YAOUNDÉ, Cameroon – Christians in Mali have come under systematic attacks by extremist Muslims, and the Catholic bishops say they are “deeply worried” about the lack of a government response to the crisis.

Mali is 90 percent Muslim, and Christians make up just 2 percent of the population. It is estimated there are 200,000 Catholics in the country, and around 100,000 people belonging to other Christian communities.

Jihadists who used to operate mostly in the north of the country are now launching incursions on the center of the country.

Monsignor Edmond Dembélé, the secretary general of the bishops’ conference, told Jeune Afrique Christian places of worship are a frequent target of attack.

He recalled a recent attack in the village of Dobara, about 500 miles north of the capital Bamako, where armed men stormed the local church, taking the crucifix, altar furnishings, and the statue of the Virgin Mary. They burned the church material right at the church door.

In September in the locality of Bodwal, Christians were chased away from their church with the threat that if they kept worshiping, they would be killed.

Over the next few weeks, several churches were burned in Mali’s central Mopti region, forcing parishioners to flee.

Dembélé lamented the fact the government was not providing more adequate security, making it hard for Christians to continue worshiping in what the government insists is a “lay state in which all religions have a right to co-exist.”

“We have no security program of our own and we rely on the authorities to provide protection and find solutions,” Dembélé said. “On previous occasions, the government has deployed military units in our parishes. But this still hasn’t been done against these new attacks.”

Human Rights Watch published a disturbing report in September that documented “serious abuses by Islamist armed groups in central Mali … including summary executions of civilians and Malian army soldiers, destruction of schools, and recruitment and use of children as soldiers. Increasing intercommunal violence near Koro, in Mopti region, has raised concerns of more widespread abuses.”

But the report also accused the Malian army of similar crimes, noting that “Malian forces have committed extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, torture, and arbitrary arrests against men accused of supporting Islamist armed groups.”

The rights group says such actions by the authorities further escalate the violence.

“The skewed logic of torturing, killing, and ‘disappearing’ people in the name of security only fuels Mali’s growing cycle of violence and abuse,” said Corinne Dufka, Sahel director at Human Rights Watch.

Understanding the Attacks on Churches

To understand what is happening to the Catholic Church in Mali, it is essential to understand the history of the current insecurity in the country.

In January 2012, members of Mali’s Tuareg ethnic group, who had been fighting to defend the regime of Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi returned home after the fall of his regime. When they returned, they still had heavy weapons from the Libyan conflict.

With this armory, they became the fighting arm of the Azawad National Liberation Movement (known by the French acronym MNLA), and quickly overran most of the north of Mali, taking over the three largest cities of Kidal, Gao, and Timbuktu.

They then declared the north an independent state named Azawad, an act that received no international recognition, and was opposed by several Islamist groups active in the region, Ansar Dine, Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa, and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb.

These groups chased the MNLA out of the major cities, and proclaimed that their strict version of Sharia – the Islamic law system – was in effect. This meant things such as alcohol, cigarettes, and western music were banned.

Christians were particularly targeted in these areas, and many of them fled the country to Niger and Burkina Faso.

In 2013, French troops were sent into Mali to oust the Islamists, and supported by both the Malian army and the MNLA.

In 2015, a peace deal was signed, allowing for the integration of rebel fighters into the regular army, but it soon collapsed.

Into this vacuum a myriad of armed forces continue to operate: The army, the MNLA and other Tuareg groups, and Islamists.

One of the major incidents was an August 2015 Islamist attack on a hotel in Sévaré, located in the central Mopti region, in which 13 people were killed.

“There are so many armed groups now, all trying to prove themselves,” Dembélé said.

He worries that even when the crisis comes to an end, Christians returning home will face destroyed houses and damaged property.

“There will be a lot of rebuilding to be done,” he said.

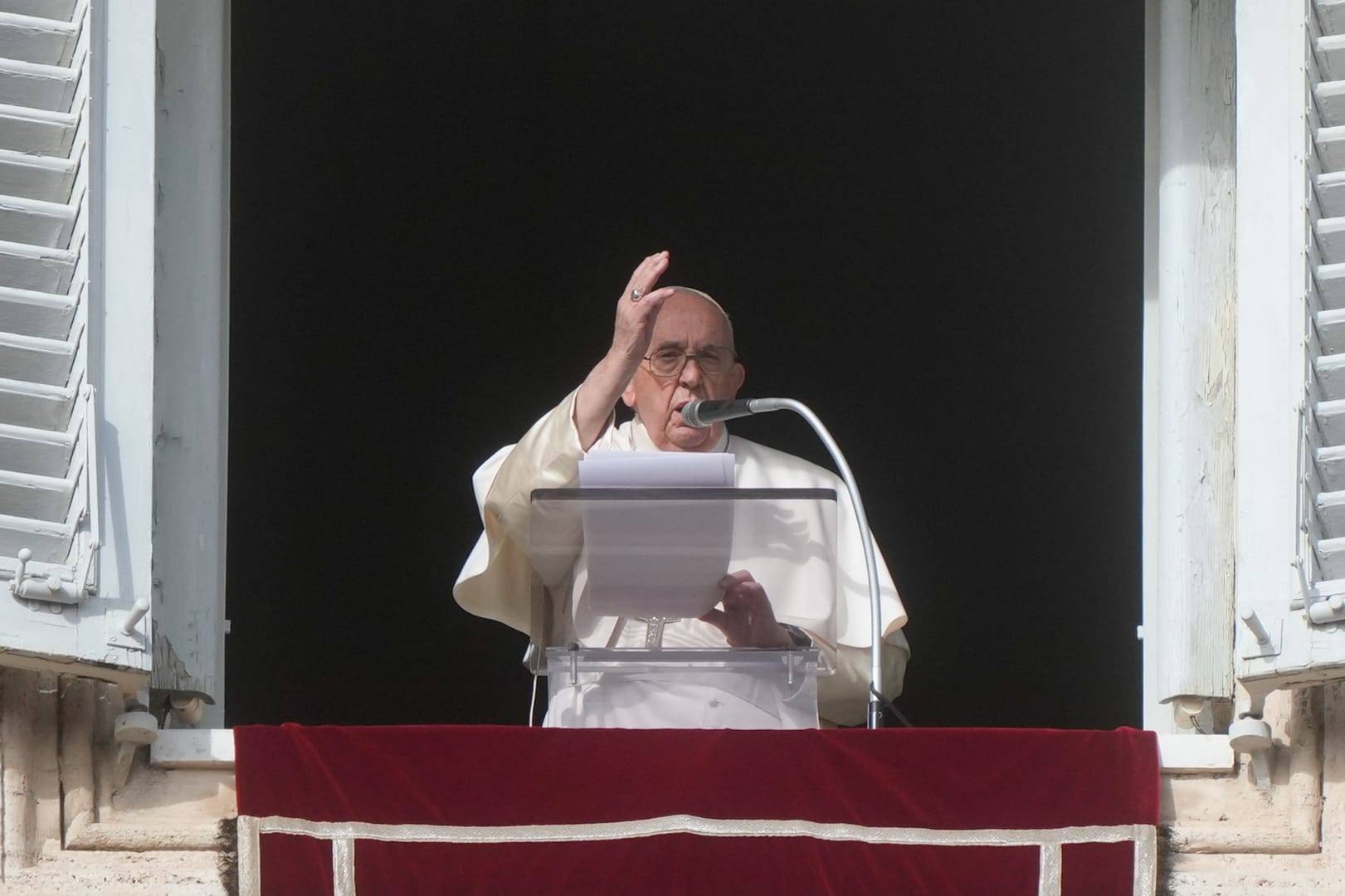

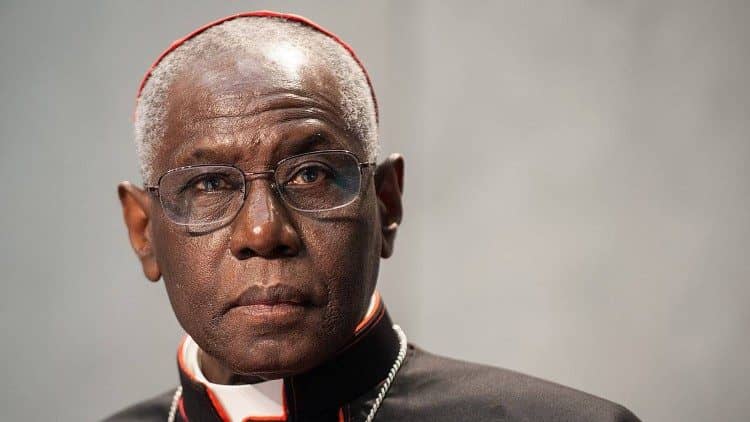

Pope Francis showed his solidarity with the people of Mali when he made Archbishop Jean Zerbo a cardinal on June 28, 2017. The archbishop of the Malian capital Bamako, Zerbo is the first cardinal from the country.

The pope said the appointment was an effort to highlight “those neglected areas and complex situations of war and poverty, while it reaffirms the interest of the Catholic Church.”