ROME – There’s never a dull moment on the Vatican beat in the Pope Francis era, and the past week has offered a classic illustration of that truth, featuring dramatic charges of schism against an archbishop, a startling revelation regarding church/state relations in Italy, and a controversial real estate deal that once again could land the Vatican in hot water.

Each story carries a special wrinkle, well worth unpacking.

Did Parolin clear the U.S. bishops on Viganò?

The week’s biggest headline was the breaking news that Italian Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, the former papal envoy to the U.S. who’s gone on to become Pope Francis’s most vocal — and, frankly, most extreme — critic, has been formally charged with schism by the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith.

A June 11 decree summoned Viganò to face the charges, or to designate an attorney acting on his behalf to do so, on June 20. He didn’t show up, and has just a few more days to respond before he’s found guilty and sentenced to some form of ecclesiastical sanction.

For his part, Viganò called the charge an “honor” and showed absolutely no sign of remorse.

One interesting footnote came in the reaction to all this of Italian Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Vatican’s Secretary of State and among Pope Francis’s closest allies.

“I always appreciated him as a great worker very faithful to the Holy See, in a certain sense also an example,” Parolin said of Viganò, referring to a period earlier in his career before he began attacking the pope. “When he was apostolic nuncio he worked extremely well, I don’t know what happened.”

Here’s why that’s such an interesting comment, from a figure who can hardly be suspected of disloyalty to Francis or sympathy for Viganò’s criticism.

When Viganò initially came forward in 2018 to charge Francis with a cover-up in the case of Theodore McCarrick, a number of U.S. bishops were asked for their reaction, and several offered some version of the sentiment that his accusation should be taken seriously. Ever since, that’s stained those bishops with the impression of sympathy for Viganò, a perception that’s become steadily more poisonous with every step Viganò has taken into the black helicopter world of conspiracy theories and paranoia.

Parolin, however, has offered a reminder that perceptions of Viganò in 2018 were different than today.

Back then, most US bishops simply recalled him as a former Vatican official and a reasonably effective ambassador to the States. They had no way of knowing what he would later become, nor were many of them eager in the immediate wake of the McCarrick revelations to be seen as dismissing any accusation, no matter whom it involved.

In other words, hindsight is always 20/20. No doubt, many of those U.S. bishops today would be far more circumspect in their reactions to whatever Viganò has to say. Yet Parolin has highlighted the difference between then and now, a favor (however inadvertent) for which many U.S. prelates probably ought to drop him a thank-you note.

The Past as Prologue in Italian Politics

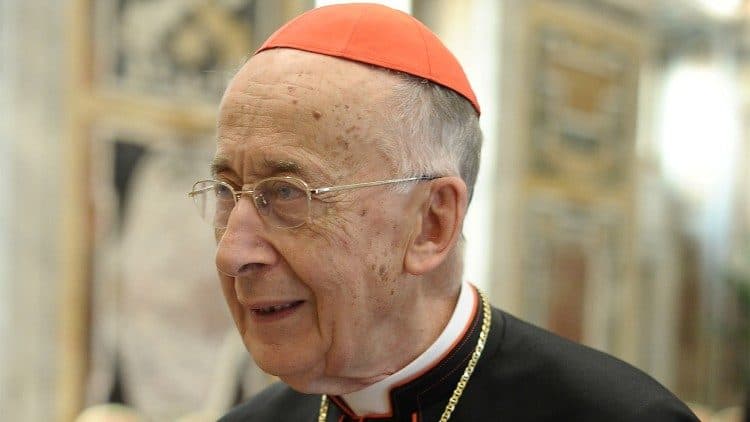

Also this past week, 93-year-old Italian Cardinal Camillo Ruini, who served as the Vicar of Rome and president of the Italian bishops’ conference under St. John Paul II, gave an interview to the newspaper Corriere della Sera looking back over key moments in his career.

Because John Paul II had a strong international agenda, focused early on the confrontation with Soviet communism and later on the globalized world taking shape in the 1990s and early 2000s, he largely left Ruini to run the show in Italy. Arguably, few churchmen of the 20th century enjoyed as much political and power in his own country as Ruini at his peak.

In the new interview, Ruini confirms a report that first surfaced in 2022 concerning a 1994 lunch that took place at Rome’s Quirinale Palace, the residence of the Italian president, hosted by then-President Oscar Luigi Scalfaro for Ruini, who was joined by Cardinal Angelo Sodano, the Vatican’s Secretary of State, and then-Archbishop Jean Louis Tauran, effectively the Vatican’s foreign minister.

Scalfaro, who died in 2012, was a leftist and a believer with a background in the anti-fascist wing of Catholic Action as a young man. During the course of the lunch, according to Ruini, Scalfaro asked for the Church’s help in bringing down the government of then-Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, on the grounds that the media tycoon and political populist was a threat to democracy.

According to Ruini, the three churchmen received the proposal with an embarrassed silence and quietly let it drop.

“I think Berlusconi clearly showed both his strengths and his limits, but he wasn’t subversive,” Ruini said. “If anything, the dangers for the Republic lay elsewhere.”

What makes all this especially relevant is that the stars might be aligning for a similar offer today, with a potentially different outcome.

Once again, the President of Italy, Sergio Mattarella, is a leftist with a background in Italian social Catholicism. Once again, the country’s Prime Minister is a conservative, Giorgia Meloni, whose critics describe her as a threat to democracy, in part for her background in post-fascist parties and in part for a pair of controversial constitutional reforms.

Once again, too, the president of the Italian bishops conference is a powerful churchman and key papal ally, Cardinal Matteo Zuppi of Bologna, who theoretically could summon the political bandwidth to tip things in one direction or another.

The major difference is that while Ruini in 1994 was inclined to give fellow conservative Berlusconi the benefit of the doubt, the more progressive Zuppi is clearly no friend of the Meloni government. Recently, asked a for a reaction to passage of hotly debated constitutional reform providing greater regional autonomy, Zuppi acidly complained that a warning from the bishops about national unity had been ignored.

“It is clear that they did not take us seriously,” he groused.

Can one imagine a scenario in which Mattarella might sound out Zuppi over a possible course change in Italian politics?

Well, let’s just say it’s not completely implausible – and neither is the prospect that this time, a cardinal might be more inclined to consider the possibility.

Two Notes on St. John Paul II

Speaking of Ruini, today Corriere della Sera published another lengthy interview, this one mostly focused on the afterlife — a natural enough concern for a 93-year-old who’s confined to a wheelchair and who needs help even with simple tasks, such as getting a book down off a shelf.

Two notes regarding John Paul II are especially interesting.

First, Ruini says that at one point, John Paul had used a phrase which led people to believe he was endorsing the celebrated idea of theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar that it’s legitimate for a Christian to hope that hell is empty. According to Ruini, he was later told by then-Archbishop Giovanni Battista Re, the pope’s chief of staff, that John Paul had called him in to say that he didn’t want anyone in the Roman Curia attributing that sentiment to him, since he believed that hell not only exists but that it’s populated.

Second, Ruini complains at another point about theology adopting ideas incompatible with the Christian faith. Pressed for an example, he cited the notion that Christ is not the only path to salvation, one often adopted by theologians attempting to promote inter-faith dialogue.

Ruini noted that in 2000, the then-Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith under Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI, issued a document called Dominus Iesus reaffirming Christ as the lone savior of the world. At the time, Ruini said, it was controversial, and some people tried to claim it represented Ratzinger’s thinking more than John Paul’s. In fact, however, Ruini said John Paul had personally requested the document, and upon reading it declared that it should end all the “quibbles.”

Alas, Ruini conceded, the very next day the quibbles resumed.

For those who read Italian, the full text of the Ruini interview is here.

Once More into the Breach on Land Deals

The last time the Vatican got involved in a complicated real estate deal involving millions of dollars, it didn’t end especially well.

An aborted purchase of a former Harrod’s warehouse in London, originally slated to be converted into luxury apartments, triggered the “trial of the century” that ended in the conviction of nine defendants, including Cardinal Angelo Becciu, for various forms of embezzlement and fraud.

Now the Vatican appears to be heading once more into the real estate breach, negotiating the acquisition of a shuttered Roman hospital as the new headquarters of the papally sponsored Bambino Gesù pediatric clinic.

The deal was announced in mid-February, and new details emerged this week in a report by the online news site RomaToday.

The facility in question is the sprawling Forlanini Hospital in Rome, built in the 1920s and 30s as the world’s first major facility devoted entirely to the treatment of tuberculosis, which over time evolved into a general service hospital until it was closed in 2015 amid disrepair and ballooning deficits.

The 70-acre campus, which at its peak has more than 4,000 bed spaces for patients, originally was slated to be remodeled and returned to use as a public facility. Those plans, however, were never realized, and in February a signing ceremony was staged in which a deal was inked to turn over at least part of the facility to the Vatican to allow the Bambino Gesù to expand, something described as impossible as its current location.

Under the agreement, the Vatican is supposed to buy a dilapidated building and its grounds from the Lazio Region, which owns the property, “at a price to be established” – reportedly around $70 million – and then construction of a new hospital would be paid for by Italy’s workplace accident insurance agency INAIL. In turn, INAIL would then rent the new facility to the Vatican, which would be considered extra-territorial Vatican property under the terms of the 1929 Lateran Pacts.

Much about the financing remains mysterious, including the role of the Italian version of a workers’ compensation program in a hospital building project. It’s also not clear how the reported sale price was established, since estimates for the value of the property are said to range between $450 and $600 million.

It remains to be seen if anybody will be charged with crimes when the dust settles, but for now it’s clear the deal isn’t playing to universally positive reviews. An Italian citizens’ group, among others, is leading protests claiming that a facility which is supposed to be for public use is being sold off on the cheap to the Vatican.

In part, those complaints reflect the fact that the deal was signed on the Vatican side by Italian Cardinal Pietro Parolin, the Secretary of State, while representing the Italian government was cabinet secretary Alfredo Mantovano – who also happens to be a lifelong Catholic and the former president from 2015 to 2022 of the Italian branch of the papal foundation Aid to the Church in Need.

The suggestion, therefore, is that Mantovano has delivered a sweetheart deal to his ecclesiastical buddies at the expense of the public interest.

No timetable has been announced in terms of when the move by Bambino Gesù will be complete, and much may yet depend on how public reaction plays out. One would assume that, post-London, sensitivities in the Vatican to the possible ramifications of real estate deals are also higher.