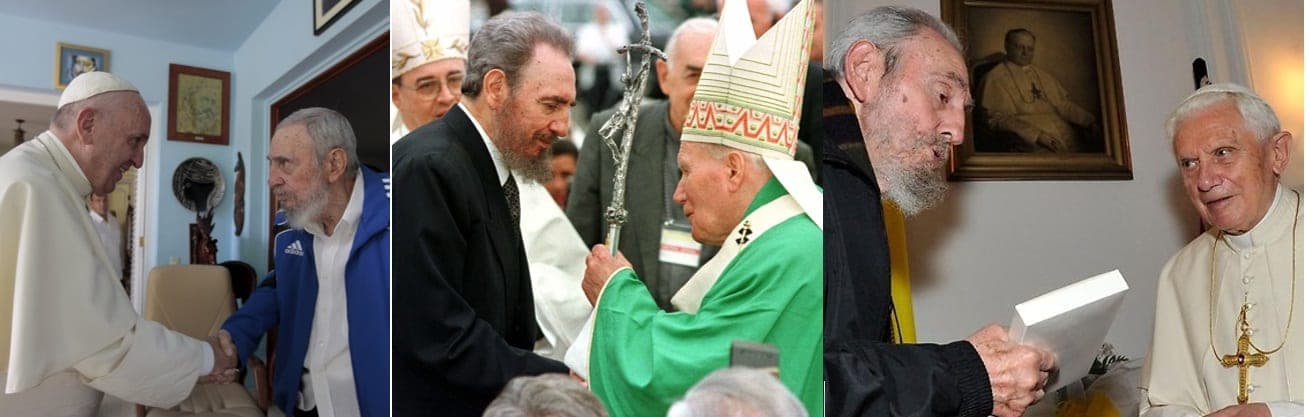

A hero to the left across the world, a hated figure to the right, especially in the United States, Castro is perhaps the only world leader to have received three popes — although when he met Benedict XVI in 2012 and Francis in 2015, he was technically no longer president.

However, in an unusual move, Crux understands that the Vatican is later today expected to issue a telegram of condolence, a gesture it normally reserves for heads of state who die in office.

Castro and Pope Francis

In his first speech upon arriving in Cuba, Francis asked Raúl Castro to “convey my sentiments of particular respect and consideration to your brother Fidel.”

Francis was the third pope to travel to the island nation after St. John Paul II in 1998 and Benedict XVI in 2012. Only Brazil and Mexico have received all three, but unlike Cuba, with a population of just 9m, they are the world’s largest Catholic countries.

Francis included a stop at Fidel’s residence, where the two had a private meeting. It was the seventh encounter between Castro and a pope: he’d had five with John Paul II, and one with Benedict XVI.

The meeting between Francis and Castro lasted 30 minutes, and at the time was described by the Vatican as “friendly and informal,” with the two swapping books about religion and talking about “the common problems of humanity,” including environmental degradation.

The pope gave Castro a copy of his encyclical on the environment, Laudato Si, a book by Italian priest Alessandro Pronzato and one by a Spanish Jesuit, Amando Llorente.

Llorente was the revolutionary leader’s teacher at the Jesuit-run Colegio de Belen (Bethlehem College) in the 1940s but was expelled by Castro in 1961 and died in Miami in 2010.

In a 2006 interview with the Miami Herald, the late Jesuit priest recalled how a teenage Fidel – whose father Angel was largely absent from his life – once confided in him: “I have no family other than you.”

Francis, in turn, received a book by Castro himself with his own insights on religion, a collection of interviews of the leader by Brazilian priest Frei Betto.

In 2014, both U.S. President Barack Obama and Raúl Castro thanked Francis for helping broker a deal to restore diplomatic relations between the two countries, something which wouldn’t have been possible without a nod from Fidel.

The Vatican’s role in Cuba-U.S. relations is almost as old as the conflict itself: Cuba is the only communist country with which the Holy See never broke off diplomatic relations, despite the repression of the Church in the first two decades after the 1959 revolution.

Francis wasn’t the first pope to write to both conflicting countries to ease the tensions. A year after the United States broke ties with its neighbor in 1961 Pope St. John XXIII wrote to both John F. Kennedy and Russia’s Nikita Khrushchev, much like Francis wrote to Obama and Castro, in an effort to avert a war.

Kennedy would later call the pope’s letter in the midst of the Cuban missile crisis “the first step down the path of peace.”

After Cuba was officially declared a Socialist state in 1961, the Catholic University of Villanueva was closed, 350 Catholic schools were nationalized, hundreds of churches were expropriated, and 136 priests were expelled. In 1969, the communist leader abolished paid Christmas holidays, claiming he needed everyone to work on the sugar harvest.

It wasn’t until 1976 that a new constitution guaranteed freedom of worship, but it was restricted to Church premises.

Castro and Pope St. John Paul II

Although it wasn’t the first time John Paul II and the late former leader met, that first papal visit to the island in 1998 was a pivotal moment and one which quite literally brought Christmas to Cuba, since as a welcoming gift the government announced the reinstatement of the holiday.

After John Paul II’s death in April 2005, Castro attended a mass in his honor in Havana’s cathedral and signed the Pope’s condolence book at the Vatican Embassy.

“Rest in peace, indefatigable battler for friendship among the peoples, enemy of war and friend of the poor,” Castro wrote in a long message.

“The efforts by those who wanted to use your prestige and your enormous spiritual authority against the just cause of our people in their struggle against the giant empire [the United States] were in vain,” he continued.

Fidel had visited John Paul II in the Vatican in 1996.

Castro and emeritus Pope Benedict XVI

Benedict XVI’s visit in 2012 had a similar impact to that of his predecessor: As a direct result, the government of Raúl Castro allowed Catholics to celebrate Good Friday. That year, the churches throughout the country were allowed to have outdoor processions for the first time in decades.

The pope met Castro in the home of the papal nuncio to Cuba at the request of the leader, who at the time had already left power. Father Federico Lombardi, then the papal spokesman, spoke of a “long and cordial” conversation.

They discussed a wide range of topics, such as Church liturgy and the state of the world, but also joked about their age – Castro was 86, Benedict is 84. At one point, Fidel Castro asked a simple question: “What does a pope do?”

“The pope told him of his ministry, his trips, and his service to the Church,” Lombardi said at the time.