“No Greater Love” is available on DVD from Ignatius Press and can be purchased via Amazon.

At St. Charles Square in North Kensington, in west London’s trendy Notting Hill neighborhood, is an outpost of Mount Carmel: the Monastery of the Most Holy Trinity, home of a cloistered community of Discalced Nuns of the Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel.

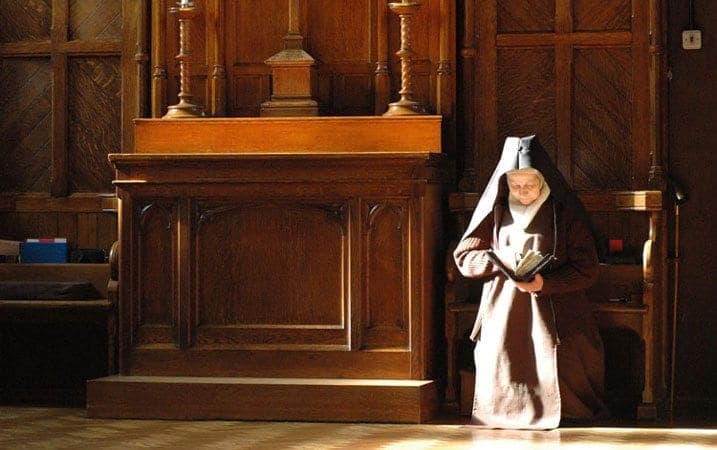

Not far the bustling, touristy street markets of Portobello Road and Golborne Road, the Carmelites live in silence and contemplation, embracing lives of poverty, chastity, and obedience. Every day, locals and tourists walk past the high convent walls with no inkling what goes on on the other side.

Filmmaker Michael Whyte actually lived across the square from the monastery for years without realizing it was still occupied. One day, he heard the monastery bell calling the sisters to prayer.

It took Whyte a mere 10 years to persuade the nuns to allow him to film inside the monastery. (That’s six years less than Philip Gröning waited for permission to film “Into Great Silence” at the Grand Chartreuse monastery in the French Alps!)

“No Greater Love,” filmed over the course of a year or so circa 2008, presents the lives of the nuns as a rhythm of work and prayer as well as recreation. Images of the Carmelites kneeling in silence on the parquet choir floor are intercut with shots of a nun in the courtyard scrubbing the stained glass windows with a long-handled squeegee.

In the kitchen, a nun mixes batter and ladles it onto hot irons that press it into platter-sized, disk-shaped sheets, like oversized, rigid tortillas. At first, it may not be clear what she’s making — until the wafers go into a punching machine that slices through a heap of them at once, each time issuing scores of Communion hosts.

Earlier in the film, we see the nuns receiving Communion at Mass. How does it affect the experience of Communion when baking and forming Eucharistic hosts is part of your daily work? The nuns of Most Holy Trinity make millions of hosts a year, supplying churches throughout the Archdiocese of Westminster, including the cathedral.

Compared to the Carthusian monks of “Into Great Silence,” the English-speaking nuns of “No Greater Love” are less exotic and more familiar. They sing well-known liturgical settings and allow Whyte to interview them. They cite the English Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins and the Jewish existentialist philosopher Paul Landsberg. They talk about faith, silence, prayer, liturgy, and spirituality, but also about their struggles and dark times.

The interviews are one of the key differences between Whyte’s rewarding documentary and the pure cinema of Gröning’s more austere, impressionistic film. There are also obviously convergences, given the subject matter. In both films, we see the community sharing a common meal while the rule of the order is read aloud. Toward the end of both is a lighthearted scene of recreation, in this case showing the nuns engaged in simple line dancing.

But Whyte’s subjects reveal themselves to us in ways that Gröning’s don’t, talking about everything from the design of habits and how to dispose one’s habit while gardening, to St. John of the Cross and the dark night of the soul. One sister talks about common but misleading, mutually exclusive ideas of religious life, which she says is neither carefree nor oppressive. Another talks about how they bring into their prayers the people in the world around them who find no time in their busy routines for prayer for themselves.

An awareness of death and mortality hangs over “No Greater Love,” something absent in “Into Great Silence.”

Gröning’s film achieves a transcendental state of timelessness and suspension; one of the monks even talks briefly about not fearing death, but the film never confronts us with its inevitability.

In contrast, “No Greater Love” shows us graves of generations of nuns marked by Celtic crosses and other monuments. The shadow of death lies across a number of the interviews. The film’s most inspired stroke lies in the way the death of one of the older nuns is juxtaposed with the greatest expression of the community’s resurrection faith, and the narrative thread that is the heart of the film. Christ rises from the grave; the Christian is committed to the earth. Each of these is, in some way, the reason for the other, and gives the other its meaning.

Like the blind monk in “Into Great Silence,” the Carmelite prioress talks about not being afraid of death — but then, in a disarmingly candid moment, she acknowledges with a chuckle that there’s always the thought that the atheists could be right and there is nothing, in which case at least there won’t be anyone to tell her so. And if she’s right, there will be someone to meet her.

When Whyte ventures to ask the nuns about the dark night of the soul in Carmelite tradition and what their experiences of it might be, one immediately laughs, as if words are useless.

But she does talk about it, as does the elderly prioress, with whom we spend the most time. One of them went for about two years with no sense of God’s presence or even of his existence; the other spent about 18 years afflicted by a sense of divine indifference and neglect. At the far end of these experiences, which make sense only in retrospect, is the loss of false images of the divine and a deeper and truer knowledge both of God and of oneself.

“No Greater Love” begins with a literal wake-up call: a nun walking down a darkened corridor rattling some kind of noisemaker to rouse her sisters. (The clock in the next shot reveals that the nuns rise at 5:20.) The film ends with a camera movement that could just as easily been used for the opening, but in reverse: a slow zoom out of the monastery grounds and a pan over the Notting Hill skyline, situating the world we never knew in the world we take for granted.

In doing so, “No Greater Love” invites us to look at our own world with new eyes, and consider what greater love we might bring to the rhythms and routines of our own lives. It’s a wake-up call we all need to hear from time to time.