ROME – To paraphrase Ronald Reagan, here I go again: I’m going to outline again why the Capuchin Franciscans are my favorite religious order in the Catholic Church. I know I return to this subject with some regularity, but they just keep being cool.

The origins of my affection are biographical: I was educated and formed in the faith by Capuchins on the high plains of Western Kansas, and you’ll never need any further proof of their sanctity than that they put up with me as a precious (okay, that’s a polite word for “insufferable”) young man.

However, even if I’d never known the Capuchins personally, I like to think I’d still have gravitated into their orbit. In terms of why, look no further than an Italian Capuchin named Cesare Bonizzi, better known to the public as “Brother Metal.”

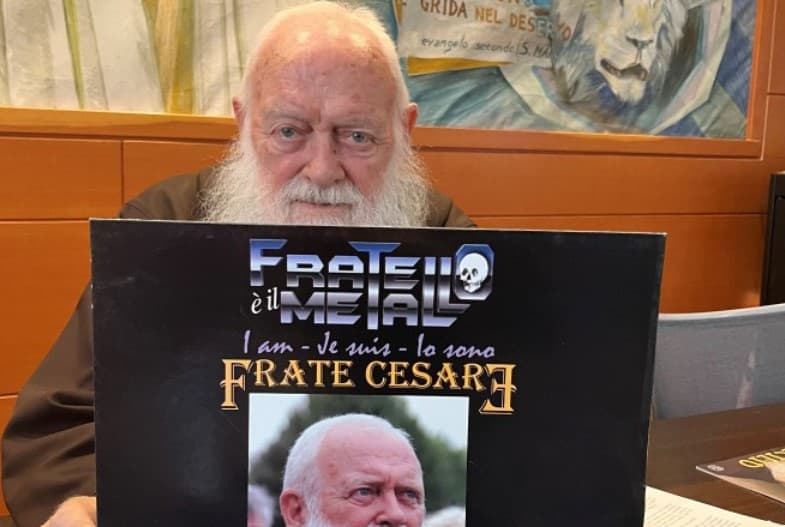

In the 1990s and 2000s, Bonizzi released a series of heavy metal albums under the name of Fratello Metallo, or “Brother Metal,” though he meant that moniker not as a reference to himself but to the musical genre, considering it a brother to the faith.

Here’s an example of the kind of tracks he produced.

As Bonizzi once said, “Metal is the most energetic, vital, deep and true musical language that I know.”

He came to that realization, by the way, after attending a Metallica concert in 1990 in Milan. He said a friend who was working concessions that night invited him, and so he showed up in his Capuchin habit and was immediately swarmed by a crowd of metal-heads who demanded to know what he was doing there.

“I started having contacts with these young people,” he said. “I was able to talk about Jesus, I told them life is marvelous, and that alcohol is dangerous … I’ve always understood evangelization as something of the street, of the people. It was only later that I started using metal as a style.”

Among other things, Bonizzi, now 77 years old, went to become a friend and sort-of spiritual guide to Dave Mustaine, a former guitarist for Metallica who later founded Megadeath.

In all, Bonizzi would release 25 albums containing 365 songs, or one for every day of the year, before quitting in 2009 after a controversy erupted over an album cover in which he was shown with a rosary in one hand and making what’s widely considered a satanic gesture with the other (though he always insisted he meant it as a symbol of the Trinity.)

It’s worth briefly telling the story of how Bonizzi became a Capuchin in the first place.

The youngest of ten children, he started out in life as a salesman for Bulova, the luxury watchmaker. In his spare time, he volunteered with an Italian non-profit called Telefono Amico, which is basically a call-in crisis center. He turned out to have a gift for listening to people in pain, which eventually helped him make a couple of big sales in Siena with two grieving people, one of whom had lost his wife and the other a son.

Bonizzi quit after that, disgusted with himself for profiting off someone else’s loss. A typical young seeker in the early 1970s, he first decided to enter a Hindu ashram in the city of Nice in France. They directed him to a Cistercian monastery near Cannes, where he found the silence “chilling” and promptly left.

Eventually he returned to his home city of Milan, where, in 1975, a priest friend recommended that he get in touch with the Capuchins. He said he showed up the door of a friary with long hair, a baggy sweater, torn jeans, a manta ray necklace and barefoot … and, despite it all, they took him in.

From that point on, he said, “I was finally home.”

Bonizzi joked that his mom couldn’t believe it, since she’d always been frustrated that her children didn’t seem to share her Catholic faith: “Forget about a priest or a nun,” he recalled her saying, “I just wish at least one of them went to Mass!” He also confided that about a month after he’d entered the friary, a friend who knew him from before showed up “to see if I’d run away.”

Forty-eight years later, Bonizzi still hasn’t run away.

In a sense, Bonizzi is a counterpoint to Cristina Scuccia, better known to the Italian public as “Sister Cristina,” who was an Ursuline nun when she won the talent show “The Voice of Italy.” Scuccia since has left religious life to continue singing professionally; Bonizzi, on the other hand, stopped his musical career to remain a religious.

“I’m just what you see,” he said recently. “I’ve never had any doubts … Brother Metal has stopped, Brother Cesare no.”

While Bonizzi confesses he had run-ins with a couple of his Capuchin superiors, in general, he said, his brothers in the order always showed him tremendous support.

That, in a nutshell, is what makes the Capuchins what they are: Solid in the faith and their vocations, and, for precisely that reason, able to tolerate a staggering diversity of expressions of how to bring God to the world.

Rock on, Brother Cesare … and all your Capuchin confreres, who may never lay down a rock-and-roll track in their lives, but who nevertheless know what it means to kiss the sky.