ROME –Whatever else Pope Francis’s decision Monday to open the archives from the pontificate of Pius XII in 2020 may mean, there’s one preliminary conclusion that seems take-it-to-the-bank, no-doubt-about-it, slam-dunk certain.

Here it is: Opening the archives will not – indeed, by definition, cannot – settle the historical controversy about Pius XII and his alleged silence during the Holocaust.

That’s because the debate is counter-factual, pivoting not on what Pius did or didn’t do, but rather what he should have done.

Should Pius XII have publicly denounced Hitler? Should he have threatened to excommunicate anyone involved in the mechanism of the Holocaust? Should he have pressured the Allies to liberate Nazi extermination camps earlier? Should he have offered himself in ransom for German prisoners in Rome after the 1943 occupation of the city, or come up with some other dramatic gesture to register disapproval?

Answers to those questions involve subjective judgments about what would have produced the best results in a complicated set of circumstances – whether fortune would have favored the bold, or discretion was the better part of valor – and, alas, there’s no “smoking gun” in anyone’s archives that will provide conclusive resolution one way or the other.

Moreover, the debate over Pius XII is also a moral one, and as anyone who’s ever taken moral philosophy or basic logic knows, one cannot deduce an “ought” from an “is.” You can pile up all the historical facts you like, but in themselves they won’t tell you what Pius or anyone else ought to have done.

By now, the basic data points about Pius XII and the Holocaust are wearily familiar to anyone who’s followed the back-and-forth since 1963, when Rolf Hochhuth published his play “The Deputy” and thereby launched the accusation that the pontiff was complicit, at least through his silence, in the mass extermination of Jews.

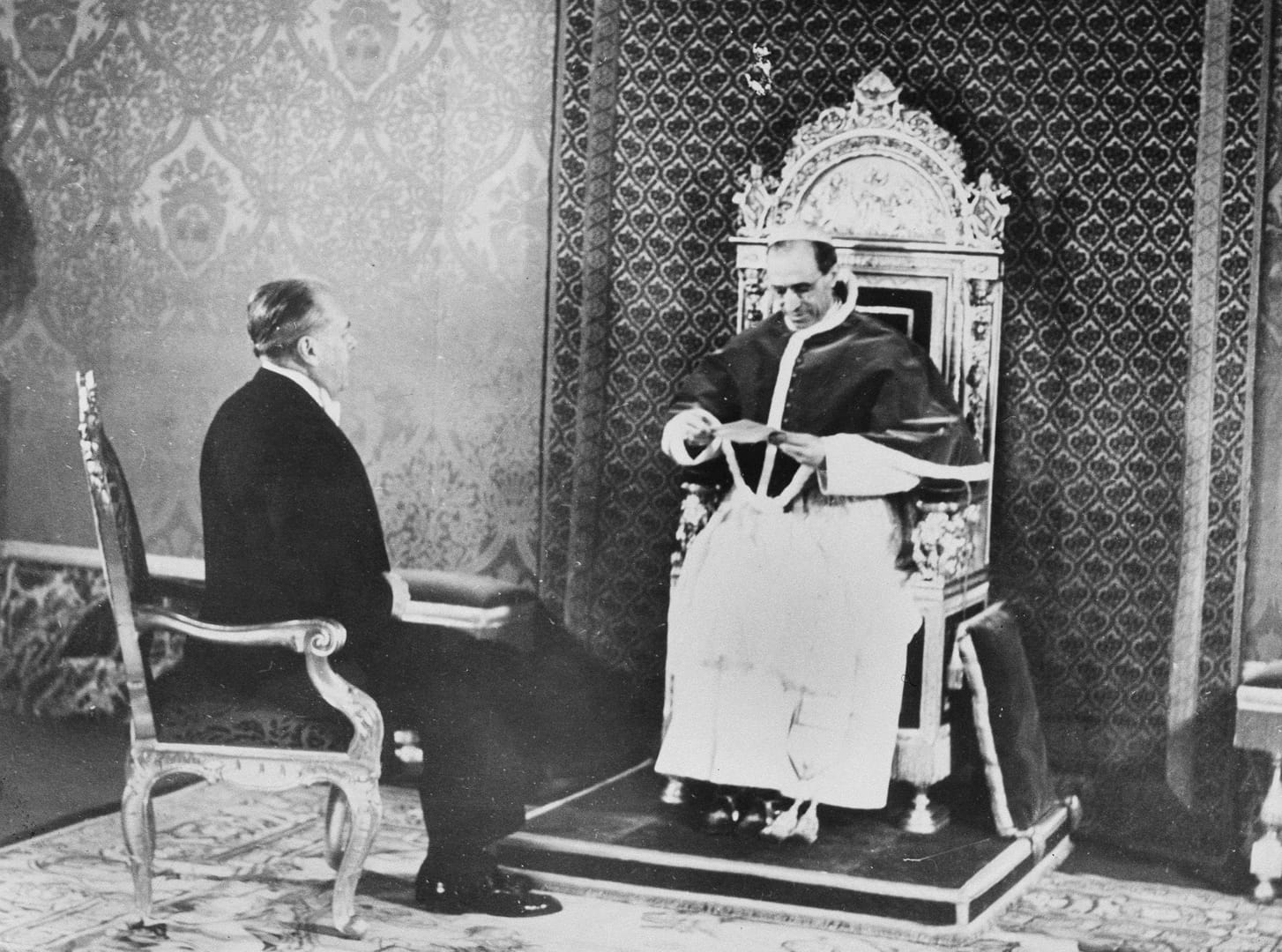

Prior to that point, it’s well-established that Pius XII enjoyed broad admiration for his leadership during the war years, including within the Jewish community. In 1958, for instance, then-Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir famously wrote: “During the 10 years of Nazi terror, when our people went through the horrors of martyrdom, the pope raised his voice to condemn the persecutors and commiserate with their victims.”

After “The Deputy,” however, a more critical reading of Pius’s record began to take hold, which in turn sparked an increasingly polemical body of apologetics seeking to defend the pope. The exchange came to be known as “the Pius war,” and while it’s slowed in recent years, there’s little indication that the underlying sentiments on either side have altered.

Proof that fresh data won’t really change much comes from the irony that positions about Pius XII hardened at precisely the same time the Vatican was providing unprecedented access to its records. St. Paul VI ordered the archives from the war years made public, which happened in a series of 12 volumes published between 1964 and 1981. St. John Paul II authorized an additional release of records in 2004 concerning prisoners of war.

Given that all those records have already been made public and put under a scholarly microscope, most experts are skeptical that anything new will come to light in 2020 that will really alter the calculus. (Granted, critics suspected the Vatican had “sanitized” those materials, but who’s to say they won’t lodge the same complaint this time?)

“Lovers of scoops may be a little disappointed,” said French church historian Philippe Chenaux, who teaches at Rome’s Lateran University.

“It’s not to be expected that [the material to be opened in 2020] will cause great changes in the interpretation of Pius XII and his attitude during the war,” Chenaux said.

That’s not to say that the new material won’t be of keen historical interest, but likely in other areas. As Chenaux pointed out, the late 1940s and 1950s have long been a bit of a “black hole” for researchers – there are abundant studies of the war years and of the run-up to the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), but relatively little in between.

Those years produced some of Pius’s greatest teaching documents, such as 1947’s Mediator Dei, on the liturgy, and 1950’s Humani generis, which helped open Catholic thought to evolutionary theory and the biological sciences. The period also includes some of Pius’s most important administrative moves, such as his efforts in 1953/54 to rein in France’s “worker-priest” movement, which, in some ways, would anticipate later struggles over liberation theology.

Americans will be interested in whatever the archives may reveal about Pius’s relationship with the U.S. hierarchy of the day, perhaps especially his close ties with Cardinal Francis Spellman of New York. It would be fascinating, for instance, to know what Pius really thought when Spellman turned down the pontiff’s offer in 1944 to make him the first American Secretary of State – whether Pius regretted a missed opportunity, or, as he watched Spellman move in a progressively more hardline direction, felt he’d actually dodged a bullet.

Moreover, the opening of the archives also may help clear the path for Pius XII’s sainthood cause, if only by removing one of the usual objections as to why it was “premature.” (Notably, however, concerns about records still being confidential didn’t get in the way of sainthood for John XXIII, Paul VI or John Paul II, which suggests that assessments of personal sanctity have relatively little to do with the details of ecclesiastical governance.)

In any event, what opening the archives will not bring, at least in itself, is an end to the moral dispute over the legacy of Pius XII vis-à-vis the Holocaust. Resolving that argument would require an opening of minds and hearts, not just records, and the former are generally far more difficult to unseal.