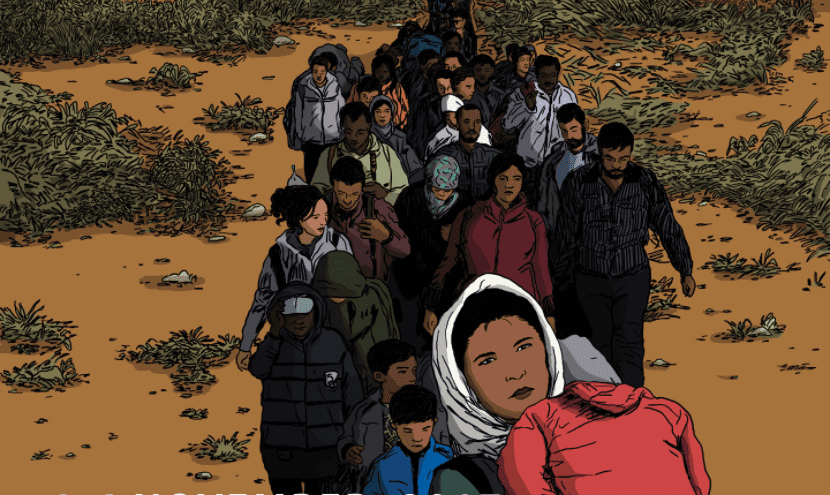

ROME – There are currently over 65 million refugees and internally displaced people in the world, half of whom are minors. That’s roughly the population of the United Kingdom.

Such a massive number of people living at the margins of countries and society, without a means of participating actively to further their own development and that of the hosting nations, is not only a human tragedy but also – according to participants at a conference in Rome this week – a waste of untapped human potential.

Activists, academics, and religious from all over the globe have been meeting in Rome Nov. 1–4 to discuss the role of universities and educators in offering help to the ever-growing numbers of migrants and displaced persons in the world.

The conference, ‘Refugees and Migrants in a Globalized World: Responsibility and Responses of Universities,’ is hosted by the Gregorian University in Rome and organized by the International Federation of Catholic Universities (IFCU), the Being the Blessing Foundation and the Center for Interreligious Understanding, along with a dozen Catholic higher education institutions.

“In the summer of 2016, the idea came to me that given the reality of the refugee crisis we ought to bring together university leaders to discuss the responsibility and response of the universities, refugees and migrants in a globalized world,” said Anthony Cernera, President of Being the Blessing Foundation, during a press conference at the Vatican Oct. 31.

Organizers echoed the call of Pope Francis to promote a more integrated response to the immigration crisis, one that includes not only universities, but also NGOs and non-profit organizations.

“No university can respond alone to something like this: In my opinion, we are dealing here with a truly international issue nowadays, and no single university can offer a response befitting the current demand,” said Father Pedro Rubens, President of the IFCU.

“When migration is interpreted as a sign of our times – and this surely echoes a theological form of thinking that is distinctive of Catholic universities – we can see in it a divine project, one of making the world one, of making it whole, and that encompasses the contribution of migrants and refugees, as well,” said Father Fabio Baggio, the Under-Secretary of the Migrants and Refugees Section at the Vatican’s new office for Integral Human Development.

What Western Nations can learn from Africa

“In Africa there is a slightly different narrative around migration,” said Father David Holdcroft, the regional director of the Jesuit Refugee Service in Southern Africa.

“Let’s face it: Africans are more experienced at it by around a hundred thousand years,” he told Crux.

A native of Australia, Holdcroft has over a decade of experience working with immigrants and refugees in Africa.

He said countries such as Uganda and Tanzania are starting to alter their stance on refugees due to their experience, and are beginning to see the potential that they can offer.

“These countries are very poor, they haven’t developed well over many years in the postcolonial phase, and here’s something that seems like a liability that is actually an opportunity,” the priest said.

Holdcroft pointed to the statistics presented at the conference showing the large number of displaced people in the world who “are in a situation where they are prevented from contributing positively to a community, to the progress of humanity,” calling it “an absolute disaster by any criteria.”

He said that once the situation of crisis is mitigated and their basic needs are met, immigrants and refugees don’t want handouts: They want an education.

Programs such as those conducted by JRS to provide on-the-ground management for universities to offer courses for displaced people can provide them with a useful set of skills, and help them use the refugee experience to inform their work and thinking.

“Our concern is for the end product, what happens actually after the course,” Holdcroft said. “We know that 98 out of 100 refugees will actually stay in their host countries or perhaps return to their original country, so how can we build an environment where they are serving with their own contribution to their own countries?”

Professionally-oriented courses in teaching, nursing, IT, translation, hospitality and management have proved to be the most effective in helping migrants and refugees hone their skills and generate income, which in turn opens the door for further education, the Jesuit said.

There are many challenges to providing education for immigrants. Many abandon their coursework because they become discouraged or intimidated by the cultural, economic, and didactic differences.

“If there is a sense of very deep poverty from which there is no escape, then these people – we have very good research on this right now – are more susceptible to participate in violent ideology,” Holdcroft said.

Promoting and creating collaboration between the universities and the NGOs is another challenge, he added, which can sometimes bog down programs.

But in spite of the obstacles, Holdcroft is optimistic.

In order to attract capital, refugees who take part in the courses are encouraged to work together after graduating.

“Often the people who band together are from across groups that have previously been in conflict where they are from,” he said, calling it an opportunity for peacebuilding.

African countries such as Chad, Northern Kenya, Sudan, Central African Republic are in the bottom percentiles of global development rankings, while at the same time are hosting a huge number of refugees.

“They are beginning to see that refugees are part of the solution and not, traditionally thinking, a part of the problem,” Holdcroft said.

He mentioned the immigration minister in South Africa, who recently said that refugees bring an entrepreneurial drive that is lacking in the country, calling the populace to “join these dots.”

“That’s a really hopeful message,” Holdcroft said. “And for me, Western nations need to learn from this.”

Educating governments, citizens and the media

Data in Europe shows that the number of immigrants has been decreasing since its spike in 2015.

Then why is migration still dominating the front pages?

That’s what Monica Attias wants to know. She works with the Community of Sant’Egidio, a Rome-based Catholic organization active in caring for immigrants and refugees.

According to Attias the problem is created by a clash between the need for security and the need for humanitarian action.

She says the Catholic Church, under the leadership of Pope Francis, is pushing for the latter, leading the way toward a more inclusive and welcoming society for immigrants.

“It’s first and foremost a Christian response to the deaths in the Mediterranean, but also to the human trafficking,” Attias said.

Sant’Egidio pioneered ‘human corridor’ initiatives in Italy, which provides safe and legal ways for immigrants to flee countries at war, such as Ethiopia and Syria, and come to Europe.

This model is currently being explored by many other countries.

To help with integration, Sant’Egidio has encouraged Italian families to host and welcome refugees into their homes.

Attias said that the testimonies show that they have now become positive members of the community.

“The narrative in Europe is exactly the opposite: That immigrants and refugees are destabilizing the countries,” she said. “The public opinion neglects that the presence of migrants is a positive influence on the nation.”

In Italy more than 2 million immigrants have steady jobs, constituting 10 percent of the workforce, and contributing up to 9 percent of the GDP.

“The response of a number of countries to immigration is to build walls, to send people back to where they came from,” said Michel Roy, Secretary General of Caritas Internationalis. “We have to promote the fact that migrants are bringing wealth to the countries that welcome them.”

Roy pointed to the ‘Share the Journey’ initiative launched by Pope Francis and Caritas, which invites people to have an encounter with immigrants and refugees in order to take away some of the prejudices and stigmas surrounding migration.

The Vatican also presented a series of 20 points, including one on education, to the United Nations to be integrated into the global agreements on the immigration crisis.

Attias told Crux that when managing the media, the Church must act like “doves but also like snakes,” by bringing to its attention the stories that are positive and important.

“It must be one of the dimensions of the job, to be very carefully present in the media, to signal situations that deserve attention because this is the way people achieve their education,” she said.

But the responsibility does not only lie in the hands of the media: People also have a fundamental role in selecting where they get their information.

“You choose the news you want to read and the channel you want to [hear],” Roy said.