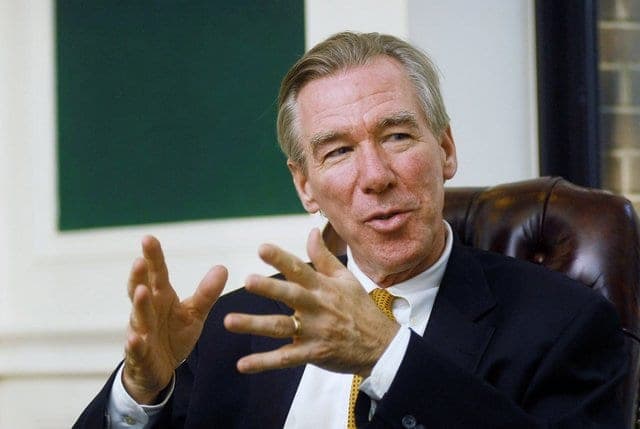

[Editor’s Note: John Garvey became the 15th president of The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., on July 1, 2010. Garvey is a nationally recognized expert in constitutional law, religious liberty, and the First Amendment. He recently expressed concern over the nature of the questioning of some senators during the confirmation hearings of a Catholic judicial nominee, with whom he had co-written an article. Charles Camosy spoke to him about the role of religion in public life, and what the place of the university is in a world where the civil discussion of ideas is becoming harder to do. The interview has been edited for length.]

Camosy: The U.S. seems to be in the midst of cultural storm surrounding the place of religious claims in public life. Do you share that sense?

Garvey: I do. It’s been happening for some time. There is an increasing tendency to relegate religious activity to places of worship, and to characterize it as a private matter, not permitted in public life (Hobby Lobby, Little Sisters, Masterpiece Cakeshop, Abeles, etc.) We see this most often on the left, but it also happens on the right (in our treatment of Muslims, for example).

This is not what the founders intended when they adopted the 1st amendment. The Constitution’s aim is to keep the government out of religious practice. It’s not to confine the behavior of private individuals and institutions to some small unseen place.

Think of the role religion has played in the public life of this country – from the abolition movement of the 19th century to the civil rights movement of the 20th. Martin Luther King preached the Gospel to his fellow citizens.

Let me add that secularism has its own dogmas and doctrines. And, increasingly, people are not only asked to tolerate them but to celebrate and participate in them.

The other side of this cultural coin, of course, is how the broader culture engages Catholic institutions, ideas, and practices. We saw this issue raised quite directly when Senator Feinstein and others questioned your former student, and current Notre Dame professor, Amy Barrett during her confirmation hearing for the Federal Appeals Court. You were outspoken in your support of her, and rightly challenged the suspicion with which people of firm religious commitment are held in an ever-increasing number of circles. Now that you’ve had a couple weeks to reflect on what went down in those hearings, do you have further thoughts on what this attitude toward religious belief portends for the future?

What I found most unfortunate about the Barrett hearings (or more precisely, the position Senators [Dianne] Feinstein, [Dick] Durbin, and [Mazi] Hirono took) was the implication that a certain kind of Catholic should not be allowed to serve as a federal judge. That is something the Religious Test Clause was meant to prevent.

Prof. Barrett (and I; we wrote this article together) recognized that there would be occasions when a federal judge might face a conflict between her religious convictions and her oath as a judge. But we both said then, and she repeated in her hearing, that the proper resolution to that sort of conflict was recusal – a course of action provided by statute for just such a predicament.

As a result of this storm, secular universities are faced with increased public pressure to refuse platforms to those who hold traditionally religious views, especially on matters of sexuality and reproduction. Many Catholic universities face a similar kind of pressure from many academic quarters, but at the same time face pressure to honor the very religious views that so many in the broader academy find so problematic. In your experience, what are some best practices for negotiating this daunting set of pressures?

Universities should be places where there can be civil exchanges of ideas, debates, and discussions. We do ourselves a disservice if we consent only to engage with people in an echo chamber, who align with our every position or commitment.

Here is one best practice I recommend to schools. In first amendment law we draw a distinction between private speech and government speech. The government can’t regulate private speech – what I say on a street corner, what the New York Times publishes in the weekend edition. On the other hand, the government has complete control over what it wants to say: The President can oppose immigration or support affirmative action.

We might apply a similar principle at universities. It is one thing to have our students invite a speaker. That is like private speech. It’s another matter for the University itself to choose a commencement speaker, or the person who gives an endowed lecture. That is “university speech,” just as setting the curriculum or hiring faculty is university speech.

You recently had a test case when CUA’s Theological College disinvited Jesuit Father James Martin from giving a talk on Jesus. What import might this affair have for the answer given to the previous question?

A big takeaway was Father Martin’s graciousness in acknowledging that Theological College made a decision about his invitation based not on his talk, but because of the hostility their staff was encountering.

I want to reiterate what I said in my public statement. Theological College is a different institution than the University. We have our own speaker policy, and under it Father Martin has been invited and spoken a number of times. Theological College is a seminary, and it might very well want to have a different speaker policy than the University, just as it has a different dating policy than the University. It is in the business of forming young men for the priesthood.

I also think it’s important to emphasize that the behavior of those in the fringe Church groups mirrors that of groups on the left who don’t want to hear things they disagree with. This pressure to silence people is something we see on both sides of the political spectrum. And it is a very unhealthy trend for both civic and ecclesiastical life.

CUA has received some criticism for accepting financial support from the Charles Koch Foundation by those who fear that his interests might be at odds with those of the Church, particularly things articulated by Pope Francis about capitalism and the ecological crisis. He’s set to come to your campus this week to speak at a conference hosted by the business school on “how profitable businesses can be a force for good.” What do you say to people who might be scratching their head at the invitation by the “bishops’ university”?

I’ve already seen some discussion about this invitation and I think there are a few things to point out.

Three years ago, we set out to build a School of Business and Economics that would educate students to live out the principles of the Church’s social teaching – solidarity, subsidiarity, human dignity, and the common good. This was in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, when every vice at odds with those principles was on display. We got a positive response from a variety of donors, among them the Koch Foundation.

As I’ve said before – if a donor finds that our mission and interests align with its own, we are happy to work together. Pope Francis is continually exhorting us to reach out to people to find common ground, to put the Church in dialogue with people who might not otherwise accept the fullness of the Gospel.

Many folks on the left are comfortable putting the Church in dialogue with others who don’t subscribe to the Church’s teachings on life and family, but who do overlap with us on immigration, labor unions, or the death penalty. We should also sit at the table with those on the right who find common ground with us on other issues. The tent – and the table – are big enough for this.

Charles Koch is not being invited to discuss his political leanings, or the environment, or his thoughts about the Church. He’s going to talk about hiring employees based on virtue and good habits; about how running a business that puts people first can also be profitable.

The Church’s teachings on business ethics and morality certainly overlap with his philosophy. And the Church – from Leo XIII through Francis – has supported job creation to help the poor, and entrepreneurship which strives to make products that alleviate hunger, suffering, and want. I scratch my head at those who don’t see that overlap.

So much of what a president at a Catholic university must face is, for lack of a better word, negative. Let’s get positive. What ideas are percolating out there with regard to how Catholic colleges and universities can live out their mission? I know many in the pro-life movement, for instance, have been calling on universities to be more formally and informally supportive of pregnant students–thus reducing the social pressure and stigma that contributes to many abortions. But that’s just one possibility. What’s in the pipeline that is positive and hopeful?

A university’s Catholic identity can’t be confined to its theology department or its campus ministry office. It should be expressed in all its operations. A university should make it easier for students to be happy and to choose good things. That’s why we moved back to single sex residence halls. It’s why we support pregnant students with residential options. It’s why we make every effort to reduce our impact on the environment in our buildings and with green initiatives.

But the Catholic identity of a school should also be lived out in all of its academic programs. It’s not enough to “put them in dialogue” with theology (as the Land O’Lakes Statement said). We should build great English departments, physics departments, art departments informed by the Catholic intellectual tradition. We should want our students to be educated in the fullness of the tradition, and to build and create beautiful things as well as good things.

When I teach my masters level course in theological ethics, we spent a lot of time thinking about the problems you’ve addressed in this interview, and about how those of us with theological commitments should respond. To simplify for the sake of asking a question of reasonable length, one might go in a “Benedict Option” direction, focusing more on the health and vigor of own religious communities and spending less time crafting and translating a message for “the world.” Or we could focus more on engaging with those who are claimed by very different traditions of thought, trying to be salt and light for a world in need of the Gospel. With the caveat, again, that the reality is more complex than these two options allow, do you feel pulled in one of these directions more than the other?

I think of the various religious communities within the Church. There are contemplative orders (Carmelites, Trappists) whose life is dedicated to prayer and contemplation by removing themselves from the world. There’s a place for those orders. There are Missionaries of Charity who are out on the streets of Calcutta. There is a place for those who like the Benedict Option – to withdraw in order to preserve.

Catholic University was founded by Pope Leo XIII and the bishops for a different reason – to engage the political and cultural questions of the moment, to help shape the American culture along with the Church. That’s why they chose Washington, D.C. for our location. It’s also why we were initially established for graduate studies. The Church has a missionary character to it. Catholic University’s own mission is to educate students in various disciplines – politics, architecture, law, to bring the best of the tradition to the questions and challenges posed to the human family today.

Pope Francis stood on the steps of the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception two years ago overlooking our campus. He told our University and the 30,000 people gathered for Mass to “go out” as missionary disciples, taking the motto of St. Junipero Serra as our own: “Siempre adelante.”

RELATED: CUA president says Pope Francis fosters new look at Church authority and higher education