ROME – For seventy years, the Vatican and China have had no formal diplomatic relations, Catholicism remains under pressure in the country, and a share of the twelve million Catholics living there profess their faith clandestinely. Recently, credible rumors of a deal with China have been resurfacing.

According to Vatican officials, the accord would hand the Chinese government a considerable degree of control over the nomination of bishops, a thorny issue in the relationship between the two states. It would seem that the upcoming deal would allow the Chinese government to choose the bishops, which the pope would then have a chance to veto.

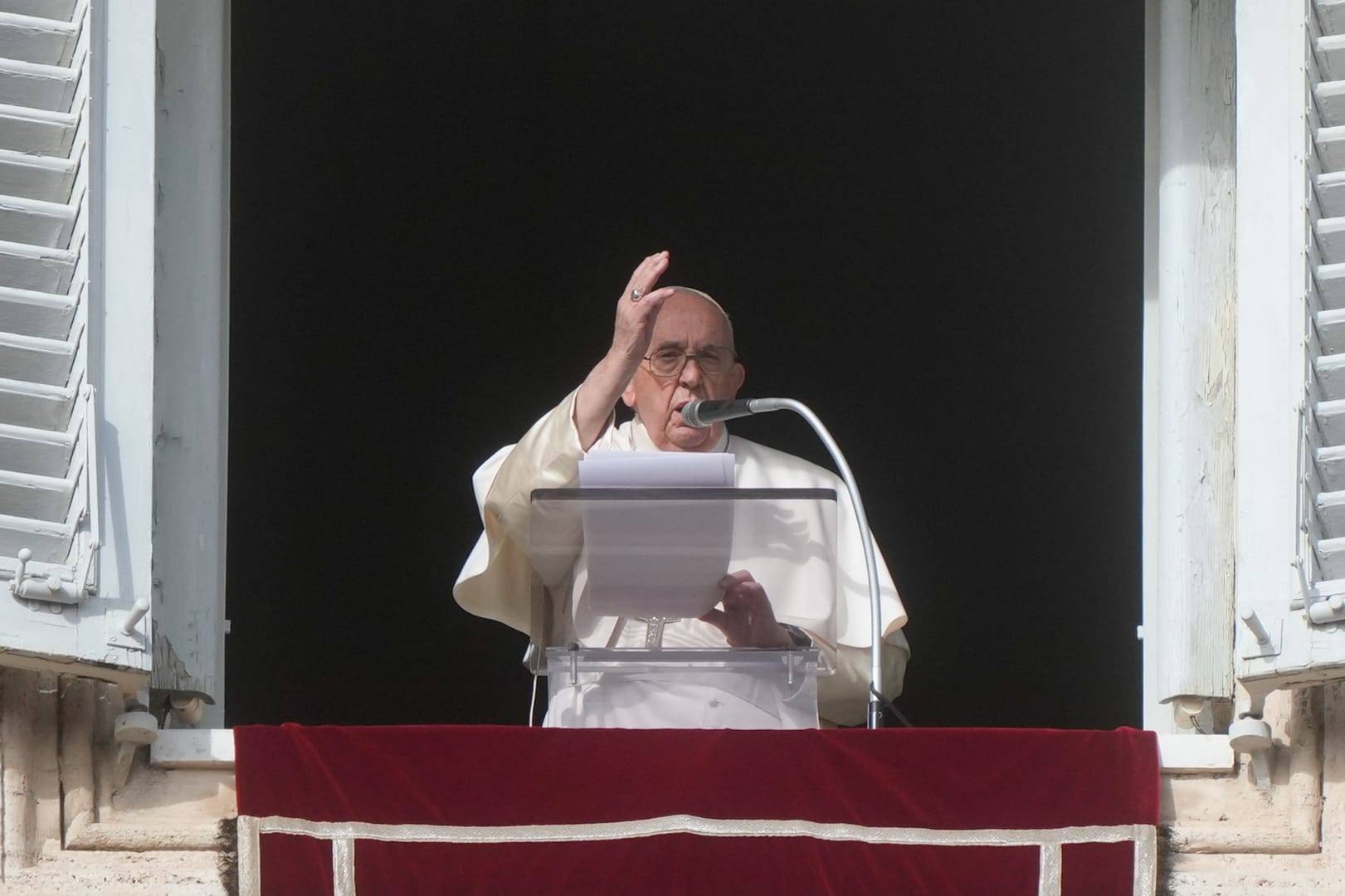

“The Holy See works to find a synthesis of truth, and a practical way to answer the legitimate expectations of the faithful, inside and outside of China,” said the Vatican’s Secretary of State, Italian Cardinal Pietro Parolin, in an interview with the Italian news outlet La Stampa.

“We need more caution and moderation on behalf of everyone in order to not fall into sterile criticisms that hurt communion and rob us of the hope of a better future,” he added.

Though the deal with China would not be the first time that the Vatican has compromised its power over the appointment of bishops to obtain a greater goal, the move has been criticized by those who view it as “selling out” the Chinese Catholics to the government, such as the former Bishop of Hong Kong, Cardinal Joseph Zen.

According to Father Bernardo Cervellera, director of the agency Asia News of the Pontifical Institute for Foreign Missions, the deal with China would be damaging in a unique way compared to previous agreements with other countries.

Unlike Vietnam, where the pope makes an initial selection that is then reviewed by the government, the deal with China would be the other way around, resulting in a “special case” which, according to Cervellera, has no justification.

“This makes the Sino-Vatican deal ‘limp,’” according to the priest and journalist, and opens the door to the possibility for the Chinese government to select “malleable, controllable” bishops who will in turn work in the interest of the state and not of the Church.

“When there are ever more bishops chosen by the government, and when they execute the policies of the government […], because they’re under control, to create an independent church, it effectively becomes a problem that’s almost schismatic,” Cervellera said.

“It becomes a national church of the state.”

Despite internal ecclesiastical divisions, it’s actually the unity of the Catholic Church that frightens Beijing most, he added, stating that more than any other religious community, Catholics are the ones looked at with concern.

Following is a transcript of the Crux interview with Cervellera.

Crux: Looking at the deal with China from the outside, some might ask: What’s the problem? It seems logical that the Vatican might want to have a diplomatic relationship with China, and all of us know that through the centuries there have been several deals regarding the appointment of bishops. The idea of a civil authority having a say in the matter is no novelty.

Why not make this deal?

Father Bernardo Cervellera: I think that there is, first of all, a problem of communication regarding the Vatican. Instead of saying ‘we are making a deal,’ snippets come out saying that all bishops will be recognized. Naturally this creates difficulties for the Chinese Church because everyone wants to know whether all the bishops, including the illicit (Chinese government appointed) ones, are included in the deal and if those not recognized by the government are included, meaning all the underground bishops. Because otherwise the deal risks being ‘limp.’ This is the main concern.

There is also an issue when saying: ‘The Vatican accepts illicit bishops.’ This is wrong. The Vatican will reconcile with the illicit bishops, which is a religious thing that has to do with the faith of the Christian community and has nothing to do with the government.

The problem is, what weight do the government and the Vatican have in this deal? From the vague information that is going around, China – as stated by the director of Religious Affairs – simply wants to continue its policy of nominating bishops and the pope would just have the function of blessing what they decide.

Many Catholics who see in the government influence a negative element for the life of the Church, believe that this would mean handing in the Church to the Chinese government. These are understandable and sharable concerns. Cardinal Pietro Paolo Parolin (the Vatican’s Secretary of State) has released an interview on his favorite news outlet, Vatican Insider, where he stated that the deal is being made for reasons of faith because we wish to help the Church be united, because we fear that things might get worse in the future and thirdly, because though we know that this is a bad deal, better a bad deal than no deal at all.

To each his opinion. Cardinal Joseph Zen (Former bishop of Hong Kong), who sees firsthand all the problems that the underground Church has, says better to have a deal where we ask China for more.

Some say that through the centuries the Church has made deals with many governments and even with Franco’s dictatorship in Spain. But Franco’s dictatorship was 80 years ago. We can’t understand why China must be a special case compared to what all the other states do.

China, so modern from a technological, economic, scientific and astronomic research perspective, is this way considered as a relic of the most retrograde Chinese empire. Or a relic of the most ancient feudal fights, because this is practically a fight for investitures, which took place more than a thousand years ago.

Just a few months ago I knew that the deal was that the pope only had a temporal veto for three months on a bishop. Then, it was said, that if the bishop’s council did not believe that the objections of the pope were appropriate it could continue as if nothing happened.

It’s risky because it puts in the hands of the government the possibility to choose all the bishops it wanted depending on the criteria it has always had, that is choosing the most malleable, controllable ones and make them into an instrument of their politics instead of them working for the evangelization of China.

When evaluating risks, is the underground Church better off now, without a deal, or in a situation where at least there is a “limp” deal?

This is an issue that is tied to the function of the (government controlled) Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association. Pope Benedict XVI’s letter to the Chinese Catholics in 2007, which Pope Francis has stated to be the basis of all his dialogues with China, said that bishops must try and communicate with the government and, if it’s not possible to do otherwise, participate in these organizations, while keeping in mind that these associations are incompatible with Catholic doctrine. This has to be done with the priests and the faithful and even if one becomes a part of the Patriotic Association, it must be done while keeping in mind the interests of the Church.

This happens for many bishops of the official Church, though some according to the faithful don’t do this, because they are taken by the government and don’t have a life at all: they are taken away from the diocese for many months and they repeat that their ideal is an independent Church (meaning independent from the Vatican, from foreign interests, the pope). In secret they say that they follow the Catholic faith, but in public they do what the government wants.

How can faithful trust these bishops? Even if they become official, how can they trust these ambiguous bishops? Benedict XVI once called them “opportunistic,” and there are many. Even among the seven illicit ones, there are a few opportunistic ones.

The other question is that the faithful in the underground Church are currently freer without the constant control of the Patriotic Association. One only has to see what is happening in the official Church, which is controlled completely. There are cameras in the parish offices, in the corridors, the police are always there. This is because China greatly fears religions.

Does it fear the Catholic Church more than any other religion?

Yes, it fears the Catholic Church more. A member of the Communist Party once told me this: ‘We fear the Catholic Church because you are united,’ he said. ‘If something happens to a Catholic, immediately all the other Catholics in the world talk, say, act! We are very afraid of your unity.’

The question remains the underground bishops, because for what we know and what was officially said by Chinese Cardinal Tong Hon last year, the underground bishops are the biggest problem in the dialogue between China and the Vatican and the Chinese government does not want to recognize them at all, because they don’t trust them. These people who have been martyred, who have been imprisoned, who have tried to follow the indications by the Vatican and not belong to the Patriotic Association in order to be free for the faith are now set aside.

In the interview, Parolin mentioned that it would be a sacrifice made for the Catholic Community as a whole. What is your opinion?

It’s a big sacrifice. You say, let’s make a deal, but a deal in order to obtain what? We lose half the Church, we put the nomination of the bishops in the hands of the government…Around two years ago a Chinese official interviewed by the Global Times refused a Vietnam style of investitures, where the Vatican proposes the candidates and the government chooses one among them, to be then approved by the pope. In this case the Chinese government chooses the bishops and the pope has to make the blessing. There is a bigger influence of the government. We put the bishops in the hands of the government, we don’t give the underground bishops a chance to be recognized… it seems like a complete loss. Why make a deal like that?

Then why make the deal?

I think that on one hand the Vatican is afraid that the Chinese Ministry of Religious affairs, as it has always promised, will appoint many bishops without papal approval, at least twenty dioceses. Twenty dioceses are at least one fifth of all the dioceses in China. I imagine that the Vatican is worried that if the number of basically excommunicated bishops grows so much, it might become even harder to build something.

The second thing that they say is that in the future things will probably get worse. So it’s better to take this deal, even if it’s bad, as a lesser evil. Could the future be worse? Effectively yes, but this future has already begun.

With the new regulations, in practice everything is being controlled, the bureaucracy has been augmented. To do anything – for instance, to repair a church, to hold a meeting, to bring in a professor or organize lessons, whatever – you have to ask permission from the municipality, the county, the province, and the federal government. They all have expiration dates of three months, so if you want to hold a meeting, you have to start a year and a half in advance!

How do you see this possibility of a schism?

The idea of a schism because this accord is signed, and some don’t accept it, seems to me to have very low probability. The underground bishops who would be set aside have already said that if the pope asks us for our obedience, we’ll obey and good night. Indeed, Giuseppe Wei Jingyi gave a terrific interview in which he said that instead of a breaking point in division, we want the faithful to follow the pope, etc.

The problem was exactly this: The pope’s search for spaces to meet the Chinese people seemed like a secret political dialogue, and not a pastoral path.

The real problem regarding a schism is what Zen says, and I agree with him. When there are ever more bishops chosen by the government, and when they execute the policies of the government … let’s say, they’re compelled to say and do [what the government wants], because they’re under control, to create an independent church, that effectively becomes a problem that’s almost schismatic. It becomes a national church of the state.

Sure, you can hope that the Catholics will carry on, secretly trying to follow the indications of the pope, but it will all be really difficult. I see now, when I go to China and meet an official bishop, they don’t want to talk, because they say people from the Patriotic Association are there, we can’t talk, we can’t talk. I go to talk to a bishop in Peking, and he says, no, we can’t talk, because the place is bugged. We’re practically in a concentration camp left open. These poor people, I’m not sure they can live.

The real problem is the bishops of the official church … there won’t be a schism of the subterranean church saying, ‘No, we don’t agree with this decision.’ This has already been said, and the priests, in conscience, will decide what to do, if they can participate and collaborate with the government or not. Many will say, if it’s something that doesn’t contradict my faith, okay, but if it does, I won’t do it. That’s not a schism, because all of them will remain connected to the pope. It will be a problem if the government continues to interfere in the life of the church, naming bishops, it will create a national church ever more …

Gallican?

Yes, Gallican.

[The term refers to a 17th century idea that originated in France that the civil power should have as much, or more, authority over the Church as the pope. It’s become a catch-all term for a national church, one loyal to a national government rather than Rome.]