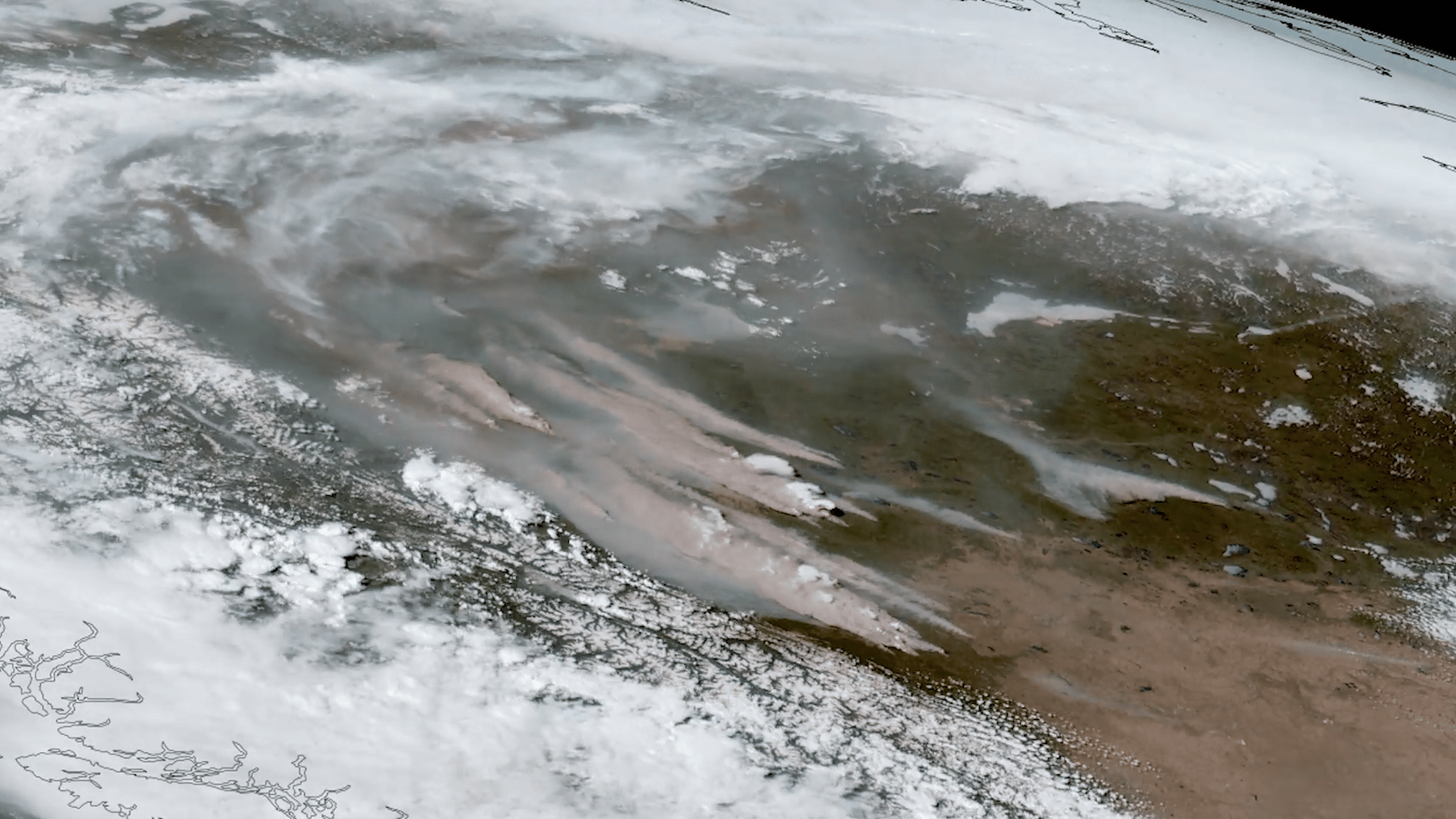

It was hard to breathe in southern New England this past weekend – again – after smoke from the ongoing wildfires in northern Quebec wended their way to us here. There are fires burning all across Canada this summer, in fact, making this already the worst season for them on record.

Early in June, when the smoke first blew down from the great north, it got so bad that one couldn’t see the waters of the Hudson from the George Washington Bridge, let alone New York or Fort Lee in New Jersey on either side of the span.

I heard on the radio as I waited with my family to get out of the municipal beach parking lot on Saturday night after the local fireworks display that the air quality in our neck of the woods was worse than in New York this time. There’s been lots of talk about who and what is to blame for the fires, but we have a confluence of causes contributing to genuinely tough conditions far away from the blaze that is sending particulate into the air.

That got me thinking about the “ecclesiastical air quality index” and how one could measure it, as well as about the dynamics that go into making the air more or less breathable.

For one thing, it is now abundantly clear that everything in the Church is local, and also that nothing in the Church is merely local.

Years of dogged reporting brought to light some very bad doings in Knoxville, Tennessee, to light. Bishop Rick Stika of Knoxville resigned under a cloud of suspicion after an apostolic visitation – that’s a sort of official Vatican-ordered fact-finding mission – but never faced formal charges, even though Stika admitted to interfering with one investigation into a rape allegation against a seminarian who was one of Stika’s favorites, and copious evidence to suggest Stika played very fast and very loose with diocesan finances.

Catholics in Knoxville are glad Stika is gone, but lots of folks are wondering why he got off so easily. They wonder why Pope Francis allowed him to resign with his honor and his pension intact, and frankly it is a legitimate question.

The use of the visitation in lieu of criminal investigation also fits papal modus operandi under Francis, who has built a reputation as a reformer but happens to be fairly reluctant to use the reform laws he made ostensibly to facilitate a major house-cleaning operation. It’s what Francis did in Buffalo, NY, with Bishop Richard Malone.

That Francis has used his reform laws from time to time, as when he investigated Bishop Michael Hoeppner of Crookston, Minnesota, only adds to the perplexity. Francis let Hoeppner resign, too, even after an investigation into whether Hoeppner “had intentionally interfered with or avoided a canonical or civil investigation of an allegation of sexual abuse of a minor as described in Article 1 (§1) (b) of the motu proprio Vos estis lux mundi.”

Hoeppner, by the way, presided over his own farewell “Thanksgiving Mass” in the Crookston cathedral. No statement from either the Vatican or the investigators ever said precisely what the investigation had uncovered, or why Hoeppner was asked to resign, or why he was allowed to resign rather than be deposed. By every appearance, Hoeppner is a bishop in good standing.

There are other, more egregious cases, which have received even less attention from the Vatican.

French cardinal Jean-Pierre Ricard – emeritus of Bordeaux and olim president of the French bishops’ conference – admitted to “reprehensible behavior” toward a 14-year-old girl when he was a simple parish priest more than three decades ago. The Vatican opened an investigation in 2022, as did French police, but the French authorities eventually decided the allegations were statute-barred. The 78-year-old Ricard has promised to withdraw from public ministry, but so far has kept his red hat and his voting rights.

Meanwhile, another U.S. bishop with a small rural diocese and an outsized social media presence, Bishop Joseph Strickland of Tyler, Texas, has also recently had an apostolic visitation. Strickland is a fellow who has not been shy about criticizing Francis.

Some of Strickland’s remarks have been intemperate. He praised a video calling the pope a “diabolically disoriented clown,” for example. Strickland has also said that he rejects “[Francis’s] program of undermining the Deposit of Faith.” In fairness, Strickland did clarify that he believes Francis is the pope.

So, there’s that.

Reports suggest the bishops who conducted the Tyler visitation were rather concerned with Strickland’s administration of the diocese. They reportedly asked about how he gets on with clergy and manages personnel and finances. That’s fair enough, and it’s hardly surprising that a fellow who has talked so much out of turn and so loudly should get a come-uppance.

Still, why him – and why no real process, but only a fact-finding mission conducted under pontifical secret and kept under wraps? Why not say what you’re doing and why you’re doing it?

It’s easy to see why dealing with matters quickly and quietly is tempting. There are legitimate upsides to it. Trials – even canonical trials – are expensive and time-consuming. If a leader can be rid of a bad actor without such expense of time and money, it’s frequently not unreasonable.

Sometimes, however, the interests of justice require that people see it being done. A consistent and vigorous application of Francis’s own reform laws could go some way toward doing just that.

In any case, a fellow who loses his see because of mismanagement or worse, ought not be allowed to resign citing ill health or fatigue or some other reason blameless if not praiseworthy. It isn’t fair or even minimally just, including to officials for whom those are actually the real and only reasons for resigning, but who are now under a cloud of suspicion.

The point is that smoke from these and other ecclesiastical wildfires gets caught in prevailing wind currents and pushed by weather systems, then gets carried to far away places where the plumes turn the air acrid and the sky lurid.

Experts say the threat billowing down from Canada won’t really go away until the wildfires generating the smoke are put out. Perhaps the same point applies to the Church’s situation. If we want to breathe cleaner air, maybe we need to put out our own fires first.

At the very least, bishops from bottom to top could recognize that failure to let justice be seen to be done only adds fuel to the blaze.