ROME – For all those concerned with a rising tide of anti-Christian persecution around the world, certain things about the nation of Pakistan may seem blindingly obvious: That Shahbaz Bhatti, for instance, should be declared a martyr and saint, and that a death sentence for Asia Bibi should elicit outrage and condemnation.

For anyone who thinks such things are simple matters of black and white, a conversation with Pakistan’s new cardinal is a refreshing reminder of the complexities of the real world.

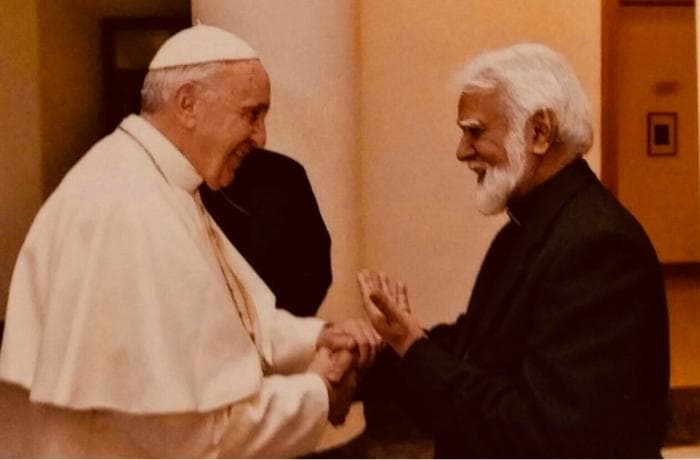

Cardinal Joseph Coutts, who’ll be inducted later today by Pope Francis into the Church’s most exclusive club, voiced caution on both Bhatti and Bibi in a conversation with me on Tuesday – not really because he has any doubts about the merits of either case, but because he has to live with the consequences of whatever he says or does, and those offering confident commentary from the outside don’t.

Bhatti, the lone Christian minister in Pakistan’s national government, was assassinated in 2011 for his passionate advocacy of minority rights and his opposition to the country’s “blasphemy laws,” which establish criminal penalties, including death, for either insulting the prophet Muhammad or desecrating the Qur’an.

Bibi, an illiterate Catholic mother and farm worker from the Punjab, was sentenced to death by hanging in 2010 for allegedly insulting Muhammad and has been on the country’s death row ever since, as various hearings and appeals have worked their way through the Pakistani legal system.

“He was Catholic, a practicing Catholic, and he wanted to move parliament to do something about the blasphemy law; if not abolish it, then modify it,” said Coutts, the Archbishop of Karachi.

“He started receiving threats, and some friends started telling Shahbaz, you better take these seriously, because these guys don’t hesitate to kill,” Coutts said. “He said, ‘Why? I’m not doing anything wrong? I’m speaking for the truth, why should I run away? Why should I leave the country?’ So he didn’t and he paid for it with his life. He stood for the truth.”

Despite that ringing praise, Coutts stopped short of declaring Bhatti a martyr or saint-in-waiting.

“I’m not saying he’s a martyr or that he’s been canonized, I’m just trying to explain what it was,” Coutts said. “He was killed for that, for standing up for what is right.”

“You’ve got to examine the life of the person, so the whole purpose of the process is this,” he said. “So it’s not so easy for me to say yes he is a martyr, or no he’s not.”

On the prospect of eventual sainthood, all Coutts would say is, “It needs to be seriously looked into.”

The same restraint ran through his discussion of the Bibi case.

Referring to outsiders who wonder why the bishops or the Catholic establishment in Pakistan hasn’t done more to press for Bibi’s release, Coutts suggested those are lazy judgments born of not having to live with the consequences.

“Especially you in the West, you don’t know what the atmosphere is like. Shahbaz was killed as a parliamentarian just because he said he wanted to put it up to parliament, he was killed for it,” he said.

“There have been judges, at least one that I know of, who was killed because he acquitted a twelve-year-old boy who was accused of blasphemy,” Coutts said. “He was accused of having written something blasphemous on the wall of the mosque, and then it was proved that the boy couldn’t have written those words because he was nearly illiterate. So, the good judge said, ‘Case dismissed.’

A few months later he was shot dead in his office.”

“You’ve got to understand the atmosphere, the kind of society we’re living in. These extremists, they don’t hesitate, not only to kill, but also to be killed. They don’t hesitate,” Coutts said, by way of explaining why discretion is sometimes the better part of valor.

Coutts said he’s not primarily thinking about his personal safety, but also the fallout for the people he serves.

“What I say will not only affect me. When you’re in a certain position, what you say affects who you represent. And we’ve seen enough of that,” he said.

“Take these blasphemy cases, the so-called ‘little cases.’ It’s the whole area where you live … that whole area could be attacked by a mob, and they wouldn’t go knocking on the door asking ‘Which is the house?’ They would just go attacking everywhere the Christians are living,” he said.

“You are endangering others as well. It’s not a question of just being bold, it’s a question of being discreet,” he said.

None of this is to suggest that Coutts is in denial about the existential threat facing his country.

“[There’s] this new form of militant Islam, and they want to see Pakistan as a purely Islamic state,” he said. “Much of Pakistan is moderate, we are a democracy, but these kind of people don’t believe in democracy, they say it openly,” he said.

“They say democracy is the will of man, you’re choosing your leader, [but] they are doing the will of Allah. So they don’t believe in separation between church and state. They say Islam is a total way of life, so they want the Islamic system,” he said.

So if Coutts exercises restraint from time to time, it’s not because he’s blind to what minorities and Christians are up against in one of the world’s largest Islamic states, and one of its nuclear powers.

Instead, it’s because he’s trying not to make a bad situation worse – something that Westerners trying to reach judgments about Pakistan and its Christian community might do well to remember.