ROME – Although right-wing populist Matteo Salvini is now Italy’s undisputed political leader after his Lega party finished in first place in last week’s European elections, he doesn’t bask in universal acclaim. Among other expressions of disapproval, some Italians who reject his anti-immigrant, anti-outsider rhetoric have taken to showing up at his rallies and other events dressed as Zorro, the legendary swordfighter.

Thus it was that the Italian newsmagazine L’Espresso, attempting to capture the obvious tension between Salvini’s vision and that of Italy’s other undisputed point of reference, Pope Francis, put an image of the Argentinian pontiff in a Zorro costume on the cover of last week’s issue.

(The headline was Zorro subito!, a play on the famous chant at the funeral Mass of Pope John Paul II, Santo subito!, meaning “Sainthood now!”)

The cover story was introduced by an essay from Marco Damilano, the editor of L’Espresso and a veteran Italian journalist who got his start working on a news magazine published by the Italian bishops. (It was eventually suppressed, by the way, amid charges of censorship in the era of Cardinal Camilo Ruini, the ultra-powerful Vicar of Rome and president of the Italian bishops’ conference under St. John Paul II.)

To begin with, Damilano made the interesting observation that many of today’s nationalist populist movements in Europe appear to have their greatest strength in territories of the former Habsburg Empire: Hungary, parts of Poland, and northern Italy, the former Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia, which today forms the base of Salvini’s Lega party, formerly the “Northern League.”

Of course, that leaves France and the UK out of the equation, where populist movements also finished first in the European elections, but the overlap with Habsburg lands is nevertheless striking. At one level, it’s entirely understandable, given that defending the Catholic-Christian identity of Europe was part of the empire’s rhetoric and ideology.

Still, the Habsburgs also had a reputation for handling what was then known as Europe’s “nationalities” problem more successfully than most, allowing their territories significant self-government and turning the senior ranks of both the military and the civil service into a genuine melting pot.

It’s ironic, therefore, that the 21st century version of the “nationalities” problem is especially acute in the same place which, not so long ago, was considered an exemplar of enlightenment.

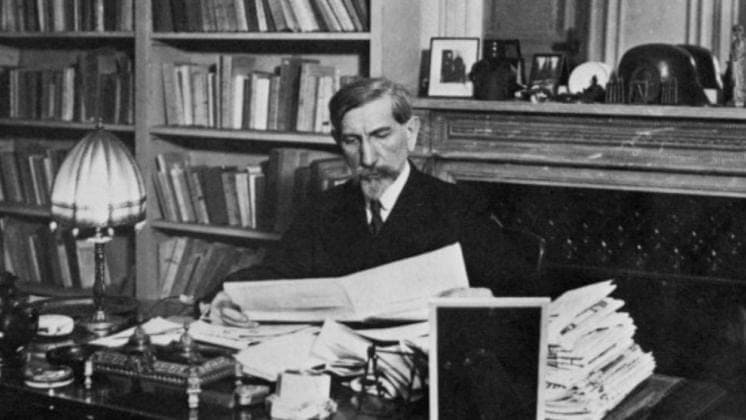

More provocative still, however, was Damilano’s comparison between Salvini and Charles Maurras, a 19th century philosopher, poet and political activist who was the intellectual architect of Action française, a royalist and nationalist movement extolling integralism and Catholicism as alternatives to what they regarded as an unstable and unreliable parliamentary democracy.

Maurras himself was a non-believer, but he saw traditional Catholicism as a force of order in French society, especially in the wake of the revolution. As Damilano put it, Maurras had little use for the Christianity of the Gospels, which he regarded as anarchic, preferring the Church that resulted from the Edict of Milan and its close alliance between throne and altar.

(No one, by the way, is suggesting that Salvini has quite so erudite a conception of the Lega, although he too is given to invoking the symbols and heroes of Catholicism to make his points, often brandishing a rosary at his rallies and even in his post-election press conference on the evening of May 26.)

Despite the fact that Action française promoted Catholicism and that most of its members, including a significant swath of the French clergy, were Catholic, it ran afoul of ecclesiastical authority.

Watching things unfold from Rome, Pope Pius XI became concerned about Maurras’s unorthodox conception of Christianity and especially the influence that Action française was exercising over French Catholic youth. In December 1926 Pius XI issued an official condemnation of the group, and several of Maurras’s writings were placed on the Vatican’s index of forbidden books.

Famously, those moves did not go down well with the French Jesuit Cardinal Louis Billot, who believed that Rome should support the monarchist and nationalist currents in the country. He protested vigorously, leading to a September 1927 meeting with Pius XI in which he submitted his resignation as a cardinal, becoming the only Prince of the Church in the 20th century to lose that status.

The papal crackdown significantly diminished the following of Action française, though it managed to keep going at a reduced level and is still in existence today following several reformations and transformations. However, it was denied any possibility of suggesting Church support for its activities and ideas.

That background suggests the following food for thought: In standing up to today’s right-wing, nationalist and populist movements in Europe, Francis isn’t simply indulging a personal whim but building on what’s been a consistent papal policy since Pius XI – who was also the pope who decided to end the “Roman Question” with the 1929 Lateran Pacts, essentially signaling that the Vatican had made its peace with the separation of Church and state.

(As a footnote, though he’s hardly there yet, German Cardinal Gerhard Müller, former head of the Vatican’s doctrinal agency, could be on his way to becoming the Billot of the Salvini era. In the wake of the elections, he publicly counseled the pope and his team to pipe down and make nice in an interview with Italy’s daily paper of record, Corriere della Sera: “A Church authority cannot speak in such an amateur way about theological questions and especially it must not intrude in politics, when there is a democratically legitimized parliament and government as there is in Italy,” Müller said.)

Whenever Francis is seen as challenging Europe’s populist tide with his open support for migrants and refugees, it’s often framed as a maverick Third World pope once again breaking the mold and leading the Church into a new era.

What history may actually suggest, however, is that the perceived antagonism between the Matteo Salvinis of the world and the Catholic forces mobilized by Francis is that this is indeed an expression of a new era – but one launched long before Francis got here, which has become more or less standard operating procedure for popes regardless of their provenance.

Follow John Allen on Twitter: @JohnLAllenJr

Crux is dedicated to smart, wired and independent reporting on the Vatican and worldwide Catholic Church. That kind of reporting doesn’t come cheap, and we need your support. You can help Crux by giving a small amount monthly, or with a one time gift. Please remember, Crux is a for-profit organization, so contributions are not tax-deductible.