ROME – It’s an over-used metaphor, but right now ecclesiastical Rome has the feel of Super Bowl week. There’s a consistory for the creation of new cardinals today, the opening of the much-anticipated Synod of Bishops on the Amazon Sunday, and the canonization of John Henry Newman one week later — not to mention a welter of counter-synods and protests among Pope Francis’s most determined critics.

Herewith, a sampling of sights and sounds from an extraordinary Roman period. I’ll be providing a daily digest as the month rolls on.

New Cardinals

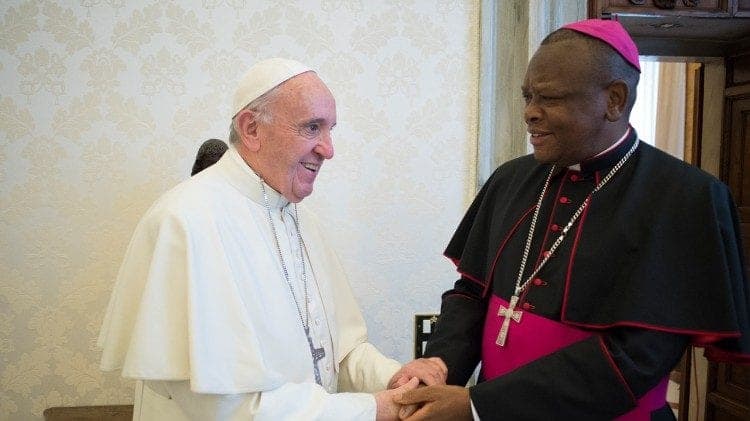

The Vatican has been making several of the new cardinals in today’s consistory available to the press over the last couple of days, which gave me the opportunity Friday to spend some time with three new Princes of the Church: Sigitas Tamkevicius of Lithuania, Jean-Claude Hollerich of Luxembourg and Fridolin Ambongo Besungu of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Each man was impressive in his own way.

Hollerich, for example, is a remarkably gifted polyglot, serving up fluent answers to questions from reporters in French, English, Italian and even Japanese, reflecting his twenty years in Japan teaching at the Jesuit-founded Sophia University.

Only 61 years old, Hollerich also revealed himself to have a lively sense of humor. I noted that he’s one of three Jesuits in this consistory out of 13 total new red hats, and asked how he sees the Jesuit influence on Pope Francis.

“Very small, to tell you the truth,” he laughed.

“I rather see the influence of this pope on the Jesuits,” he said. “The Jesuits are a bunch of people who are very committed to Christ, but also very individualistic from time to time. I think this pope is succeeding at bringing the Jesuits back to their first mission, which is to serve the Church.”

Considered one of Francis’s most reliable allies among the European bishops, Hollerich was ready to pounce with a very “Franciscan” reply when asked what’s the biggest change now that he’s a cardinal.

“The first thing I have to change is myself,” he said.

“When you listen to the teaching of the pope, he calls us to a personal conversion, and that’s as true for cardinals and bishops as for lay women and men,” Hollerich said. “We have to undergo a conversion to Christ in order that our proclamation of the Gospel can be really heard by people.”

He joked that despite the Gospel story of the shepherd who leaves 99 sheep behind in order to go after the one who’s lost, in contemporary Europe it’s more there are 99 lost sheep and only one who’s still in the church.

“We have to go see which pastures these people are on,” Hollerich said. “What’s attracting them? Where do they see life? Every human being is striving for happiness, for meaning, in their lives, so we have to find people where they are.”

In the case of Tamkevicius, who’s over 80 and therefore among the “honorary” cardinals who can’t vote in the next conclave, it’s his personal story that’s most inspiring. He spent almost a decade in Soviet forced labor camps, not only because he was a Catholic priest but because of his unyielding defense of human rights.

Tamkevicius said Friday that what sustained him during those years in prison was prayer, especially saying Mass, which he had to do in secret because religious expressions were officially prohibited. How much the Mass meant can be glimpsed from his attitude to the kinds of work his jailers forced him to do, telling us he had various jobs at one time or another – cook, iron worker, dishwasher, and several others.

When I jokingly asked his favorite, his response was telling: “I liked washing dishes best, because there in the kitchen it was fairly easy to sneak away and say Mass.”

As footnote, I was curious as to how Tamkevicius managed to find wine for the liturgy. He explained that in the camps they would give prisoners a meal ticket, and generally in their food he’d find both bread and dried grapes. He’d pocket some of both, using the grapes to make a crude wine.

Obviously, giving the red hat to such a man is a way for Francis to honor both his personal suffering and that of the church he represents. Tamkevicius, however, was matter-of-fact about his own sacrifice.

“If a believer isn’t ready to suffer for his faith,” he said simply, “then he’s not much of a believer.”

Of the three new cardinals Friday, I confess I was most looking forward to meeting Ambongo, since he’s a Capuchin and I was educated by the order out on the high plains of Western Kansas. He becomes the second Capuchin cardinal in the world, after Sean O’Malley of Boston – though unlike O’Malley, he wears around clerical blacks rather than the trademark Capuchin brown robe.

In Congo, where the Catholic Church is the most trusted force in civil society, ecclesiastics also have to be skilled politicians. As Ambongo put it, “The Church is the one voice and one hope of our people.”

As proof of the point, his predecessor as the Archbishop of Kinshasa, Cardinal Laurent Monsengwo, was briefly the de facto head of state in the 1990s after the death of Mobutu Sese Seko, in a moment when the country was making a transition from authoritarianism to something approaching democracy. Monsengwo not only served as president of a transitional “High Council of the Republic,” but also as transitional speaker of the national parliament in 1994.

Ambongo certainly seems to have a knack for politics, especially the fine art of deflection. For example, asked a question about the viri probati, or married priests, a topic expected to come up in the Amazon synod, he launched into a soliloquy about the Amazon as the lung of the world and how many of the issues of deforestation and exploitation it faces also apply to the Congo Basin.

It was rousing, even if utterly unrelated to what he’d actually been asked.

That’s not to say, however, Ambongo is afraid of taking a stand. Far from it – like Tamkevicius he also did time in jail, in his case under President Laurent-Désiré Kabila at a time when Ambongo was the chair of a church-sponsored Justice and Peace Commission, denouncing corruption and human rights abuses.

The 59-year-old Ambongo spoke movingly of what it means to be a pastor in a place like Congo, ranked by the UN as the second-poorest country in the world.

He described, for instance, traveling by helicopter to visit one of the epicenters of the 2018 Ebola outbreak that had been abandoned by virtually everyone else, including the state. Upon arriving he discovered that the local pastor was himself infected, so Ambongo got as close to him as health workers would allow and then prayed over him. In the end, the priest recovered.

“Some people said it was a miracle,” Ambongo said, “but to me the miracle was that the Church never deserted the people … we’ve always stayed close, no matter what.”

Ambongo also spoke of how his vocation was born in a sense of admiration for a Belgian Catholic missionary who’d come to work in his part of the Congo. Watching him move heaven and earth to help his people, Ambongo said, he was inspired to join the Capuchins to try to be like that priest.

I asked if the fact of being a Capuchin has had an influence on his style of being a bishop.

“Without a doubt,” he said. “If I’m the kind of pastor I am today, that everyone knows, it’s because of my Capuchin formation. Everything I do today … the struggle for justice, for peace, for human dignity, these are things that have come to me from my formation as a Capuchin.”

Ambongo said he believes that despite being a Jesuit, the current pope is leading the Church in the style of St. Francis – “which means we’ll get along,” he quipped.

It remains to be seen what these new Princes of the Church may do with their newfound, exalted status, and what impact it may have either on the Church or their parts of the world. Based on Friday’s exchanges, however, it would seem that whatever they do, it will be interesting to watch.

Follow John Allen on Twitter: @JohnLAllenJr

Crux is dedicated to smart, wired and independent reporting on the Vatican and worldwide Catholic Church. That kind of reporting doesn’t come cheap, and we need your support. You can help Crux by giving a small amount monthly, or with a onetime gift. Please remember, Crux is a for-profit organization, so contributions are not tax-deductible.