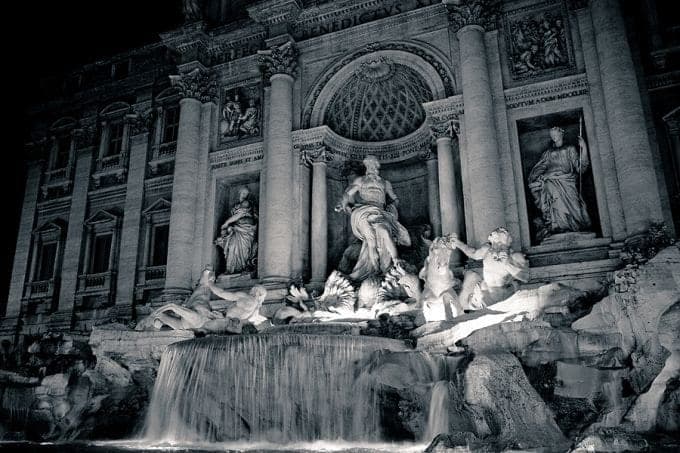

Anyone who’s ever been to Rome on holiday – for that matter, anyone who’s ever seen movies such as “Three Coins in the Fountain” – knows what you’re supposed to do at the city’s famed Trevi Fountain. You toss in a coin and make a wish, hoping that good fortune will be yours.

Last year, roughly $1.7 million worth of coins was tossed into the fountain. What people performing that traditional act may not have known is that since 2001, the proceeds have gone to fund the Catholic Church’s charitable activity in the city, through an arrangement among the city government, the power company ACEA that administers the fountain, and Caritas, the Church’s charitable arm.

Caritas uses the money for direct service to the city’s poor, including soup kitchens, temporary shelters and housing for impoverished families. The amount accounts for roughly 15 percent of Caritas’s annual charitable budget.

As of April 1, however, that will no longer be the case.

Rome’s current city government led by the left-wing populist “Five Star” movement under Mayor Virginia Raggi has decided to take back the funds, using them to pay ACEA’s bill to maintain the fountain as well as “social projects” and “routine maintenance of cultural patrimony.”

Rome is perpetually broke – in 2016, public debt was estimated at a staggering $14 billion – and the move with the Trevi Fountain is a small part of a larger effort to find new sources of cash.

For the past 17 years, what’s happened is that personnel from ACEA have periodically emptied the coins out of the fountain and placed them in sacks, which are turned over to officials from Caritas in the presence of city police. Caritas workers then dry them off, count them, and deposit them in the bank. Three times a year, Caritas has furnished the city an accounting of how much was collected, which for several years running has been in excess of $1 million.

Now, those collections will go to city officials to be deposited into the ordinary public budget.

On Friday, the official newspaper of the Italian bishops’ conference, Avvenire, made clear that the Church isn’t exactly turning cartwheels over the decision.

“In sum, the entire charitable activity of Caritas, which was carried out thanks to the coins from the Trevi Fountai at zero cost, before long will be hit with costs that are far heavier,” journalist Luca Liverani wrote.

“Experience teaches that in private social activity, virtually all the resources are spent for the purpose for which they’re intended, in this case helping the poor,” Liverani wrote. “When they end up in public hands, often those proportions are inverted, and a good portion of the funds is wasted in the streams of bureaucracy rather than arriving at the poor.”

In one sense, the contretemps over the Trevi Fountain is merely the latest chapter of a story that’s been underway for some time, with the Italian state at various levels increasingly assertive about revoking traditional privileges and demanding that the Church pay its fair share.

In 2012, then-Prime Minister Mario Monti pushed a plan to remove the Church’s tax-exempt status, especially on commercial enterprises operated by Catholic entities – monasteries, for instance, that market their own wines, or convents that have converted unused space into B&Bs. Such moves have been supported by every government that’s followed, irrespective of political orientation.

Last year, the European Court of Justice ruled that the Vatican must pay the Italian state $4.5 billion in back taxes for the period 2006 to 2011. While few observers seriously believe that’s going to happen, it’s another sign of mounting political frustration with what’s perceived as special treatment for the Church.

The Trevi Fountain case reflects that trend, in that the revocation of funds is being carried out by a mayor from the Five Star movement, which is also part of the country’s ruling coalition at the national level. Recently the head of the Italian Senate’s finance committee, who also comes from the Five Star movement, applauded the European sentence on taxes and insisted that the Catholic Church must foot the bill for its real estate properties “like everyone else.”

According to the latest polls in Italy, the Five Star movement enjoys roughly 29 percent popular support, with its governing partner, “The League,” garnering 31.5 percent. Together that’s over 60 percent, easily enough to command majority backing for most initiatives.

Granted, the spigot of public support for the Church in Italy isn’t in any danger of being turned off soon. Through the country’s church tax system, the otto per mille, the Church still collects a tidy sum in excess of $1 billion every year from the income tax payments of Italian citizens.

Still, the fact that it’s now perceived as politically advantageous to try to limit public support for the Church illustrates a couple key facts of life in the early 21st century.

First, due in large measure to scandals of various sorts, the institutional church has lost a great deal of credibility. The personal popularity of Pope Francis has not been enough to offset that gap – if anything, Francis’s profile may have exacerbated it, since the perception usually is that Francis is anti-establishment himself and often distrustful of ecclesiastical bureaucracy.

Second, the loss of popular support means that even in traditionally stalwart Catholic nations such as Italy, the Church will be increasingly unable to count on public financing for its activities. It will have to learn to make do with fewer resources, with a greater share generated by voluntary private contributions.

In other words, it will have to rely to a greater degree on its rank-and-file membership – which perhaps suggests that attention to the concerns and grievances of that membership won’t just be a pastoral imperative going forward, but more and more a financial one as well.