ROME—On the night of October 11, 1962, thousands of people made their way to St. Peter’s Square to celebrate the beginning of the Second Vatican Council, called for by St. Pope John XXIII.

Unable to ignore the crowd, and before “off-the-cuff” remarks were simply what popes did, he improvised the most famous speech of his pontificate.

“My dear children, I hear your voices. Mine is just one, but it sums up the world’s. Here, the entire world is represented. I should say that even the moon has come out here tonight, to witness this amazing moment,” he said.

“Returning home, you will find your children. Give them a caress and tell them ‘This is the caress of the pope,’” said “the good pope,” as he was known, to the torch-lit cheers. “You will find some tears to dry, say a good word: the pope is with us, especially in times of sadness and bitterness.”

Francis, who has been an outspoken supporter of his predecessor — so much so that he declared him a saint by dispensing with the miracle requirement — recently borrowed almost exactly these words for a message that had a much sadder tone.

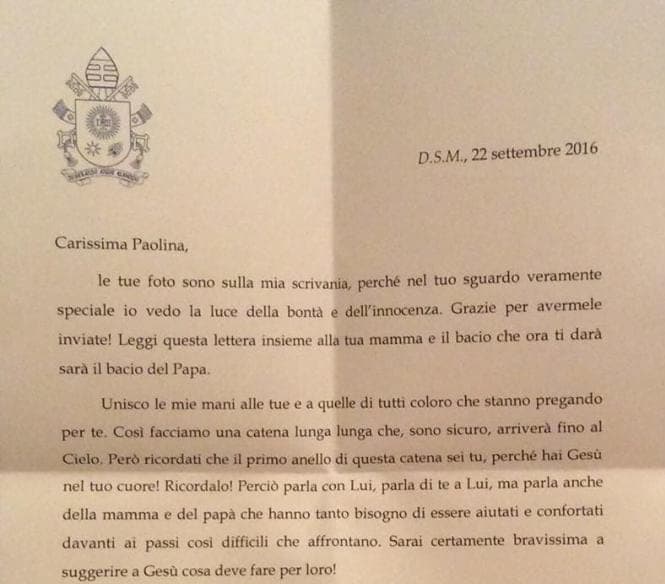

“Your pictures are now on my desk, because in your truly special eyes I see the light of kindness and innocence,” Francis wrote in a letter to a 9-year old, Paolina Libraro.

“Thank you for sending them to me! Read this letter together with your mother, and the kiss she will now give you will be the kiss of the pope.”

The pope’s letter, dated September 22, was accompanied with a VIP ticket to the Wednesday audience of October 26, where Francis presumably would have given Libraro a kiss himself. Yet she missed the appointment: she was already too weak, fighting a three-year long battle against cancer.

Libraro died Friday, November 22, the day the Catholic Church marks the feast of St. Cecilia, patroness of musicians, exactly six months after receiving her first Communion.

“When she died, she joined the choir of the saints, led by St. Cecilia,” her cousin, Giuseppe Delprete, told Crux.

“Young Paulina was lucid, and courageous, until the very end,” Delprete said. “She never cried, she was a lively, outgoing young girl who died fighting.”

Her strength was such that her cousin believes she didn’t die a girl, but an adult, fighting as if she were already one, more mature than she should have been at her young age, worried about bringing comfort and reassurances to her mother instead of focusing on her impending death.

“She lived such an intense and great life, that at the age of 10 she was called by God to go home,” her cousin said.

In his letter, Francis also tells Paulina that he’s united his hands to those of all who are praying for her, so that together they make a “long, long chain that, I’m sure, will reach up to heaven.”

Yet the pope doesn’t promise a miracle cure. On the contrary, the pope’s advice is for her to talk to God about her parents that have “a great need to be helped and comforted” during the difficult path ahead of them.

“You will certainly be really good in suggesting [to] Jesus what he needs to do for them!” he wrote.

The pope closes the letter asking Paulina to pray for him too, adding that he’ll pray for her and giving her “a strong, strong hug, and a blessing with all my heart.”

The letter was read at her funeral, held the day after her death, in a church with a standing-room only turnout. Among those present were Paulina’s friends, her family, and even the mayor of the small town, Massafra, in southeast Italy.

The local bishop, Claudio Maniago, was in Rome at the time, but the following day met with the family in private, so that he too could bring them comfort.

This is the second time Pope Francis has acknowledged putting something on his desk, as a reminder of something bigger.

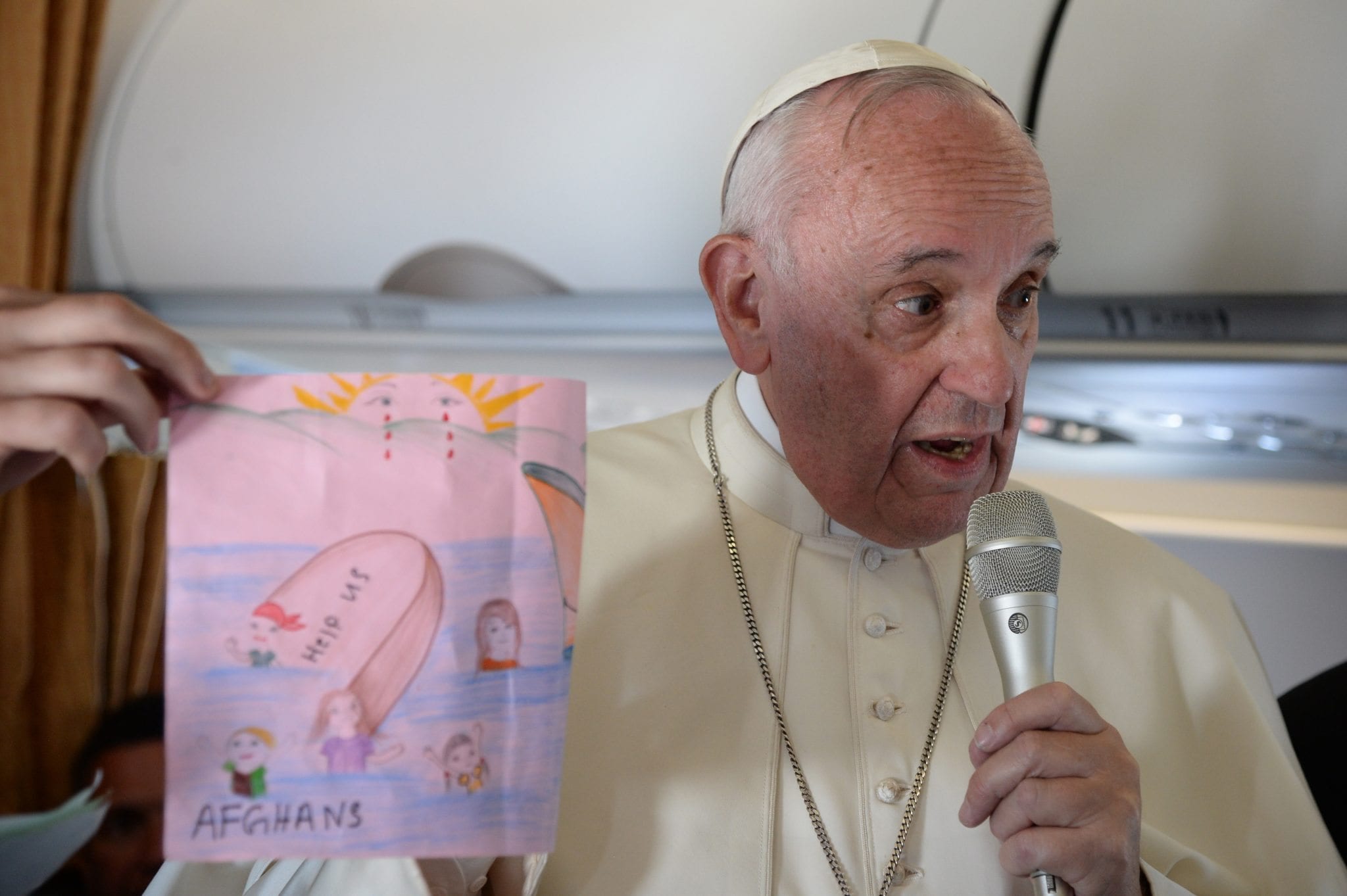

The first time he spoke about his work space was during his visit to the Greek island of Lesbos. Along that day-trip, he received dozens of drawings from refugee children showing their own stories.

One in particular, which depicted several people drowning under a sun shedding tears of blood, moved him so much that he decided to put it on his desk.

By Francis’s own admission, the picture is a reminder that there’s still kindness and innocence in the world. He didn’t put it in so many words, but it’s safe to say the eyes of the crying sun reminded him of the opposite.

On the way back from Greece, he told the journalists travelling with him about it: “After what I saw, what you saw, in that refugee camp, I felt like crying…What do children want? Peace, because they are suffering…My goodness the things that these children have seen! Look at this: they even saw a child drown. Children carry this in their hearts!

“These children have this impressed on their memories! And it will take time for them to process it. Look at this: one child drew a weeping sun. If the sun is able to cry then a tear or two would probably do us good.”

These are only two examples of many in which Francis reaches out to one person. Some have made headlines, like several of his famous phone calls that at one point were so common that a journalist saw it fit to write a “how to answer the phone if the pope calls” guide.

Some have remained private, as they were probably intended to be.

Whatever else Francis has become as universal pastor, he remains a parish priest, reaching out to help save one soul at a time.