BELFAST – For anyone who’s ever visited Belfast, it’s actually a captivating and charming city. Alas, its main claims to fame are calamities, above all “The Troubles” — a period from the late 1960s to the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 in which Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland butchered one another with abandon.

BELFAST – For anyone who’s ever visited Belfast, it’s actually a captivating and charming city. Alas, its main claims to fame are calamities, above all “The Troubles” — a period from the late 1960s to the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 in which Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland butchered one another with abandon.

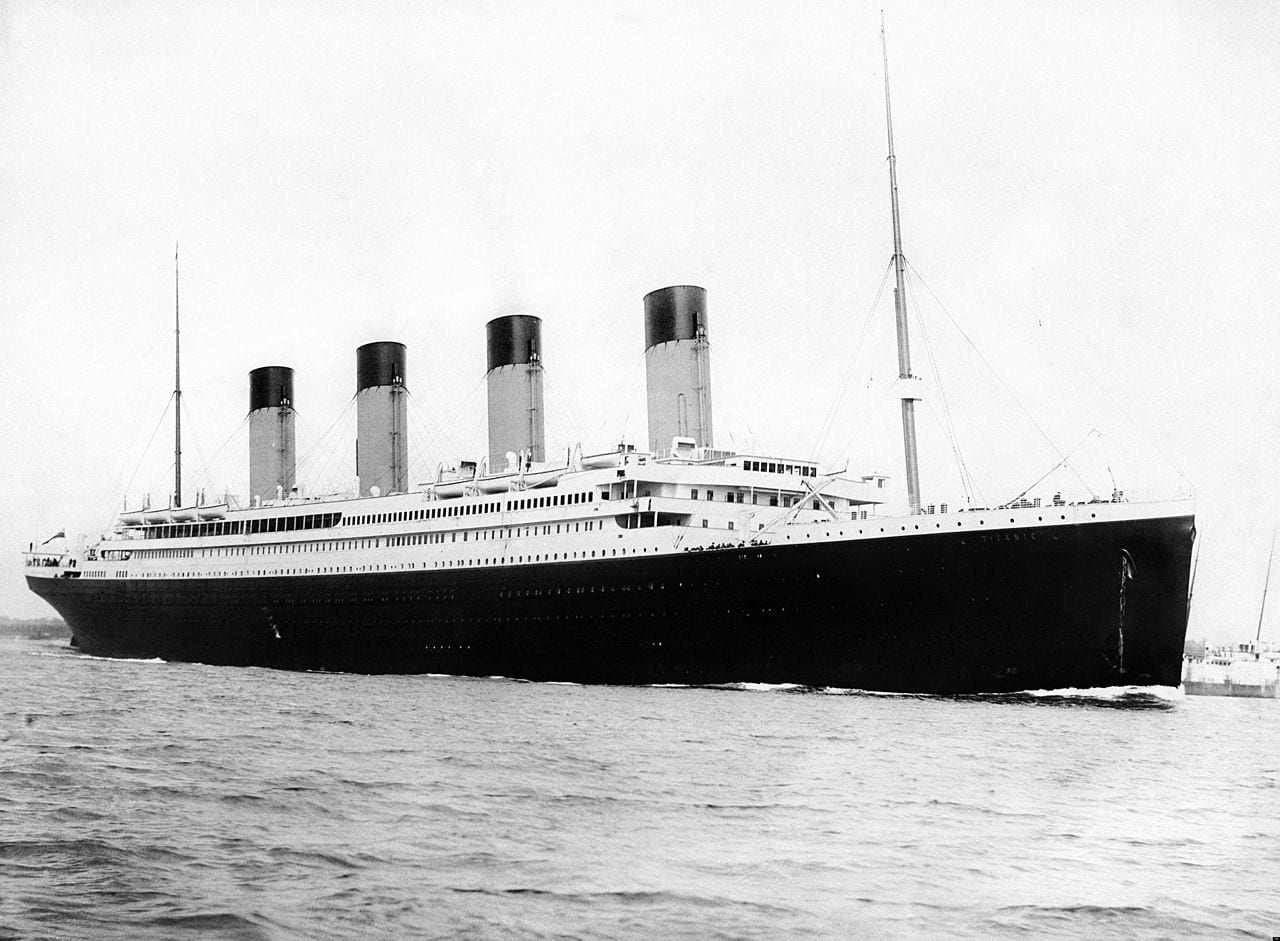

There’s also, however, another disaster forever linked to Belfast – the Titanic. It was here, once the “shipyard of the world,” where the massive luxury liner was designed, built and launched before it eventually sank on April 15, 1912.

At first blush, the difference between those two dubious chapters in history might seem to be that the former had clear religious overtones, while religion had nothing at all to do with the latter.

The Titanic, after, all, didn’t fall victim to religious terrorism or sectarian strife, but to the penny-pinching greed of its parent company, the White Star Line, as well as the hubris of company chairman Robert Irsay and the ship’s captain, Edward Smith.

Yet upon closer inspection, there’s a clear religious subtext to the Titanic story, both in terms of the distressing nature of the Protestant/Catholic divide of the day but also the glimpses of heroism one saw as the massive ship reached its fate.

Depending on how things play out, one day there may even be a Titanic saint.

Yesterday, I, along with Crux’s Inés San Martín and Claire Giangravè, set out to discover that religious dimension to the story, visiting the new “Titanic Belfast” Museum in the city’s old shipyards, erected on the very site where the ship was built and launched. (One can even stand where the front bow once was and have what our guide cheerily called a “Jack and Rose” moment, referring to the famous 1997 James Cameron movie.)

When it sank, the Titanic was carrying 2,208 people, passengers and crew. There were three Catholic priests and five Protestant clergy among them, every one of whom died – a lesson about the ecumenism of tragedy which, unfortunately, it took Northern Ireland virtually the entire rest of the 20th century to absorb.

The three priests were:

- Father Juozas Montvila of Lithuania, who was 27 and fleeing Tsarist oppression of Catholics in Ukraine where he’d been serving.

- Father Josef Benedikt Peruschitz, a German who was 41.

- Father Thomas Roussel Byles, who was 42 and British. Byles was a convert to Catholicism, who took the name “Thomas” in homage to St. Thomas Aquinas.

At one point a fourth priest was also supposed to be on board – Father Francis (Frank) Browne, a newly minted priest planning to enter the Jesuit order and also an accomplished photographer. His uncle, Bishop Robert Browne, had given him a two-day ticket on the Titanic to sail from Southampton, the ship’s first port of call, to Queenstown, its third.

(“Queenstown,” by the way, was the city’s name under British rule of Ireland. After 1920 it reverted to “Cobh.”)

Father Browne spent his time aboard snapping photos and chatting with fellow passengers. He charmed an American couple who volunteered to pay for the rest of his passage to New York, and Browne fully intended to accept. His plans were cut short, however, when the ship docked in Queenstown and the young priest was handed a telegram from his uncle.

The message was to the point: “Get off that ship now.”

To this day, it’s not clear whether Bishop Browne simply meant it was time for his nephew to get to work, or if he had some inkling of what was to come. In any event, Father Browne complied, which is how he came to be the last person ever to snap a photograph of the ship as it sailed out to sea.

(As a footnote, Bishop Browne was the prelate who would later lead the funeral Mass for the Irish victims of the Titanic.)

The other priests all perished, with witnesses later reporting that they had helped women and children into lifeboats and refused offers of a space for themselves, then later prayed with people after the lifeboats ran out. Their bodies were among the hundreds never recovered.

Byles, the English priest, was on his way to New York to officiate at his brother’s wedding. Later, the brother and his wife visited Titanic survivors to understand how Byles had spent his last hours aboard ship.

They learned that when he said his final Mass, on April 14, Byles had preached a homily about the new life in America that lay ahead for most of his on-board congregation. Following the collision, they were told, he was twice offered a seat on a lifeboat as a man of the cloth and refused both times.

Instead, Byles made his way down to the steerage section, escorting third-class passengers up to the main deck and helping those women and children reach safety too. Survivor Bertha Morgan, whom Byles helped get a seat, later recalled hearing him praying aloud as her lifeboat pulled away.

At the very end, Byles prayed an Act of Contrition before a crowd of hundreds with ocean water already at their feet, offering them absolution – a remarkably ecumenical gesture for the early 20th century, set against a backdrop of a shared fate.

Months later, William Byles and his wife traveled to Rome and met Pope Pius X during an audience, who reportedly referred to the drowned priest as a “martyr for the Church.”

Today there’s a push to see Byles formally declared a saint, which is led by the pastor of his former parish in England, Father Graham Smith.

“I believe that Fr Byles’s actions show us that heroic acts of virtue really do happen,” Smith said in 2016 about why he decided to launch a sainthood cause. “He is an example of how selfless giving is possible even in times of serious distress.”

Beyond those individual narratives, there’s also a clear religious dimension both to how the Titanic began, and how it ended.

In early 20th century Belfast, the Protestant/Catholic divide was ubiquitous. The White Star line at the time had a notoriously hard line on hiring Catholics, and, although there were blue-collar Catholics who worked in the shipyard (they weren’t banned completely until the 1920s), there were certainly no Catholics on the 22-man drafting team for the great ship or at the management levels of its parent company.

The religious tensions that defined the city also reached down into the crews that built the Titanic. Protestant workers were in the habit of scrawling “NO POPE” in tall letters on the hulls of ships under construction, and urban legend in Belfast still has it, 106 years later, that each rivet hammered into the Titanic had “F… the Pope” stamped onto it.

The Catholic/Protestant breach also helped shape who lived and died as the Titanic went down.

In percentage terms, the most likely group aboard to survive the shipwreck were first-class passengers, the most elite of whom paid the equivalent of almost $100,000 in today’s currency to book one of the “parlor suites.” Those travelers tended to be British and American, and almost exclusively Protestant.

Aside from the crew, the most likely people to perish were third-class passengers who had scraped together the £6 that a ticket cost, about $500 today, and who were not taking a pleasure cruise but leaving their homes forever to seek opportunity in the New World.

Those passengers were mostly Irish and Catholic, meaning that religious division aboard the Titanic was literally a matter of life and death.

Yet amid those reminders of prejudice and its ugly consequences, it’s also worth remembering that it wasn’t just Catholic priests who behaved with heroic virtue. Five Protestant clergymen also perished, all having refused offers to board lifeboats just like their Catholic counterparts.

One of those clergy, Reverend William Lahtinen, was a Finnish immigrant to the United States and a Lutheran pastor. He’d sailed back to Finland following the death of a child and was attempting to make his way back to America when he boarded the Titanic in Southampton. He calmly chose to remain aboard ship, delivering prayer and comfort for Catholics and Protestants alike.

Scottish Pastor John Harper reportedly swam around after the ship went down, asking people if they were saved and offering to pray with them. When he put that question to one young man, the story goes, the young man shouted back “No!” whereupon Harper took off his lifejacket and tossed it to him, saying, “Then you need this more than me.”

(The young man was one of just a handful of survivors rescued at sea; Harper’s body was never found.)

In other words, in religious terms the Titanic appears exactly the same story it is at every other level – a gaudy mix of heroism and cowardice, selflessness and greed, vice and virtue. Perhaps that’s why, as our museum guide reminded us, there’s a “deep-rooted connection between Belfast and this mighty ship” – because if any place on earth understands that religion can bring out both the best and the worst in humanity, it’s probably here.