My first encounters with Elie Wiesel came during several early conferences on the Holocaust where he was a plenary speaker. I was amazed at the way he could silence a large ballroom with his message. It clearly had profound intellectual content, but most of all, it spoke to the heart.

Without the latter, the passionate commitment to remembrance and continuing human dignity that were the hallmark of Wiesel’s contribution to contemporary global society likely would have fallen on deaf years.

My encounters with Wiesel took on much greater depth when he graciously included me in the original membership of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council, which was charged by President Jimmy Carter, with the unanimous consent of Congress, to erect a suitable memorial to the victims of the Nazi genocide in the nation’s capital.

This presidential appointment allowed me to participate in one of the most meaningful events of my life, as I worked with Elie and many other committed Jews and non-Jews in transforming Carter’s mandate into concrete reality.

During the years of work with Wiesel on the design and construction of the museum, I gained many insights from him as he worked through the often difficult process of deciding on what should be and not be included in a memorial museum located on some of the most sacred space in Washington.

Many of those insights have remained ingrained in my consciousness to this day.

On occasion, Wiesel would speak of the necessity of madness. For him, madness was not insanity. It was rather the willingness, often in the face of incredible odds, to stand up for human dignity no matter what one’s national identity, racial heritage or sexual orientation might be.

Early on in the process of building the museum, a wealthy benefactor offered to contribute the first substantial gift to the museum. But the offer had a condition attached. The donation depended on Wiesel agreeing that only Jewish victims of the Nazis would be memoralized in the museum.

The gift was tempting, because the U.S. Congress was pressing the Holocaust Council to get started on the museum, and its funding had to come largely from the private sector. Yet in the end, Wiesel declined the offer.

From there on in, he remained committed to memorializing all the Nazi victims, meaning the disabled, the Poles, gay people and Roma and Sinti (Gypsies). While Wiesel certainly recognized the special features of the Nazi onslaught against the Jews, he was committed to the principle that one can never prioritize victimization.

And so, the inclusion of all the victims in the museum’s permanent exhibits was settled.

One of the most trying moments in my relationship with Wiesel came on the occasion of President Ronald Reagan’s decision to visit the German military cemetery at Bitburg. Wiesel was deeply disturbed at the president’s choice, and publicly criticized it. He summoned a number of the members of the council to an emergency meeting in his office, myself included.

He expressed serious reservations about remaining the chair of the council. Resignation seemed the only way to protect his own integrity and that of the victims. After profound soul-searching with those of us in the meeting, he decided continuing his commitment to the erection of the museum had to take priority over his profound regret that Reagan’s visit had compromised the moral challenge that the Holocaust continues to place before humanity.

For me, these several hours in the room with Wiesel showed the depth of his own moral commitment and demonstrated how moral decision-making might emerge in very difficult circumstances.

Wiesel also showed great foresight in agreeing with a notion originally proposed by the late Hyman Bookbinder of the American Jewish Committee, a longtime social activist and a member of Carter’s original exploratory commission on the Holocaust, which eventually recommended the creation of the permanent council.

Bookbinder insisted that a future museum should not focus exclusively on memorializing the Nazi victims. It also had to include a futuristic dimension. Wiesel took up this idea, and made it a central part of the museum’s motto — “Remembering for the Future”.

He clearly saw the need for the museum to include programming with regard to any subsequent genocides through the creation of a Committee on Conscience. Though it took some time for this committee to see the light of day, because of political opposition and concern on the part of some survivors, Wiesel held firm to his support.

Today the museum is a major force in Washington on the issue of genocide, thanks to Wiesel’s persistence.

Finally, I cannot help but think about one of Wiesel’s most notable quotes as we today struggle to see our way through a time of continuing terror. Wiesel said that if we forget the victims of the Nazis, in effect we kill them a second time.

As I listened to the news about the terror attack at the Istanbul airport, this quote haunted me as the news media reported on how quickly the airport was reopened (the Turkish Airlines flight from Chicago to Istanbul was delayed only about fifteen minutes). I can certainly understand the desire on the part of the Turkish authorities to prevent the terrorists from any ongoing victory.

But Wiesel’s powerful comment must also challenge us against accepting such a situation as the “new normal”, as one U.S. government official put it. We must continue to mourn the victims of genocide and terror attacks, as well as the killing of so many in our urban areas. Otherwise such human destruction can easily become the “new normal.”

The final chapter of Elie Wiesel’s legacy has been closed by his death. But the passion of his vision for human dignity and the continuing challenge of his personal moral commitment grounded in his personal experience of victimization will live on. For me, they remain seared in the depths of my soul.

For this, I am grateful that our lives intersected.

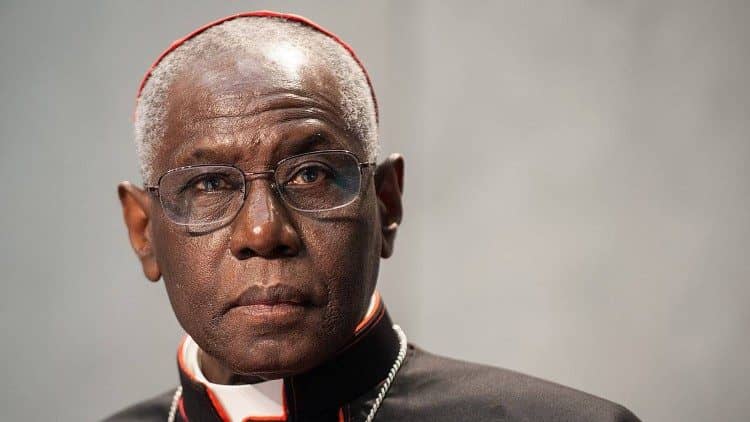

Father John T. Pawlikowski OSM, Ph.D., is Professor of Social Ethics and Director of the Catholic-Jewish Studies Program at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago. He served for four terms on the board of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and continues as a member of its Academic Committee and its Committee on Religion, Ethics, and the Holocaust.