With tough-talking President Rodrigo Duterte basking in a roughly 80 percent approval rating and his political rivals seemingly disorganized and reeling, there’s a strong case to be made that the Catholic Church in the Philippines, de facto, is quickly becoming the country’s strongest, if not really its only, opposition party.

Following a week in which Duterte’s violent war on drugs set a new record for lethality, with 81 alleged “drug suspects” killed in all, including a 17-year-old boy, the country’s bishops once again emerged as the president’s most outspoken moral critics.

Bishop Jose Oliveros of Malolos – located in the province of Bulacan about seven miles north of Manila, where 32 of the 81 deaths took place last week – directly called most of those fatalities cases of “extra-judicial killings,” despite the fact that Duterte and his supporters fiercely reject the use of that term.

“We are all concerned about the number of drug related killings in the province because they are mostly, if not all, extra-judicial killings,” Oliveros said.

Duterte on Wednesday exuded pride over the crackdown in Bulacan, saying, “That’s beautiful. If we can only kill 32 every day, then maybe we can reduce what ails this country.”

Oliveros suggested that the motive for at least some of those killings may simply have been an effort to give Duterte what he wants.

“We do not know the motivation of the police, why they had to do the killings in one day … maybe to impress the president, who wanted more,” he said.

Meanwhile, Bishop Pablo Virgilio David of Caloocan, a city which forms part of the larger Manila region, was even more pointed in his criticism, offering a comparison to the human rights abuses and authoritarianism under strongman Ferdinand Marcos in the 1970s and 80s.

“During Marcos’s time, ‘communist’ was used as a ‘label and justification’ for abductions and killings,” David said. “Now, it’s ‘drug suspects.’ I don’t know of any law in any civilized society that says a person deserves to die because he or she is a ‘drug suspect’.”

Caloocan was the home of a 17-year-old high school student named Kian Loyd Delos Santos, killed in Manila Thursday night as part of another anti-drug operation. Police initially claimed he was shot to death after opening fire on officers, but witnesses reported watching police force a gun into Santos’s hand, then compel him to run before shooting him down.

Three officers have been suspended over the incident pending an investigation.

David warned his fellow Filipinos, many of whom have applauded Duterte’s take-no-prisoners approach, that their turn could be next.

“You might be surprised to find your name in the list one of these days,” he said. “Anyone can be listed as a ‘drug suspect’.”

David was elected the new Vice President of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines at the group’s last meeting in July.

“A victim’s mother told me they know they are ‘unworthy’ people, and that no one would stand up for them,” David said. “It is as if we have accepted the narrative that people who use drugs deserve to die.”

To be sure, the drug was is not the only front on which Catholic bishops have issues with Duterte. Recently, for instance, one of his key allies floated a measure that would legalize both divorce (the Philippines is presently the only state in the world with no divorce law, other than the Vatican) and same-sex unions.

RELATED: Key ally of Philippines president introduces bills allowing for divorce, same-sex unions

Yet there’s no doubt the drug war is the most intense source of conflict. Since Duterte swept to power last summer, estimates are that almost 8,000 people have been killed in violence triggered by the war on drugs, mostly young males in slum neighborhoods. Some of those fatalities came at the hands of vigilante groups, which the government officially discourages but which claim to have Duterte’s tacit support.

In a series of reports last year, the Reuters news agency found that the police had a 97 percent kill rate in drug operations, which was considered the strongest proof to date that police were summarily shooting drug suspects.

In a pastoral letter last February, the bishops’ conference asserted that the government is creating a “reign of terror.”

RELATED: Duterte’s bloody war on drugs slammed as ‘ethnic cleansing’

“An even greater cause of concern is the indifference of many to this kind of wrong,” the bishops wrote. “It is considered as normal, and, even worse, something that (according to them) needs to be done.”

Duterte ran promising an aggressive crackdown on crime, and his focus on drugs in particular over the last year has been laser-like. According to a recent analysis by Philstar.com, a leading news site, Duterte has mentioned illegal drugs in 247 of the 304 public addresses he’s delivered as president.

While the strategy so far has galvanized strong popular support, it’s also brought international condemnations and scathing criticism from human rights groups. On the ground, however, the Catholic Church so far has been the lone institution with deep social influence to organize resistance.

Church organizations have trained pastoral workers in grief counseling, and raised funds to cover victims’ funerals and the survivors’ day-to-day living expenses. Some Catholic parishes even have become sanctuaries, offering refuge for people on village-level drug watch lists, which are often the basis for new police crackdowns, while other parishes have relocated entire families to distant provinces.

Many Catholic groups have also launched recovery and rehabilitation programs for drug users, touting treatment as the more humane alternative to violence.

Rise Up is a group formed by church officials and volunteers which provides counseling, burial services and interest-free loans to help families who have lost members. The church is also partnering with the Free Legal Assistance Group, the largest body of human rights lawyers in the country, to train pastoral workers to collect eye-witness accounts of alleged police brutality and excessive force, along with copies of official police and autopsy reports.

Although comparisons are inevitable with the “People Power” movement in the 1980s, when the Catholic Church led a national uprising that swept Marcos from power, observers say the situation in the Philippines today is markedly different.

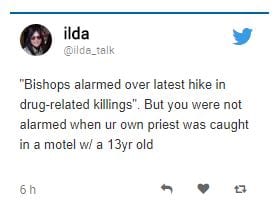

For one thing, the Church’s own moral authority has been frayed by a series of corruption and abuse scandals. In late July, for instance, a Catholic parish priest was arrested in a city that makes up the greater Manila area while en route to a motel with a 13-year-old girl, after allegedly using text messages to arrange a sexual encounter with her.

RELATED: Diocese in Philippines will ‘fully cooperate’ after priest arrested for child prostitution

After several bishops denounced last week’s death count in the war on drugs, blowback on social media platforms in the Philippines highlighted such scandals.

Such open derision of Church leaders would have been almost unthinkable during the People Power era, under the legendary late Cardinal Jaime Sin of Manila.

Moreover, Catholic observers say that while bishops may be reasonably compact in their stance, that’s not true of all clergy, and definitely not of Catholic laity. The Philippines is 90 percent Catholic, so obviously much of Duterte’s support is coming from Catholics.

Father Joselito “Bong” Sarabia, a parish priest and counselor, recently said that some of his fellow priests voted for and still support Duterte, while others have chosen to remain silent out of fear of possible retaliation from vigilantes or vicious online attacks from Duterte supporters.

Despite all that, signs point to an escalating struggle between Duterte’s forces and the bishops over the country’s future.

“We cannot let these killings continue,” said David recently, the new vice president of the bishops’ conference. “We will lose our conscience and our soul.”

For his part, Duerte has brusquely dismissed criticism from the bishops on several occasions, and shows no signs of backing down.

In his second State of the Nation Address in July, he said, “I have resolved that no matter how long it takes, the fight against illegal drugs will continue. … The fight will be unremitting as it will be unrelenting. Despite international and local pressures, the fight will not stop.”

“The alternatives,” he said, in an ominous warning to anyone on one of his suspect lists, “are either jail or hell.”