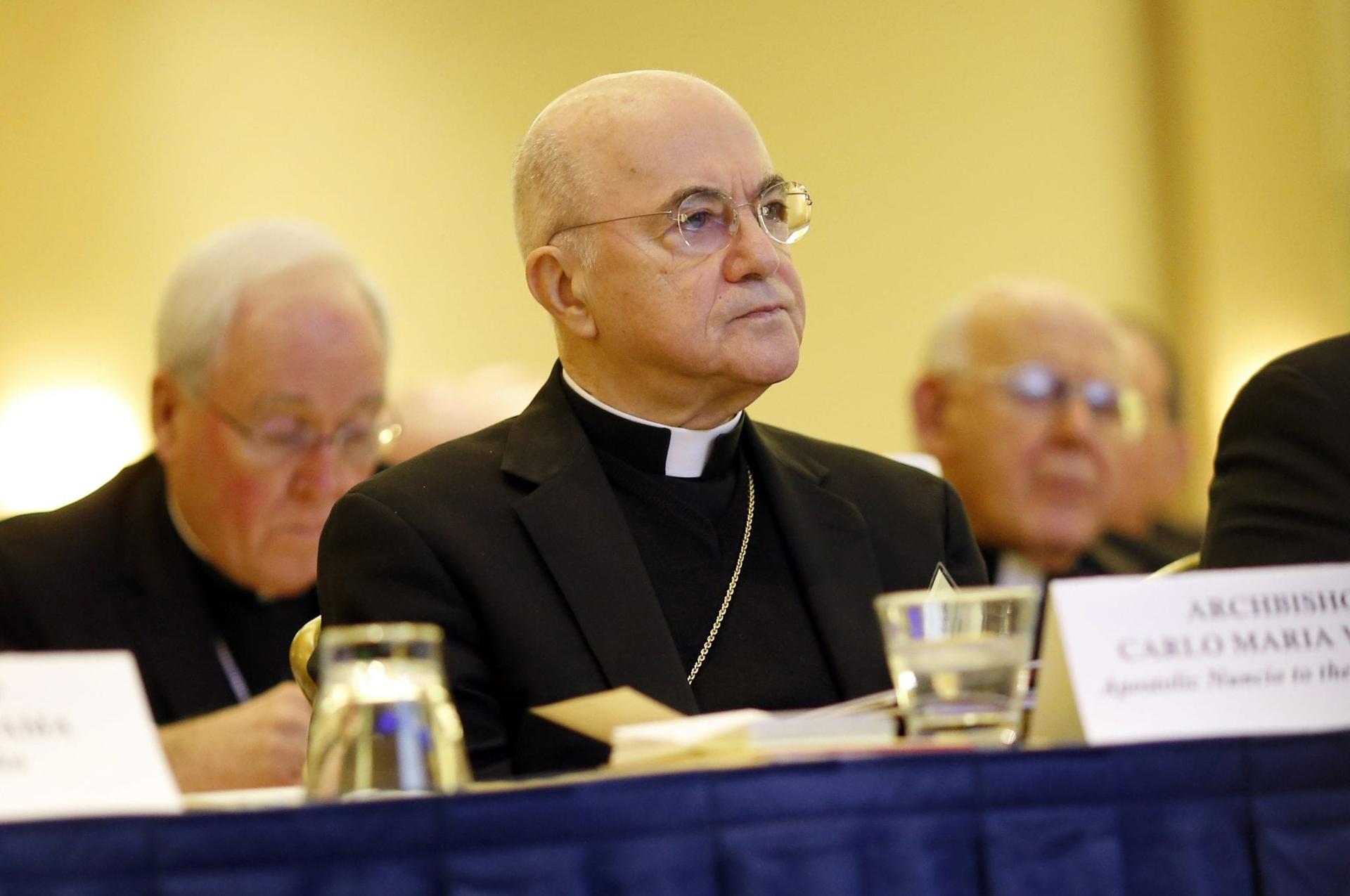

ROME – Presumably, when Italian Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò released his now-infamous statement last August claiming that Pope Francis was in on the cover-up of misconduct by ex-cardinal, and now ex-priest Theodore McCarrick, it was because he wanted to shock the system into getting to the truth.

Under the law of unintended consequences, however, it’s becoming steadily clearer that Viganò’s bombshell actually may have made it harder, not easier, to establish exactly what the Vatican knew, and when, in the McCarrick saga.

(The caveat “presumably” is obligatory, since there are countless theories about what Viganò’s real motives were in leveling his j’accuse, and finding the truth doesn’t figure especially high in some of them.)

In a nutshell, there are bishops out there – and I know this, because I’ve spoken to several – who support a thorough investigation of the McCarrick case, especially on the Vatican end, but who now hesitate to say so publicly for fear of being associated with Viganò and what’s seen as the ideological crusade against Francis he represents.

By way of a brief recap, an initial accusation of sexual abuse of a minor against McCarrick resulted in his suspension from public ministry in June. One month later, Pope Francis accepted McCarrick’s resignation from the College of Cardinals.

Then came Viganò’s 11-page missive in late August, timed to coincide with Francis’s visit to Ireland for the World Meeting of Families. In the wake of that letter, just under 40 Catholic bishops, almost all Americans, issued statements or made comments to reporters suggesting the charges in the letter ought to be taken seriously, with some adding personal testimonials to Viganò’s character and credibility.

Bishop Robert Morlino of Madison, Wisconsin, for instance, said: “During his tenure as our Apostolic Nuncio, I came to know Archbishop Viganò both professionally and personally…I remain deeply convinced of his honesty, loyalty to and love for the Church, and impeccable integrity … The criteria for credible allegations are more than fulfilled, and an investigation, according to proper canonical procedures, is certainly in order.”

It did not escape anyone’s attention that most of the bishops speaking in favor of Viganò and calling for investigation of his charges were perceived as conservatives with serious reservations about many aspects of Francis’s papacy, such as American Cardinal Raymond Burke and Kazakhstan Bishop Athanasius Schneider.

The following month, the leadership of the U.S. bishops’ conference came to Rome to propose a Vatican-sponsored Apostolic Visitation related to the McCarrick case, meaning an investigation with the pope’s backing. Francis turned down that proposal, leading to local probes in the four dioceses in which McCarrick served: New York; Metuchen, New Jersey; Newark; and Washington, D.C.

While those reviews are ongoing, most observers are skeptical they’ll yield the desired answers, since explaining who propelled McCarrick up the ladder and may have looked the other way about his misdeeds is ultimately a question for Rome.

In October, a Vatican statement indicated that Francis had ordered a review of the Vatican’s files on the McCarrick case “in order to ascertain all the relevant facts, to place them in their historical context and to evaluate them objectively.”

At the time it seemed the Vatican was gearing up for bad news, since the statement added, “It may emerge that choices were made that would not be consonant with a contemporary approach to such issues.”

To date, however, no public disclosure has been offered as to the results of that review. (Granted, it may be unlikely there’s any “smoking gun” in the archives proving that a given official actually knew for a fact that McCarrick was abusing minors and chose to conceal it, but at the very least it would be helpful to know if missed opportunities occurred, and on whose watch.)

Around Roman water coolers, some believe the silence on McCarrick is due to the fact that the outcome could stain the legacy of St. John Paul II and some of his key aides, including Cardinal Stanislaw Dziwisz, the pontiff’s priest secretary, and Cardinal Angelo Sodano, John Paul’s Secretary of State. Both men were in power as McCarrick made his way up the ladder, and both are still alive.

Others believe that the reticence on McCarrick is due to concerns that there might be some merit in Viganò’s charges – if not that Francis was directly aware of abuse allegations and ignored them, at least that he chose not to pursue the rumors vigorously.

In any event, it’s been more than five months since the Vatican promised a review of its files, and nothing has been reported. One obvious question is why American bishops, either publicly or privately or both, aren’t being more vigorous in demanding that the Vatican deliver, since they’re the ones most exposed to pastoral blowback over the failure to do so.

One answer is this: Bishops everywhere, very much including the U.S., hesitate to do anything the boss and his team might perceive as disloyal. By now, being seen as siding with Viganò is regarded by Francis allies as virtually a sin against the Holy Spirit, and unless a bishop has been living under a rock, he’s gotten the memo.

Hence the towering irony of the situation.

Carlo Maria Viganò, who’s aspired for more than a decade to be the great Vatican whistleblower – first during his tenure at the government of the Vatican City state about alleged financial irregularities, and later about Francis and McCarrick – actually may have done more than virtually anyone else to ensure that whistles bishops might otherwise be blowing, especially in the U.S., remain silent.