Editor’s note: Patrick Deneen is an Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame. His new book is Why Liberalism Failed (Yale University Press.) Charles Camosy spoke with Deneen to unpack some of the arguments in the book, and their consequences for Catholic thought about public life.

Camosy: When you say that “liberalism has failed,” you don’t mean that liberalism–as opposed to conservatism–has failed. Can you say more about what you mean by liberalism?

Deneen: By “liberalism,” I mean the political philosophy and the resulting political institutions, practices and beliefs that dominate the governments and societies of much of the western world. Its founding fathers were philosophers like John Locke, and in the United States, the architects of our Constitutional order. But I also include in their number those considered to be “progressives,” such as John Stuart Mill, or in the United States, John Dewey.

Most of our political debates pit “classical” against “progressive” liberal visions, holding the two views as diametric opposites and thus circumscribing the whole of our political imagination. An ambition of my book is to show the deeper continuity within even these different iterations of a single philosophy, particularly regarding the primacy of individualism, support for a centralized state, a hostility to culture, the undermining of liberal education, and a deep suspicion toward more local forms of democratic practice and self-governance.

Can you share a couple cultural markers or moments that led you to come to this conclusion?

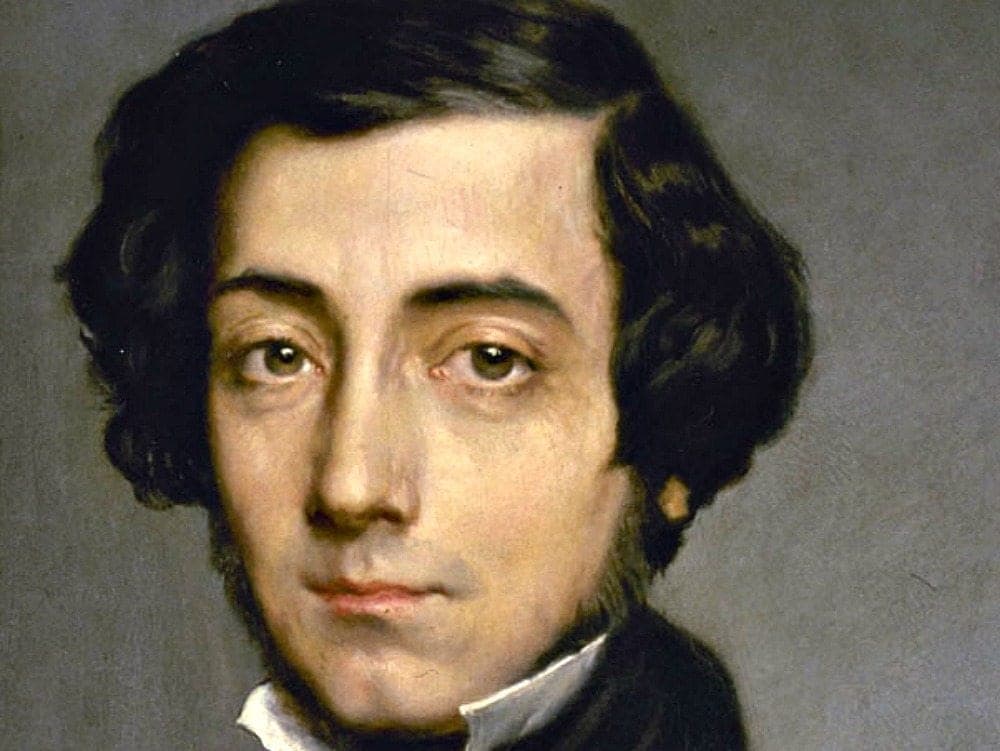

I am guided by Alexis de Tocqueville in my assessment of the course of liberal democracy, who observed that as democracy becomes “more itself,” it becomes “less itself.” Thus, the end station of democracy, according to Tocqueville, was despotism.

What I seek to describe is a gradual but accelerating “realization” of a set of philosophical beliefs that have transformed practices, making us more fully liberal over time, and as a result, giving rise to a slow realization that its success leads to its own set of systemic failures. My thesis is that liberalism has failed precisely at the moment that it has succeeded, but that realization only comes with the gradualness comparable to the rising temperature of the water that will gradually boil the frog alive.

Much of the strength of liberal democracy was due to pre-liberal inheritances that liberalism’s architects took for granted, but which have been gradually drawn down without replenishment. One example I would offer is the state of higher education today: the death of liberal education being advanced both by the liberal Left (in the form of identity politics) and the liberal Right (in its emphasis on education in the service of the economy) is simultaneously and very effectively killing the liberal arts, or the education believed for much of our history to be fitting for free people.

For me, the deepest and the saddest irony is that the regime whose name is etymologically drawn from the word “liberty” today advances a servile education suitable for people resigned to inhabiting biological “identities” and subject to irresistible economic forces, not free citizens.

Why do you think so many liberals fail to understand that liberalism, rather than a neutral political and ideological space, is a particular ideology and worldview?

Liberalism has shrouded its substantive commitments behind a veil of neutrality, although some of its classical and contemporary philosophers and defenders are forthright about those substantive commitments. But, in practice, liberalism’s advance is somewhat comparable to what happens in Economics courses: the textbook definition of basic human motivation according to economic theory is maximization of one’s utility – one’s interest and advantage.

While apparently merely a description, sociological studies have shown that students who take multiple economics courses are more likely to act more selfishly than before they took the course or in comparison to students who don’t take economics courses. In a more pervasive way, liberalism advances by positing the belief that humans exist in a state of nature as autonomous, disconnected, wholly free and rights-bearing creatures.

But what is claimed to be merely a description of human nature over time becomes an aim and goal of liberal society itself, gradually but ineluctably shaping people in the image of what it merely claims to describe. Thus, we increasingly see a liberal people defined by absence of interpersonal commitments, whether marriage, family, children, or memberships in longstanding cultures or a religious community.

Further, where commitments are taken on, they are subject to perpetual revision — whether through divorce in the matter of marriage, abortion in regard to children, or church shopping or the rise of “Nones” in the case of religion. Such people are driven above all by demands of consumption and money-making, claiming the right to self-definition while abandoning any longstanding cultural practices of self-limitation, which become increasingly regarded as unjust and unjustified limitations upon one’s freedom and autonomy.

More ironically still, a massive growth of the state is required to make this experience of individualism possible, thus enthralling purportedly free subjects to a pervasive political order.

How have Roman Catholics–and even Roman Catholic moral and political theology–accepted certain aspects of liberal ideology? What might this mean for the Church as liberalism fails?

Tragically, at least in America but perhaps more pervasively in the West, Catholicism has come increasingly to be defined by and experienced as the two political iterations of liberalism, whether “classical” or “progressive.” Rather than offering a distinct alternative, many Catholics have come to understand their faith through the lens of these dominant expressions of liberal philosophy.

One practical effect of this re-shaping of American Catholicism has been a willingness to give a “pass” to whichever part of the individualist liberal agenda that is advanced by your side, whether ideological capitalism on the Right, or abortion, divorce, and homosexual “marriage” on the Left.

Many of the attacks on my writings have come from “conservative” Catholics who completely disconnect their fundamental and defining opposition to abortion with their unceasing support for an economic system that places primary emphasis upon consumption, waste, individual choice, and institutionalized discontent.

Similarly, those who are most likely to insist on greater social responsibility in our economic lives insist (for example) when it comes to family matters, the untrammeled right to divorce and abortion. What should not surprise us is that it’s the liberal individualist positions of each side that have been politically successful, while the more “Catholic” side consistently loses.

Catholicism rejects both anthropological individualism and collectivist statism, but today we are divided into Catholic tribes who by default advance one or the other as a central political project.

Historically, the destabilization and failure of overarching political movements and structures have been bad news for the cultures which rested on them. What comes after failure of liberalism in the short term? In the long term?

I argue in my book that liberalism advances an “anti-culture”: whether through blandishments of the market or the power of the state, it seeks to weaken and eviscerate culture and replace it with a homogenous anti-culture of “free” people who consume pre-packaged, monetized “popular culture,” but no longer live in actual cultures of memory and tradition.

Inasmuch as we see deep instability and forms of systemic failure in our politics, this dysfunction occurs not in spite of an otherwise healthy culture, but to a great extent because of the destruction of culture and its replacement with an anti-culture. As cultural norms, practices and forms of belonging are eviscerated, informal codes must be replaced by legal systems and state enforcement of legalized directives.

Growing segments of the population view such legalization of nearly every sphere of life as an illegitimate exercise of centralized state power, and what might otherwise be reasonable political debates become existential battles in which control of the state becomes the main purpose of life.

For this reason, we are seeing the failure of liberalism not because it has yet to be realized, but because of its success. The challenge for us — I would especially direct this encouragement to fellow Catholics — is the cultivation of sustaining culture that, among other things, will lessen the importance of our dis-eased obsession with politics and the state.