Each day between now and the May 7 conclave to elect a successor to Pope Francis, John Allen is offering a profile of a different papabile, the Italian term for a man who could be pope. There’s no scientific way to identity these contenders; it’s mostly a matter of weighing reputations, positions held and influence wielded over the years. There’s also certainly no guarantee one of these candidates will emerge wearing white; as an old bit of Roman wisdom has it, “He who enters a conclave as a pope exits as a cardinal.” These are, however, the leading names drawing buzz in Rome right now, at least ensuring they will get a look. Knowing who these men are also suggests issues and qualities other cardinals see as desirable heading into the election.

ROME – In the classic 1941 noir film, a cultured criminal named Kasper Gutman says to the rough-around-the-edges detective Sam Spade, “By gad, sir, you are a character! There’s never any telling what you’ll say or do next, except that it’s bound to be something astonishing.”

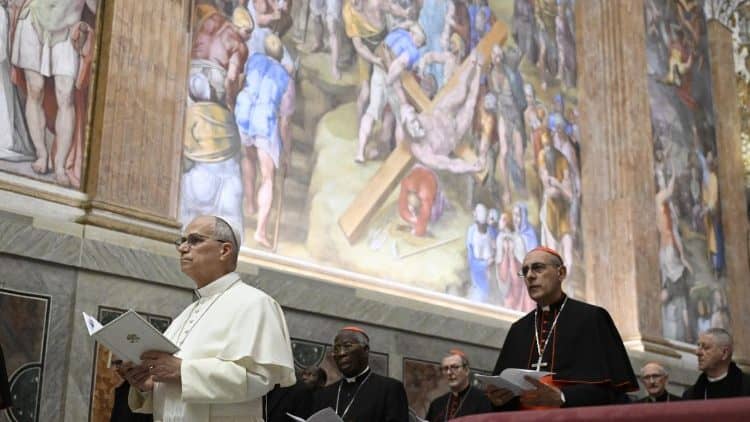

That bit of dialogue, of course, comes from the John Huston classic “Maltese Falcon,” but it might well also be said of the great Maltese contender in the 2025 conclave, 68-year-old Cardinal Mario Grech.

During his run as the Bishop of Gozo in Malta from 2005 to 2019, Grech generally was considered a conservative, seen as standing to the right of, and sometimes at odds with, Archbishop Charles Scicluna, who heads the Archdiocese of Malta.

That reputation, however, dissolved like sugar in hot coffee once Grech was appointed Secretary General of the Synod of Bishops by Pope Francis, a role in which he became a champion of the late pontiff’s vision for a more “synodal” church and of the progressive reform causes with which the synod came to be associated.

You thus never quite know what you might get from Grech, but it is often something astonishing.

Born in Gozo in 1957, the young Grech attended a grade school run by the Carmelite sisters and then entered the diocesan seminary of Gozo. He was ordained to the priesthood in 1984 and shipped off to Rome for further studies at the Pontifical Lateran University, were, among other things, he learned Italian. He later earned a doctoral degree in canon law from the University of St. Thomas, the “Angelicum,” and worked for the Roman Rota, the Vatican’s main working court, which mostly handles marriage cases.

After a period back in Malta as a priest, much of its spent working on church tribunals, Grech was named the Bishop of Gozo by Pope Benedict XVI in November 2005. He launched an ambitious diocesan mission, including visiting Maltese diaspora communities in various parts of the world; created a number of commissions and other initiatives, including a diocesan commission for the protection of children and vulnerable adults from sexual abuse; and served as the representative of the Maltese bishops both to the European bishops’ conference and the Italian bishops’ conference.

In April 2010, Grech hosted Pope Benedict during a brief two-day visit to Malta to mark the 1,950th anniversary of St. Paul’s famous shipwreck on the island.

When a debate broke out in 2011 over the legalization of divorce in Malta, Grech came out in opposition in tandem with the island’s clergy, warning that voters would be “accountable to Jesus.” (A referendum allowing divorce passed with 53 percent of the vote.)

He also became an outspoken defender of migrants during Malta’s migrant and refugee crisis, accusing elements of Maltese society pushing for a policy of closure of “racism.” At one point, he criticized Italian politician Matteo Salvini, leader of the far-right Lega party, for brandishing a rosary while engaging in anti-immigrant tirades during campaign rallies.

When Pope Francis summoned his ambitious Synods of Bishops on the Family in 2014-15, Grech surprised many observers by his welcoming and positive language on LGBTQ+ Catholics, in a talk which attracted favorable attention from the pontiff. There were rumors at the time that he might be named the Archbishop of Malta, but local Maltese media suggested a letter from some of his priests in Gozo complaining of an excessive attachment to material goods and poor government, including on an abuse case, scuttled his chances.

In 2017, Grech and Scicluna issued guidelines for Malta on the implementation of Francis’s post-synodal document Amoris Laetitia, which in a footnote opened a cautious door for the reception of communion by Catholics who divorce and remarry outside the church. At the timer some saw the Maltese guidelines as going even farther than the pope, although they were eventually published in L’Osservatore Romano, the Vatican newspaper, suggesting a sort of official endorsement.

By the time Grech was tapped to run the Synod of Bishops in 2019, he was considered a solidly pro-Francis figure in the global hierarchy. His administration of the two Synods on Synodality certainly burnished that reputation, giving him multiple occasions to extol the ideals of a more listening, participatory, and inclusive church.

In 2022 he also rejected an open letter from a group of more conservative Catholic bishops criticizing the progressive German “synodal way,” calling the statement “polarizing” and voicing confidence the Germans knew what they were doing.

What’s the case for Grech as pope?

To begin with, in a conclave in which so many cardinals are strangers to one another, he’s a known quantity. Of the 133 cardinals set to file into the Sistine Chapen next Wednesday, 62 of them took part in at least one of the two synods on synodality, meaning they’re used to seeing Grech sit in the front of the room and in charge. That in itself might be a selling point in a moment in which cardinals, feeling out of their depth, may be looking for someone to follow.

In addition, Grech would be seen as a vote for continuity with the Pope Francis agenda, but perhaps with slightly more legal precision and grounding given his deep background in church law. In other words, pro-Francis voters might see him as someone who could institutionalize the late pope’s legacy.

The case against?

First of all, the fact that he has changed so his tune so dramatically from the Benedict years in Gozo to the Francis years in Rome may be seen by some voters as evidence of an unreliable shifting with the wind, though others style it as an admirable capacity to change and grow with experience and circumstances. Certainly cardinals looking for assurances of greater doctrinal clarity probably would look askance.

Moreover, a vote for Grech is likely a vote for continuing a three-year synodal process that Pope Francis issued while he was in Rome’s Gemelli Hospital battling double pneumonia, which is designed to culminate in a grand “ecclesial assembly” with roughly equal numbers of bishops, priests and deacons, religious and lay people. Some conservative critics see the process as undermining the hierarchical nature of the church, but more broadly there’s simply a degree of “synod fatigue” among many prelates who may not be anxious to confirm yet another series of meetings on a theme many of them found amorphous and confusing.

Given there’s a general consensus that the next pope has to be a competent governor, among other things capable of tackling both the financial and the sexual abuse scandals that still haunt Catholicism, the concerns about Grech’s government style from his Gozo years probably don’t help his candidacy either.

Still, Grech has proven surprising capable over the years of adaptation and delivering surprises. Starting next Wednesday, we’ll see if he has one more surprise to spring.