ROME – Famously, the United States and Iran haven’t had diplomatic relations since they were cut off in 1980 amid the hostage crisis. Officially the two countries communicate through the Swiss embassy in Tehran, and Swiss officials were dutifully summoned Friday to hear Iran’s protest of the killing of General Qasem Soleimani, describing it as a “blatant example of American state terrorism.”

In all honesty, the U.S. probably didn’t need a diplomatic communique from the Swiss to grasp that the Iranians were upset, since it already had been made abundantly clear through pretty much every media outlet on the planet.

Given that Washington and Tehran are unlikely to restore direct ties right now, and that communication between the two sides is nonetheless essential if a regional conflagration is to be prevented, the question arises as to which player on the global stage is best positioned to broker a dialogue that might allow cooler heads to prevail.

As counterintuitive as it may seem, there’s a case to be made that the Vatican might be a good choice.

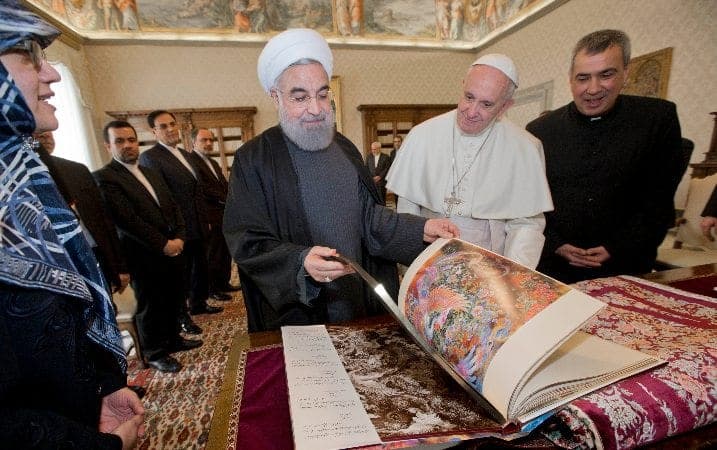

To begin with, the Vatican’s diplomatic relationship with Iran dates to 1954, a full three decades before formal ties with the U.S. were launched under President Ronald Reagan in 1984. Post-revolutionary Iranian leaders have been especially anxious to trumpet their entrée in the Vatican, as a way of counteracting Washington’s efforts to depict Iran as a pariah state. Iran currently has more diplomats accredited to the Vatican than any country in the world other than the Dominican Republic, which is a clear sign of how seriously they take the relationship.

Of late, Iran has been appreciative of the Vatican’s line on Syria, which is not premised on regime change by removing President Bashar al-Assad from power. Further, the Vatican sees Iran as key to any solution in Syria, including stronger protections for Syria’s Christian minority, and so treats the country and its leaders with a deference they often don’t get from other Western institutions.

In addition, the Vatican is generally opposed to economic sanctions as a form of political leverage, fearing their consequences fall mostly on innocent civilians. That’s why the Vatican always has opposed the U.S. embargo on Cuba, for example, and why, on the same principle, it’s never endorsed U.S.-backed sanctions on Iran over violations of various nuclear accords or other disputes.

Ironically enough, the Vatican under Pope Francis might actually have a harder time being seen as a fair broker by Washington than Tehran, given the way Francis and his team have made clear their distaste for the sort of American religious conservatives who make up an important chunk of President Donald Trump’s electoral base.

On the other hand, there are a number of U.S. Catholic leaders with influence in the Trump administration. In any event, given that Islamic societies historically have seen the Vatican as the chaplain of the West, the impression that Francis isn’t in the bag for the White House could actually be an asset in this situation.

Finally, there’s an underlying reason why the Vatican can engage Tehran in a way that the Swiss or other diplomatic players simply can’t, and it can be expressed in one word: God.

At the leadership level, Iran is a theocracy, and even if it’s certainly adept at hard-nosed realpolitik, the thought world of its leadership class is nevertheless suffused with religious concepts and vocabulary. The Vatican is the lone serious global player that can engage Iran at that level and be taken seriously.

It’s a special advantage given that, as I’ve observed before, Catholicism and the Shi’a strain of Islam that dominates Iran enjoy a natural kinship. Unlike Sunni Islam, which is sort of the Protestant analogue in the Muslim world, the Shi’ites are led by a clerical caste, they acknowledge both scripture and tradition as sources of revelation, they have a strong theology of sacrifice and atonement, and they also feature an important current of popular religion expressed in feasts, devotions and even the equivalent of saints.

Those parallels give the Vatican natural points of entry in forging relationships with Iranians that no other diplomatic player could possibly wield.

What might a papal initiative in this moment of crisis look like?

To begin, Francis could write personally to both Trump and Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, much like the letters Francis dispatched in 2014 to Cuban leader Raul Castro and then-U.S. President Barack Obama that helped pave the way for restoring diplomatic relations between Havana and Washington.

In his letters, Francis could offer the Vatican’s services as an intermediary between Iran and the U.S., or, at the very least, as a backchannel means of communication between the two nations to ensure that potentially momentous military decisions aren’t made on the basis of miscalculations or incomplete information.

In terms of something more dramatic, Francis could steal a page from St. John Paul II’s playbook and dispatch personal emissaries to both Tehran and Washington, urging them to show restraint, just as the Polish pope did with Baghdad and Washington in 2003 in an effort to prevent war in Iraq. Obviously that effort failed, but the fact it didn’t work once doesn’t mean it never will.

Even bolder, Francis could announce his intention to visit the Middle East, with the idea being to convene Iranian and U.S. officials along with other regional players in an effort to promote dialogue and peaceful solutions. One option for a venue would be Lebanon, a country Francis promised to visit as far back as 2017, which has close ties to Iran but also a decent working relationship with the U.S. Lebanon also features one of the largest Catholic populations in the Middle East, making it a natural for a papal foray.

Whatever pathway seems most promising, there would seem to be a moment right now in which creative papal leadership could be crucial. It may not be the start to 2020 Francis quite envisioned, but for better or worse, it’s the hand he’s been dealt.

Follow John Allen on Twitter: @JohnLAllenJr

Crux is dedicated to smart, wired and independent reporting on the Vatican and worldwide Catholic Church. That kind of reporting doesn’t come cheap, and we need your support. You can help Crux by giving a small amount monthly, or with a onetime gift. Please remember, Crux is a for-profit organization, so contributions are not tax-deductible.